"The Social Evil in Kansas City": Machine Politics and the Red-Light District

In a 1933 interview with journalist Jerome Beatty, Tom Pendergast cast himself as a protector of community values, boldly claiming that his political organization’s work had long been focused on stamping out any instance of vice or immorality in Kansas City: “We won’t have anything to do with helping drug peddlers or prostitutes. We put the whole strength of the organization to work to slug those people. And to slug them hard.”

The truth is, of course, much more complex than Pendergast made it out to be in 1933. Pendergast did not, in fact, “slug” drug dealers or sex workers. On the contrary, he profited from them. By that time it was widely known in Kansas City that “Boss” Tom Pendergast had amassed a fortune and considerable political influence through illicit means. Trading in liquor, drugs, gambling, and women, Pendergast profited immensely from the wide-open character of turn-of-the-century Kansas City. Though he also made money through more socially acceptable means (like the construction contracts he fulfilled through his own Ready Mixed Concrete Company), Pendergast did not discriminate when it came to turning a profit.

Consequently, the impact Pendergast had on the social, political, and financial development of Kansas City cannot be overstated. For it was not simply that the wide-open nature of the town existed and Pendergast profited from it; he also contributed to its creation and maintenance over the course of his many years as the de facto political boss of Kansas City. And while official histories of Kansas City may tend to focus more on the development of socially palatable industries like rail and agriculture, it cannot be denied that all manner of vice—especially the liquor and commercialized sex industries—contributed just as much to the growth and development of this midwestern metropolis.

Location, Location, Location

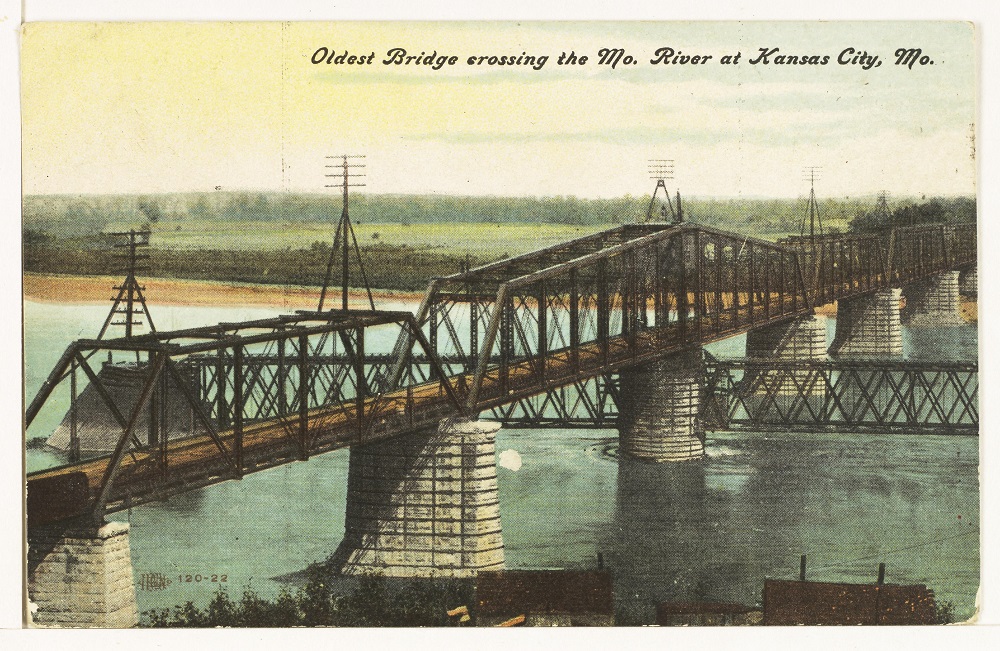

Kansas City was uniquely positioned to become an important center of industry in the Midwest at the turn of the 20th century. Rapid growth in the region was made possible by the opening of the Hannibal Bridge in 1869. This bridge was the first in the United States to cross the Missouri River and provided rail transport to cities all throughout the western and southwestern portions of the country. This, in turn, made Kansas City an important gateway to the west for people and goods traveling from the East. Consequently, industry flourished and the population swelled.

And yet, even as Kansas City was on its way to becoming a more modern, industrialized place, it was still very much a western frontier town. Writing of the years just after the opening of the Hannibal Bridge, author J. Michael Cronan describes Kansas City in the following way:

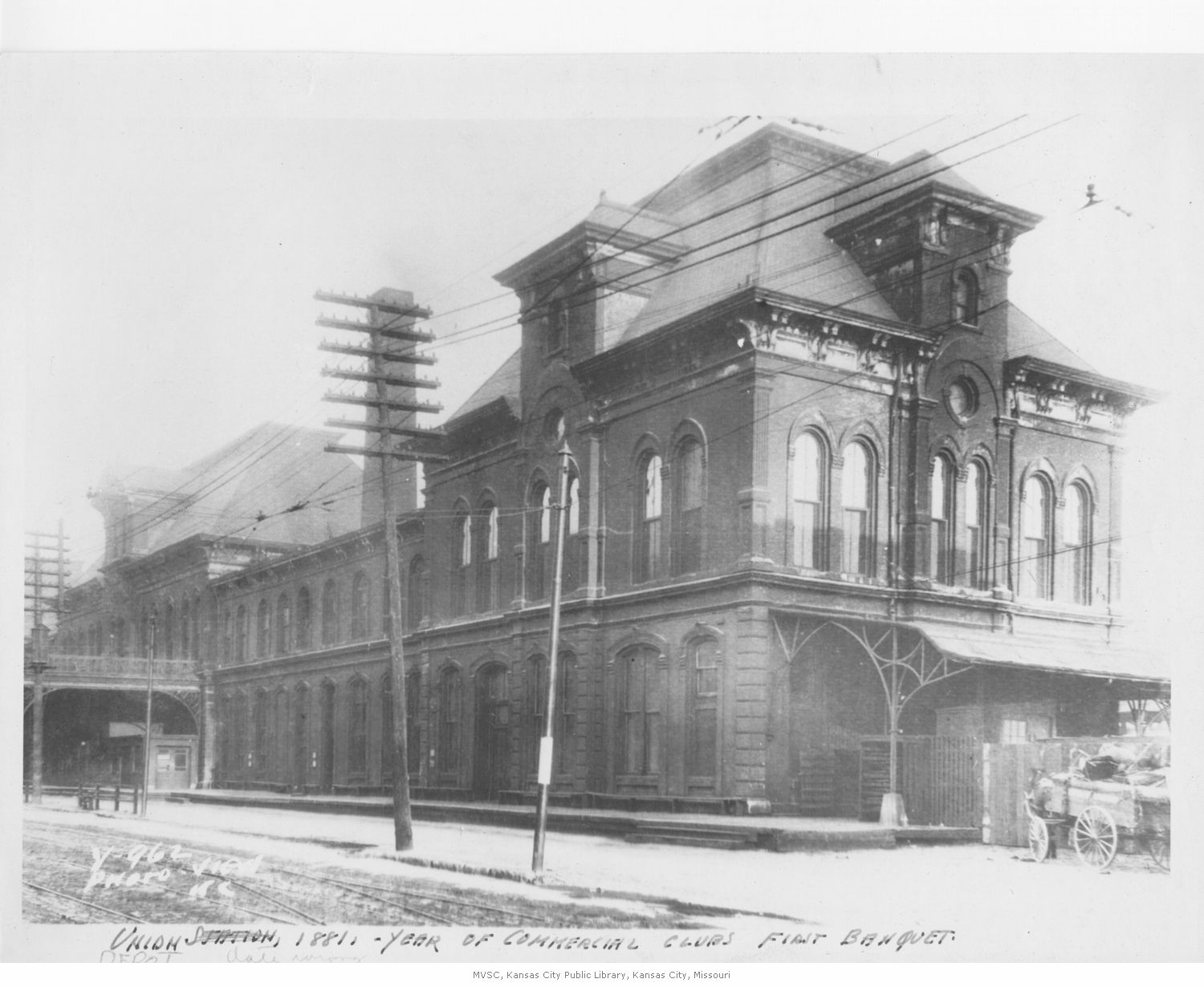

Upon arrival [to Kansas City’s Union Station], detraining passengers were confronted with the overpowering stench from the stockyards and slaughterhouses. Then, after leaving the station, they likely were required to maneuver around delivery wagons hauling kegs of beer and freshly slaughtered carcasses. In places, the dirt streets of the city were occupied by roaming pigs and mule drawn street cars...The municipal water system was described as that which made whisky-drinking a virtue.

This mix of rapidly growing industry and western frontier sensibilities made for an environment that could be rough, at times, and was open in more ways than one. The growth of industry meant that a variety of people from all over the United States and beyond traveled to Kansas City in search of work. Some travelers made Kansas City their permanent home while others merely passed through on their journeys farther west. In either case, this flux of people into and out of the city led to the rise of another vitally important industry in the development of Kansas City: vice. The steady stream of travelers, often men, created high demand for a particular kind of recreation. Gambling, drinking, and prostitution—a veritable trifecta of vice—developed in the saloons and bawdy houses surrounding the old Union Depot, in the West Bottoms area, to meet this demand. Put another way, Cronan suggests that “the mixture of commerce by cowboys, steamboats, and railroads presented an environment where there were more than twice as many gaming houses and saloons as there were churches” in 1880s Kansas City.

As time wore on and such entertainments proliferated, Kansas City developed a reputation as a “wide-open town.” Although existing law did define and forbid lewd behavior and commercialized sex (City Ordinance No. 291 had been on the books since 1880), it was rarely enforced by city authorities. In Queering Kansas City Jazz, historian Amber R. Clifford-Napoleone writes that “numerous clubs, theaters, saloons, and brothels in Kansas City violated Ordinance No. 291. Kansas City’s civic leaders declined to close every saloon and brothel in town lest they offend workers and visiting businessmen. It seemed that Kansas City’s economic success was largely supported by sex tourism in the city’s red-light district and jazz spaces.” It was an understood and accepted fact of life in Kansas City that these illicit trades coexisted alongside licit ones.

One of the primary reasons vice was able to flourish in Kansas City was the careful cordoning off of the red-light district from the rest of the town. For many years, brothels and other houses of ill fame operated openly, enclosed within the First and Second Wards of the River Market neighborhood. Brothels, where madams and prostitutes lived and worked full time, lined each side of 3rd and 4th Streets for blocks; saloon owners in the area also operated “assignation houses” with upstairs rooms available for rent by the hour. These houses accommodated sex workers who did not live in a brothel but came to the district for work nonetheless. Not only did the separateness of the red-light district make it rather simple for customers to seek out commercialized sex, this separation also ensured some measure of safety and security (for all parties involved) from zealous reformers who called on police and city government to enforce City Ordinance No. 291.

Because the red-light district in Kansas City was segregated from the rest of the goings on in town, most citizens were content to ignore it. Though there were certainly those who advocated for the elimination of prostitution altogether, many other Kansas Citians were happy to attend to other, more pressing civic matters first. Indeed, in a chapter dedicated to exploring the history of Kansas City’s red-light district, Clifford-Napoleone asks, “why did Kansas City reformers not try to simply eradicate prostitution? In addition to the moral zoning thought to defend ‘respectable’ native-born white women, the enclosure of the red-light district led reformers to deal with other ‘problems’ as a more immediate threat.” This creation of a separate space where madams, sex workers, and saloon owners could all ply their trades in relative safety meant that vice could flourish there. But as the city continued to expand and grow southward, so too did its red-light district.

In a 1911 report colorfully titled “The Social Evil in Kansas City,” Board of Public Welfare Superintendent Fred R. Johnson explained that what was once a relatively confined district had spread southward throughout the city: “Two centers of the red-light district, with no well defined limits, are found in the city. One is in the North End, and the other on the South Side. Some of the most notorious dives of both sections are found on the main thoroughfares of the city. This is particularly true of the South Side, with a number of the worst resorts of the municipality existing on Main Street with its numerous car lines.”

In much the same way that the expansion of the railroad initially helped establish Kansas City as a center of vice, so too did the expansion of publicly available transit in town facilitate the spread of commercial sex. And as brothels, bawdy houses, and saloons continued to proliferate throughout the city, increasing numbers of women entered the profession. While it was certainly a challenging life in many ways, prostitution also offered many women shelter from destitution and even a degree of financial freedom and social autonomy that they would not have been able to access otherwise.

Life Along the Primrose Path

Many of the young women who entered the trade in these years did so because they had few opportunities for employment open to them that could actually sustain their lives. If they could not rely on the support of a family or husband, these women were left to devise some other plan for their survival. Johnson’s 1911 report indicated that low wages was one of the most common reasons why a woman entered this line of work. He wrote that of the 300 women he and his team interviewed, a full “51% received less than $6.00 per week” in wages. Calling prostitution a “disease of poverty,” Johnson elaborated:

It has been conclusively proved that $7.00 per week is the lowest to afford decent subsistence for a woman. Some authorities would place this at $9.00. It has also been conclusively proved, and necessarily follows, that industries paying not more than $4.00, $5.00 or even $6.00 per week to competent women employees are in reality parasitic and a grave menace to the American home.

Though he did not indicate how such points were “conclusively proved,” Johnson highlighted an important issue here. Despite the widespread belief during this time that any woman who embarked upon such a career must necessarily be morally deficient, Johnson made clear that poverty was quite often the largest motivating factor. Considering that a woman “in the life” could expect to earn $25.00 per week on average, according to Johnson’s figures, it is no wonder that many women who entered this profession often remained in it.

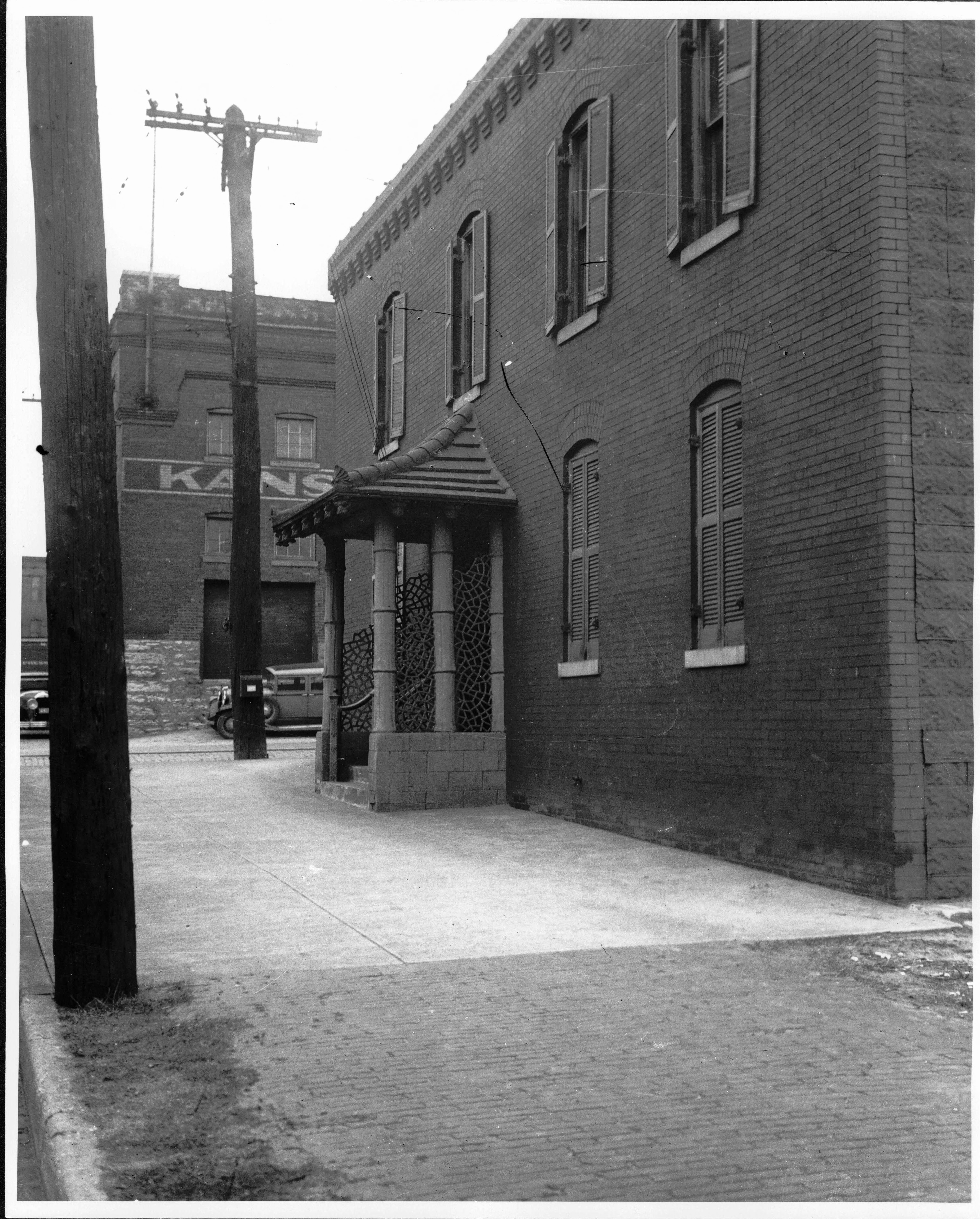

Indeed, one such woman who followed this path would eventually go on to become Kansas City’s most famous madam; no discussion of prostitution in Kansas City is complete without mention of Annie Chambers. Leaving a life of tragedy and heartbreak behind in her home state of Kentucky, Chambers moved to Indianapolis, where she began to work as a prostitute. After being arrested several times and finding the climate there inhospitable to her line of work, Chambers moved to Kansas City in 1870 on the advice of a friend and in the hopes that her trade would be better tolerated there. This second move proved auspicious for Chambers, and she soon opened a small brothel just north of the Missouri River. Just two short years later, Chambers had amassed enough wealth to open a lavish 25-room brothel south of the river on the corner of 3rd and Wyandotte Streets, where she remained for many years. With a tiled entry way bearing her name, opulent draperies, and a famed 5 by 11 foot nude painting hung in the hall, Chambers’s brothel gained a reputation as one of the finest “resorts” (as brothels were commonly called then) in Kansas City. At a time when the average price for services at a brothel was $1.50, Chambers’s girls regularly charged clientele as much as $10.00. Under the standard operating rule in which the madam received half, it is easy to see how this business became quite profitable for Chambers.

Annie Chambers was far from the only madam operating in Kansas City, however. Clifford-Napoleone notes that “there were 128 brothels listed on Kansas City police fine lists in 1910 alone” alongside 147 “assignation houses,” not to mention the numerous other saloons and bawdy houses absent from these official lists. Other popular and busy resorts in the red-light district were just down the street from Chambers. These belonged to Madame Lovejoy and Eva Prince. In 1934, one reporter for the Kansas City Star called these three houses of ill fame “the three most notorious houses of the kind in the ‘red-light district,’” and even referred to these powerful madams as “the queens of the red light.”

Women like Chambers, Lovejoy, and Prince were able to attain such power and wealth thanks in large part to the lax stance Kansas City police and local government took toward prostitution. Though these madams were officially fined each month for violating Ordinance 291, their payments operated functionally more like a licensing system than as a deterrent. Indeed, Johnson summarized in his 1911 report:

No settled policy either of suppression or of segregation of the Social Evil has been adopted by Kansas City. Ordinances on the subject conflict. Some of them would recognize the scourge while others would eliminate it. Meanwhile it has enjoyed a semi-legal standing. The keepers of resorts are each month brought into court and ‘fined’ for plying their trade. The ‘fine’ is considered as more or less of a joke by the proprietors and virtually amounts to a license.

This “semi-legal standing” meant that those in the trade could conduct their business in relative safety. Madams at some of the better houses (like Chambers, Lovejoy, and Prince) became quite wealthy as a result. Johnson estimated that the average brothel housed four prostitutes, bringing the average madam’s weekly profits to just under $100.00. Considering that Chambers’s spacious resort contained 25 rooms, it is safe to assume her weekly earnings were considerably larger than $100.00. It is then quite easy to see how a madam like Chambers would happily pay monthly fines in order to keep her business operating.

A Firsthand Account: Madeleine’s Story

Top down: Flo Beach, Mollie Mantel, Mary Hunter, Miss Helen Spencer, Louise Woolard

Such a relationship between the madams and local authorities also meant that the women working in the brothels could largely be assured that they would not run afoul of the law. Although firsthand accounts of young women working in the trade are rare, an autobiography published in 1919 sheds some light on what life was like for sex workers in the Midwest at this time. Madeleine, an Autobiography is one of the few memoirs of its kind whose details were later substantiated by historians. The protagonist, Madeleine, was a young woman who faced considerable hardship at a very young age. Her father became alcoholic and abusive when she was still a child, and their large family was forced into severe poverty as a result. She endured years of privation and abuse before her mother sent her away to live and work with a friend in St. Louis. Finding her health failing from hard work in a factory and barely able to sustain herself on the meager wages she earned there, Madeleine then learned that she had become pregnant from “a moment’s sin” engaged in just before leaving her hometown. Ashamed and unsure of what she should do, Madeleine determines to leave St. Louis to “bear [her] disgrace alone.”

This turn of events is what ultimately brings Madeleine to Kansas City. Having tried in vain to find any other suitable position in St. Louis, Madeleine runs out of money and turns to prostitution in order to survive. Writing of the difficulty of this choice, Madeleine asserts: “I, an attractive young girl, homeless, defenseless, hungry, and in a few months to become a mother, had no choice between the course I took and the Mississippi River.” After several frightening encounters with rough men in St. Louis, Madeleine meets a wealthy man who takes pity on her and treats her quite well in comparison. Being called away to Kansas City on business, this man takes Madeleine with him. There she becomes ill, having contracted some form of venereal disease from him, and remains in Kansas City to convalesce after her companion’s return to St. Louis. It is at this point in Madeleine’s narrative that readers begin to see a more detailed picture of what life was like in Kansas City’s red-light district.

Madeleine makes a fateful connection while she is convalescing. The woman with whom she shares a hospital room—Mamie—happens to work at Madam Lovejoy’s brothel on West 4th Street. Mamie, who is convalescing for the same reason Madeleine is, relates all of the ways a young woman can benefit from working in one of the city’s finer resorts. She tells Madeleine “that a girl who got into the right kind of a house had good food, a beautiful room, and was cared for if she got sick; she was not preyed upon by the class of men who wanted something for which they were not willing to pay. She was protected by the police, and, what was still more important, she was protected from the police.” Intrigued by Mamie’s words and out of other options, Madeleine goes to see Madam Lovejoy.

The madam, or Miss Laura, as Madeleine calls her, is a warm, kind, and maternal figure. She is sympathetic to Madeleine’s situation and offers to take her in. Though Madeleine was not entirely new to the world of prostitution, she writes that “the process of education in the oldest profession in the world is like any other educational process, in that it requires time and effort and patience; it can only be acquired by taking one step at a time, though the steps become accelerated after the first few.” For example, Madeleine needed some coaching to understand that a brothel’s primary source of income was the sale of liquor, and that the women who lived there were meant to help facilitate those sales.

She also had to learn that clients were often just as interested in knowing her life and history as they were in knowing her body. Initially outraged at this demand on her private life, she had to work to develop a certain level of comfort with sharing her personal history. Madeleine credits Madam Lovejoy with giving her the education she would need to survive along “the primrose path.” While living and working at Madam Lovejoy’s, Madeleine learned how to practice her trade skillfully and earned more than enough money to live comfortably and independently in Kansas City.

In the narrative, Madeleine also goes out of her way to dispense with several stereotypical notions of what it meant to live and work as a prostitute. Upon first meeting Miss Laura, Madeleine explains that the woman who greeted her was nothing like the “horrible creature” of her imagination. Where she expected to find a vile and ruthless madam, Madeleine found instead a soft-spoken and large-hearted woman whose primary interest was the safety and wellbeing of the girls working in her home. In addition to providing a bountiful table and comfortable furnishings, Miss Laura never took more than her share of half the cost of services, even though it was common practice in other resorts for a madam to lay claim to any sort of tip a client might leave to a woman. Madeleine also relates that her colleagues in the house were equally kind and helpful to her. Upon learning that Madeleine was with child, all the rest of the residents of the house set about preparing clothes and toys in preparation for the coming baby.

Madeleine credits the supportive atmosphere at Miss Laura’s to the kindness of its owner. She explains, “every business of this kind reflects, to a large degree, the personality of the keeper, and the spirit of the house is largely the spirit of the woman who presides over it. Because this woman was broad-gaged and kindly, there was a spirit of tolerance and fellowship in her establishment such as I have seldom seen elsewhere.” Though some parts of Madeleine’s story do tend to confirm stereotypes about women “in the life,” at other junctures she is quite clear about the ways many of these stereotypes are incorrect.

In her reflections about life in red-light Kansas City generally, Madeleine offers readers insight into the social climate of the era. Explaining that the “moral conditions” in Kansas City were rather poor during her time there, Madeleine elaborates:

The restricted district extended for several blocks on Third and Fourth Streets, but segregation was a name only, not a fact.

Vice flourished in all parts of the city, but especially in the rooming-house districts; wine-rooms were wide open for any one having the price of a drink; private houses and assignation-houses abounded throughout the residential parts of the city; and the roadhouses ran full blast for twenty-four hours a day. . . .

There were three first-class places, of which Miss Laura’s was one. That is, these houses maintained a high price, regardless of the condition of business or of the keenness of competition, and they harbored a better class of women.

Descriptions like this one throw into sharp relief both the size and the significance of this industry in Kansas City. One of the primary reasons commercialized sex was able to thrive in Kansas City was the mutually beneficial relationship it enjoyed with the Pendergast political machine.

Prostitution and the Pendergast Machine

Tom Pendergast has long been connected with the industries of vice in Kansas City. Indeed, the Pendergast family first gained prominence and influence in Kansas City when Tom’s older brother, James Francis Pendergast, opened a saloon and hotel in the West Bottoms neighborhood in the 1880s. From these roots the entire Pendergast political machine would evolve. When Tom took control after his brother’s death in 1911, his financial prosperity grew in direct proportion with the open practice and tolerance of vice in Kansas City. In addition to a well-known penchant for gambling, Pendergast also owned and operated the T.J. Pendergast Wholesale Liquor Co. (sensibly renamed Pendergast Distributing Co. during the years of Prohibition). A significant amount of his profits also came from “houses of ill fame.”

This should come as no surprise since the red-light district in Kansas City was for many years intentionally sequestered as a separate zone enclosed in the First and Second Wards. This area was Pendergast territory, encompassing the West Bottoms and representing the original seat of power in the Pendergast machine. Historian Clifford-Napoleone asserts that “as part of the Pendergast world sex tourism was a constant source of income, business, and patronage for Pendergast, his machine, and the city of Kansas City.” The protections those in the red-light district received from city police officers were due in large part to the fact that many of those same officers owed their jobs to Boss Tom. Clifford-Napoleone makes the connection between the various forms of vice exploited by the Pendergast machine and police corruption quite clear:

Pendergast had interests in prostitution and saloons in a manner similar to that of systems in other cities. For instance Pendergast owned at least two hotels where the availability of prostitution was an open secret. Pendergast simply paid a cut of the prostitution income payments to the city police.

One of the Pendergast-owned hotels referenced above was the Jefferson Hotel on West 6th Street. It was widely known that the upper floors of the Jefferson operated as an assignation house, where street-level sex workers and their clientele could rent rooms by the hour. Anti-vice crusaders in Kansas City also claimed that a full-scale brothel operated on the lower floors, and that the entire 5th floor had been sealed off for private poker games. Perhaps most notable at the Jefferson, though, was the nightly activity in its basement. In 1947, former Kansas City Star journalist William M. Reddig wrote of the Jefferson that “it acquired more than local notoriety after the . . . boss made it the headquarters for politicians and convivial citizens who never wanted to go home. The hotel’s chief charm was the cabaret in its basement. There was nothing quite like the Jefferson celebration anywhere else.” Cabarets became wildly popular in Kansas City during Pendergast’s reign, so it seems only natural that Boss Tom found a way to make a bit of money from them.

Historian Lawrence H. Larsen and author Nancy J. Hulston also elaborate on Pendergast’s connection to the notorious Chesterfield Club. Located just one block from the federal courthouse downtown, Larsen and Hulston write that the Chesterfield was a “famous Pendergast sin place,” one that seemed a “deliberate affront to conventional morality.” Indeed, the goings on at the Chesterfield seem particularly over the top when compared to other places in town. Trumpeted as a swanky supper club, this establishment was notorious for the wild antics permitted inside. It was not at all uncommon to see Kansas City’s elite businessmen inside for lunch, being served by nude waitresses wearing nothing but “shoes and a change belt.” These same waitresses were famed for being able to pick a tip up from their tables without using their hands. Local madams would bring their girls in to waitress for the day, with many ultimately finding themselves on the upper floors with Chesterfield patrons. Pendergast was a fixture at the Chesterfield and known to conduct much of his business there. Larsen and Hulston write that he even went so far as to host weekly parties there for those loyal to him: “On Friday afternoons, the Pendergast machine held regularly scheduled ribald sex parties featuring nude dancing and backroom sex at the Chesterfield as a reward for male precinct workers and others.” With access to gambling if they so desired, drinking liquor supplied by T.J. Pendergast Wholesale Liquor, and in the company of sex workers protected by Pendergast’s hand-picked police force, revelers at the Chesterfield truly indulged in the wide-open world of “Tom’s town.”

All of this amounted to rather big business for Pendergast. Fred R. Johnson, author of “The Social Evil in Kansas City,” estimated the total amount spent on prostitution over a one-year period in Kansas City. Based on the 554 sex workers involved in his department’s study, with a population of 248,000 in Kansas City in 1910, Johnson calculates total expenditures to be “$1,425,580.50 annually.” Translated into comparable figures today, this would amount roughly to $38 million! Johnson also carefully noted that his calculations were likely an undercount. “These figures,” he wrote, “startling as they are, represent but a fraction of the sums spent on prostitution in Kansas City. They include only the outlay in houses of ill fame found on the police fine list. We may but conjecture the amount expended in questionable rooming houses, upon street solicitors, and upon the numerous forms of clandestine prostitution which exist in the city.” Larsen and Hulston estimate that in his own day, “Pendergast’s take reportedly was $20 million annually from gambling, with another $12 million from prostitution and narcotics.”

In a city whose fortunes were for decades so tightly bound up with those of one very powerful and corrupt man, it becomes impossible to separate the success of one from the financial prosperity, however illicitly gained, of the other. In other words, the cultural and political environment in Kansas City that proved so conducive to the rise of industries like the railways and stockyards is the very same one that led to the flourishing of all manner of vice in the very same place. So when we reflect on the industries, systems, and individuals responsible for the growth and development of Kansas City during the Pendergast years, we would do well to remember that a significant portion of that success was due to a class of laborers so often written out of official histories and progress narratives. Without vice industries in general, and commercialized sex work specifically, Kansas City would not have been the thriving “wide-open” town it was in the earliest decades of the 20th century.

This essay was developed as part of an Applied Humanities Summer Fellowship, cosponsored by the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.