Radio Pioneers: The Coon-Sanders Nighthawks

When Coon and Sanders start to play,

Those Nighthawk Blues you’ll start to sway,

Tune right in on the radio, grab a telegram and say hello

--Nighthawk Blues

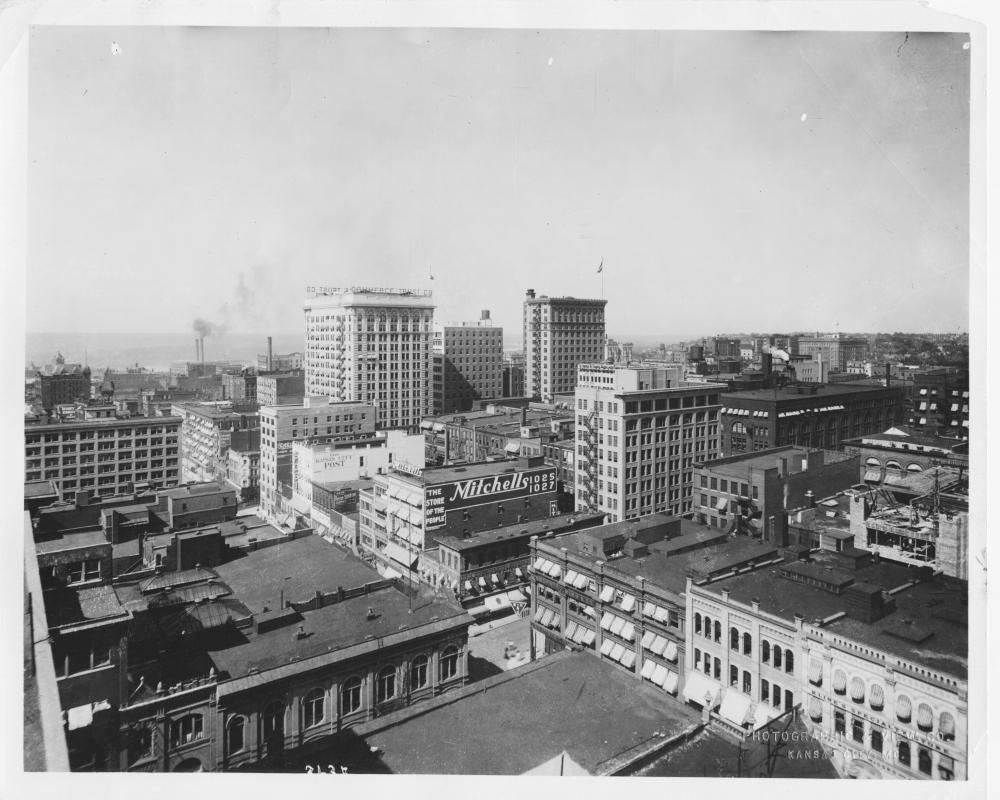

Jazz was born in New Orleans, moved to Chicago in the early 1920s, and came of age in New York and Kansas City during the 1930s and 1940s. Geographically isolated from the other cradles of jazz, Kansas City bred a distinctive hard swinging style of jazz, distinguished by driving rhythm sections and a spirited call and response interplay between the instrumental soloists and the brass and reed sections.

As Bennie Moten, George E. Lee, and other African American bandleaders based at 18th and Vine pioneered a new style of jazz, a number of white bands in downtown Kansas City were performing a style of hot jazz modeled after nationally popular white bands. Ironically, while Kansas City would gain renown for its great African American bands that barnstormed across country, it was a white dance band, the Coon-Sanders Nighthawk Orchestra, which first established Kansas City’s national reputation as a jazz center.

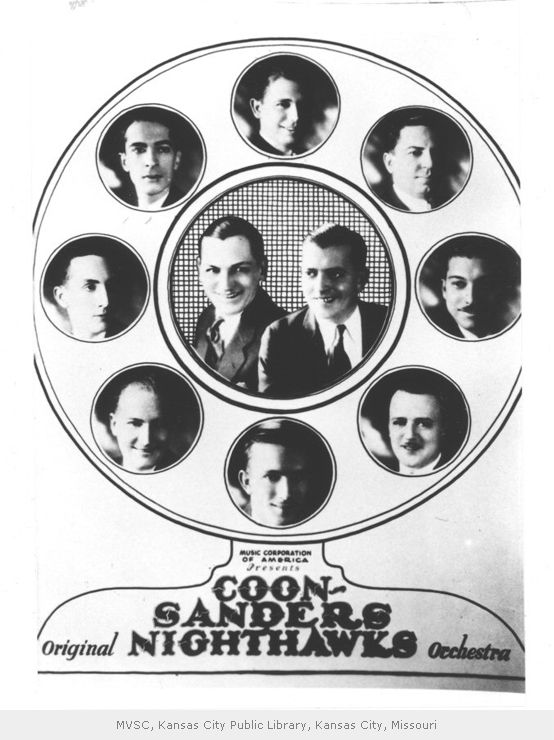

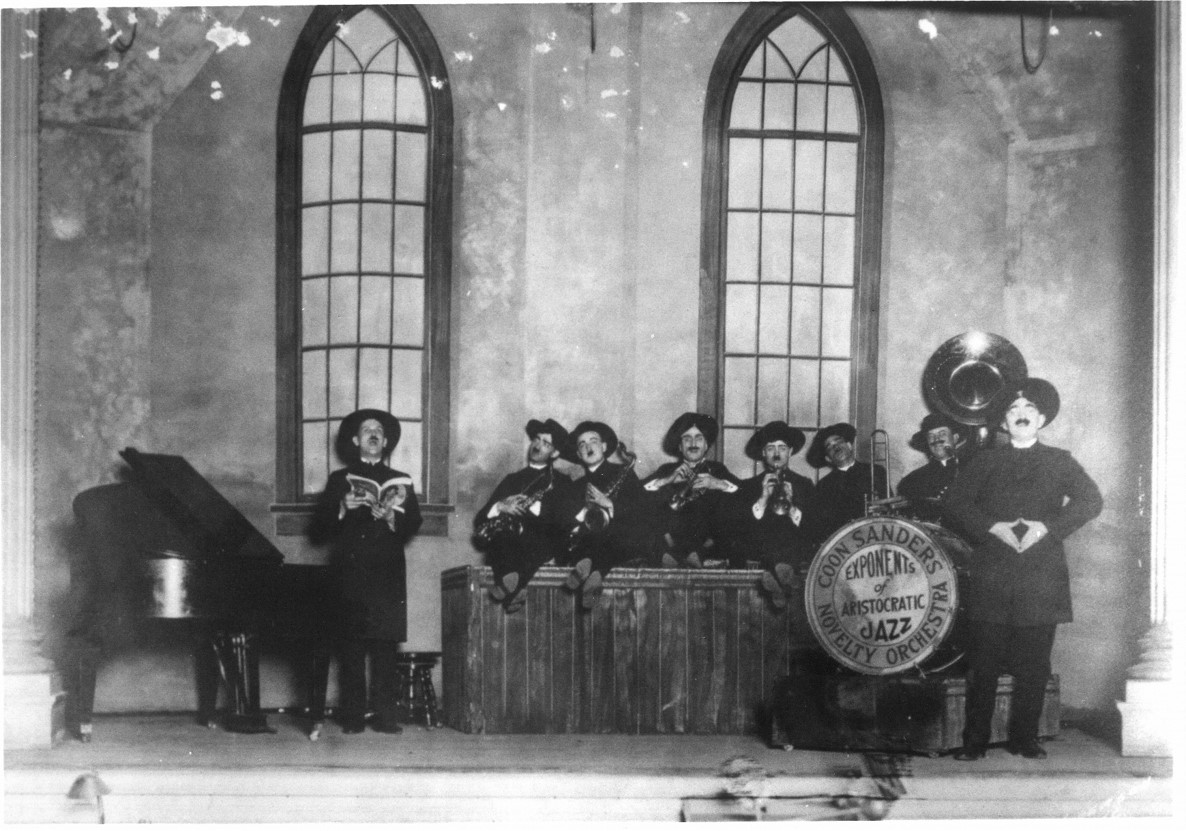

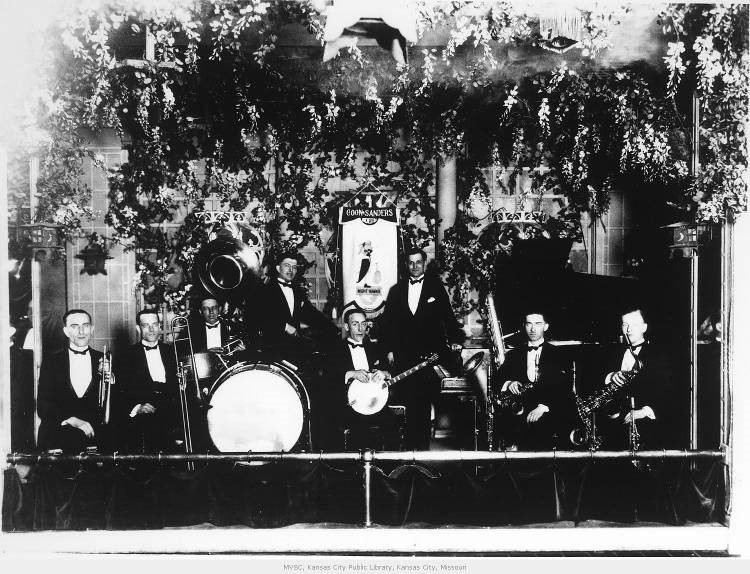

The Coon-Sanders Nighthawk Orchestra was the most successful and influential of the early white bands to come out of Kansas City. Co-led by drummer Carleton Coon and pianist Joe Sanders, the Nighthawks performed novelty tunes, popular songs, and hot jazz, which featured close vocal harmonies, syncopation, instrumental solos, and spread voicing of the three-member saxophone section. During the 1920s, the Nighthawks’ popularity eclipsed the bands of Jean Goldkette and Ben Bernie, and rivaled the "King of Jazz," Paul Whiteman.

In 1922, the Nighthawks’ late night radio broadcasts—a new phenomenon at the time—from Kansas City over WDAF created a national sensation. In 1896, Guglielmo Marconi patented the technology to transmit radio waves over great distances. In the early 1920s, the technology to broadcast human voice and music using radio waves became widely available. In 1920, KDKA in East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, became the first radio station licensed by the government. In January 1922, there were still just four licensed radio stations operating in the United States, but within a year, this number leaped to 576 as the new media became a national craze.

Located in the “Heart of America,” WDAF’s signal could be picked up across the continent. Thousands of listeners tuned in to the Nighthawk’s nightly broadcasts, making Kansas City a beacon of jazz. Throughout their careers, Coon and Sanders continued to pioneer trends in radio broadcasting, including becoming one of the first organized bands to broadcast nationally and the first to establish a radio fan club. The Nighthawks’ broadcasts were so popular during the 1920s and early 1930s that they became known as the “band that made radio famous.”

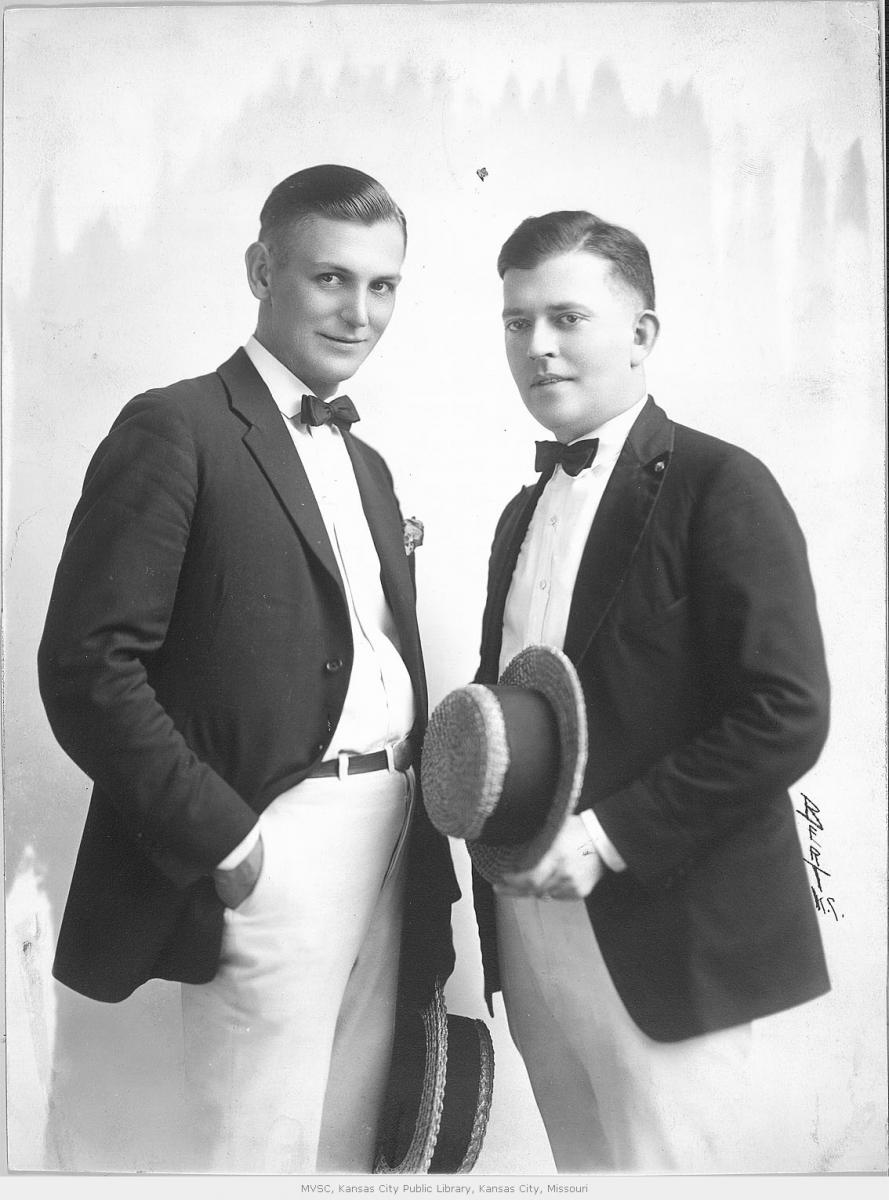

Origins of the Coon-Sanders Partnership

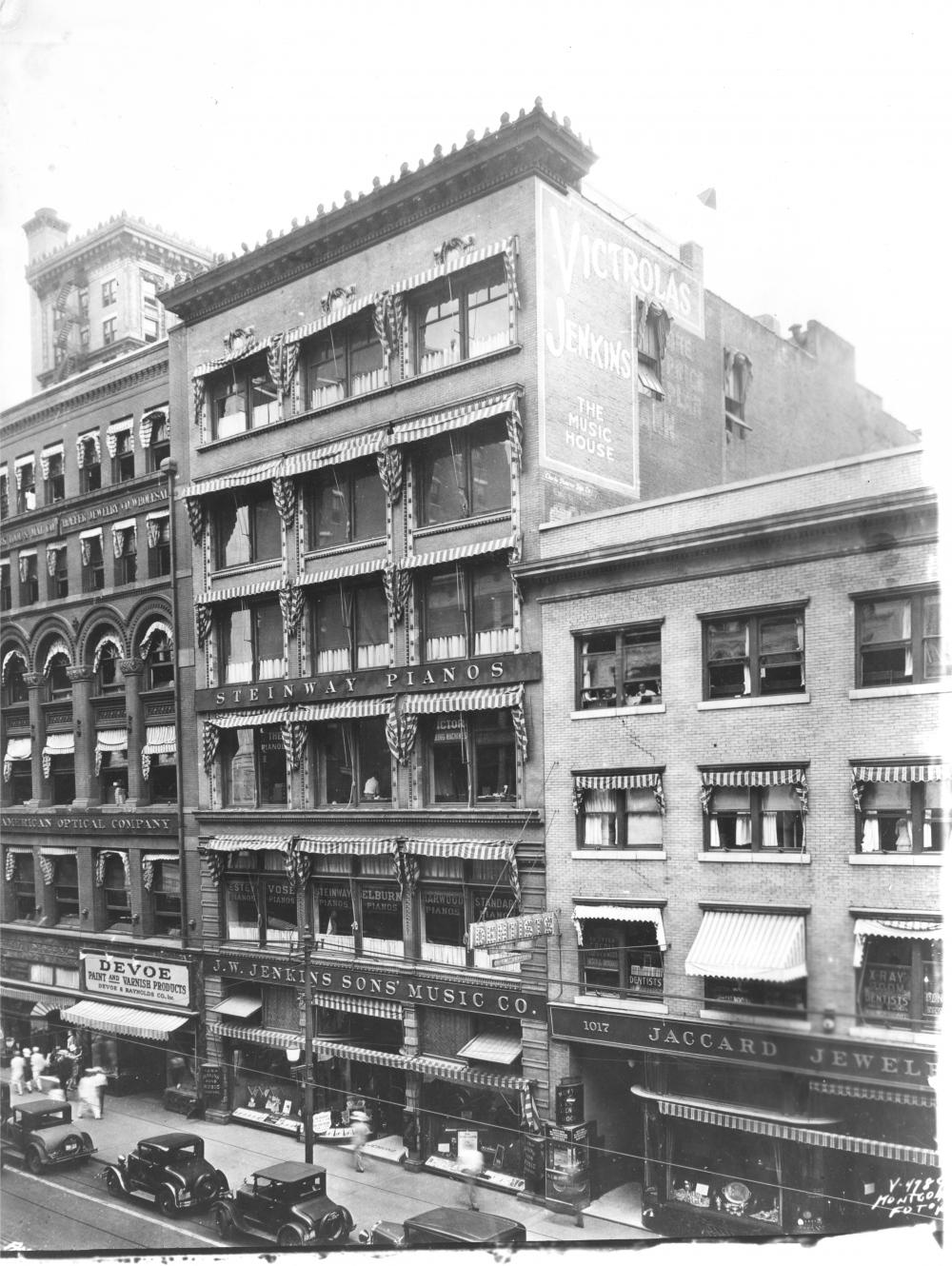

Coon and Sanders’s wildly successful association began just a few years earlier with a fortuitous encounter. They met in 1918 at the J.W. Jenkins Music store in downtown Kansas City. According to Sanders, he was playing the piano and humming softly while auditioning some new sheet music when, “I suddenly heard a voice join me. A lovely tenor quality proved to be possessed by Carleton A. Coon...” Striking up a friendship, Coon and Sanders began performing around town as a vocal duo and with small bands.

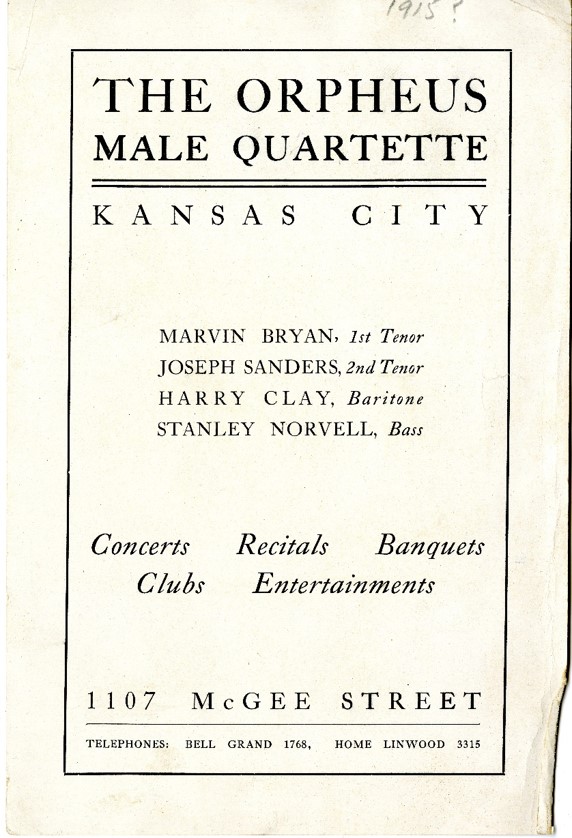

Sanders, who had performed as a classical vocalist and pianist for numerous churches and civic events around town since he was a youth, was well known to Kansas City music fans. Blessed with an ear for a catchy phrase, Sanders also composed popular songs. At the time, Coon’s career was also on the rise. He started by performing with vocal groups for social events and fundraisers on the Kansas side of the metropolitan area. Although just two years older than Sanders and less accomplished musically, Coon assumed the role of senior partner.

On October 3, 1918, Coon and Sanders entertained a crowd of 13,000 attending a war bond rally led by former President Theodore Roosevelt at Convention Hall. They performed “Kick In,” a song composed by Sanders for the campaign. The Kansas City Star reported, “Joseph L. Saunders [sic] and Carleton Coon entertained the waiting audience with singing patriotic songs, including ‘Kick In,’ one of the fourth Liberty Loan songs. The lilt of the tune and parts of the words were learned by the crowd, all joining in to help make the hall resound to the song of encouragement to ‘Buy! Buy! Buy!” Following the sing-along led by Coon and Sanders, Roosevelt bounded on stage to address the roaring crowd. Roosevelt became the first of a string of luminaries with whom Coon and Sanders would rub shoulders during their careers. Shortly after the war bond rally, Sanders was drafted, ending his initial association with Coon.

After the war, however, Coon and Sanders reunited and formed a band that became one of the most popular dance bands of the 1920s. Their lives and music personified the exuberance and excesses of America during the 1920s, a decade that came to be known as the Jazz Age. Like Nick Carraway (F. Scott Fitzgerald’s narrator for The Great Gatsby), Coon and Sanders grew up in the Midwest and moved to New York, where they enjoyed fame and experienced tragedy.

Carleton Allyn Coon, who was affectionately known as "Coonie," was gregarious and happy-go-lucky. He was born in Rochester, Minnesota, on February 5, 1894. His mother abandoned the family when he was a child. In 1898, Coon and his father moved to Lexington, Missouri, an historic Civil War-era town nestled on the bluffs above the Missouri River. His father owned a hotel and sold Allen’s Red Tame Cherry, a popular soda fountain syrup. A philanderer, Coon’s father insisted that Coon refer to him in public as uncle.

With little adult supervision, Coon spent considerable time hanging out on the docks on the Missouri River with stevedores and warehouse workers, picking up “bits and snatches of folk music and spirituals from black workers,” as described in the Kansas City Star in 1989. With their encouragement, Coon began playing bones, which soon led to the drums. Coon also was influenced by the drummers in the military bands at nearby Wentworth Military Academy.

When Coon was a teen, he moved with his father to Kansas City, Kansas, where he attended high school. During the evenings, he learned to entertain while leading the sing-along at the Electric Theater. After graduating from high school, Coon worked as a chief milk inspector for Kansas City, Kansas. Coon took his job seriously and publicly crusaded to assure that the milk supply was safe. He learned harmony and melody while performing with vocal quartets for social groups and civic functions.

Joe Sanders

Tall, handsome and athletic, Joseph LaCeil Sanders was a gifted pianist, composer, and arranger. Sanders was born on October 15, 1896, in his grandmother’s hotel in Thayer, Kansas. He later mused that it “seems odd that I was born in a country hotel and have spent most of my life living and playing in hotels.” The family moved frequently on the whims of the father, a hard-luck cattleman, land speculator, and oil man.

When Sanders was five, his family moved to Belton, Missouri, located southeast of Kansas City, where his parents operated a hotel. A child prodigy, Sanders studied piano and voice. Sanders began his musical career as a boy soprano at the Grand Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church, a prosperous congregation located at 205 East 9th Street in downtown Kansas City. He became celebrated for his vocal range, spanning two and a half octaves, and for his virtuosity at the piano.

In 1913, the Sanders family moved to Kansas City, where Joe attended Westport High School his senior year. At night, Sanders accompanied female cabaret singers at the Blue Goose Café, a popular nightclub located in the lower level of the Hotel White at 9th and Wyandotte. At the time, downtown Kansas City sported many cabarets, saloons, taverns, and bars that featured live music, ranging from ragtime to pop songs of the day. Kansas City’s other leading cabaret, the Jefferson Café, was located in the basement of the Jefferson Hotel, the headquarters for the Democratic political machine headed up by . At the Jefferson, torch singers went from table to table singing mournful songs of love spurned.

Sanders’ engagement at the Blue Goose paid in tips, which he split with the vocalists at the end of the evening. His brother Roy marveled at the mound of coins and bills piled up on his younger brother’s dresser each morning. Suspecting that Joe had fallen in with the wrong crowd, Roy discovered the truth by following his younger brother to the Blue Goose.

On July 25, 1914, the police raided the Blue Goose and the Jefferson Café. The Kansas City Star reported, “About a hundred men and women patrons of the Jefferson and Blue Goose cabaret cafes rode to police headquarters early this morning because neither they nor their hosts, the café managers, had taken seriously the police order that the drinking lid must go on at the closing hour, which is midnight on Saturday night.”

After graduating from Westport High School in 1914, Sanders joined the Kansas City Oratorio and Choral Society. In exchange for free voice lessons, he provided piano accompaniment for choir rehearsals. Sanders learned the art of arranging by orchestrating the various voices in the choir. He developed an ear for harmony while performing around town with vocal groups. Later, Sanders’s mastery of harmony and arranging gave the Coon-Sanders Orchestra an edge over other bands.

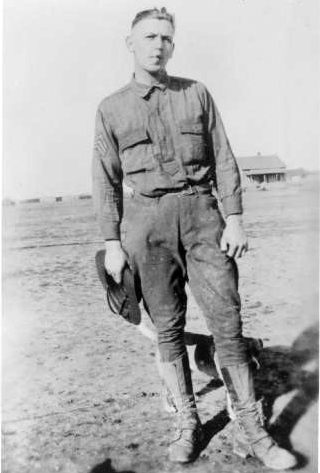

Sanders was drafted into the Army in October 1918, just before the armistice was signed between the allies and Germany. He was stationed at Camp Bowie near Fort Worth, Texas. Shortly after arriving at the base, Sanders participated in an amateur show, delighting his fellow recruits with his ragtime piano and vocals. Impressed by Sanders’ talents, the company commander transferred him to Headquarters Company to entertain at the officer’s mess. Sanders formed the Missouri Jazz Hounds, a four-piece jazz and ragtime ensemble that entertained officers and local society. The Jazz Hounds were so popular that after the conclusion of the war, local gentry offered the band long-term engagements, and officers at Camp Bowie delayed discharging band members to keep them in the area.

Coon-Sanders Reunited

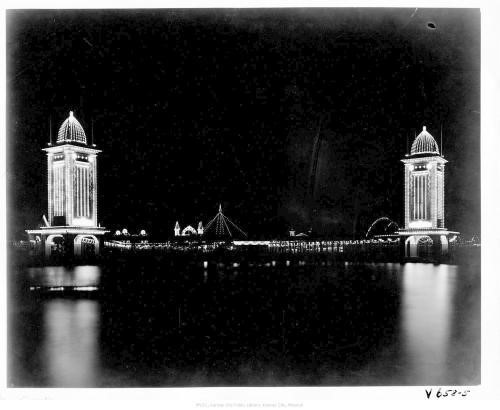

After Sanders was discharged from the service in early April 1919, he returned to Kansas City and resumed his partnership with Coon. The two formed a booking agency and a dance band known as the Coon-Sanders Novelty Orchestra. The band played country clubs, social events, dance halls, Electric Park, an Edison wonderland illuminated by 100,000 lightbulbs at 47th and Paseo, and private parties for the city’s elite.

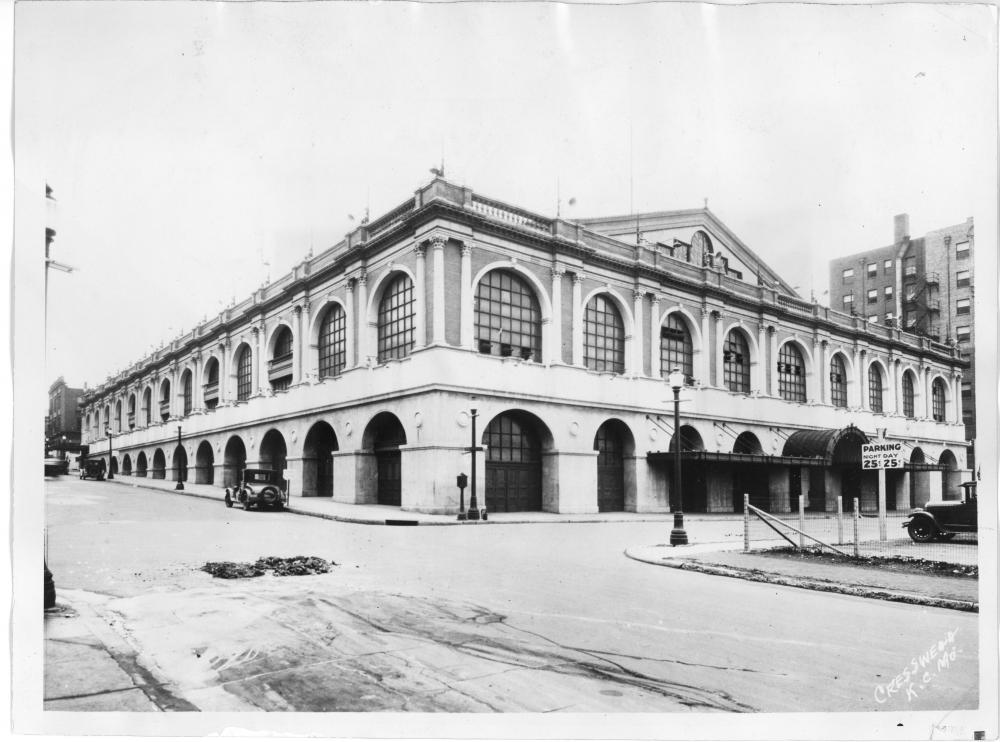

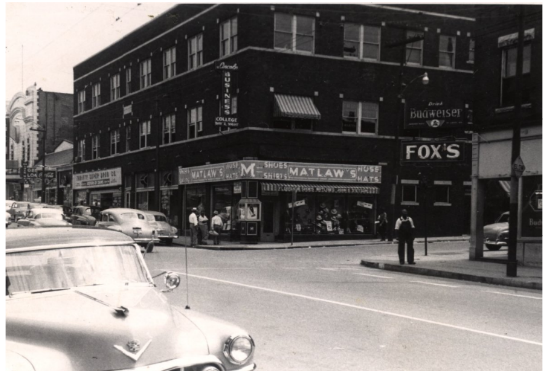

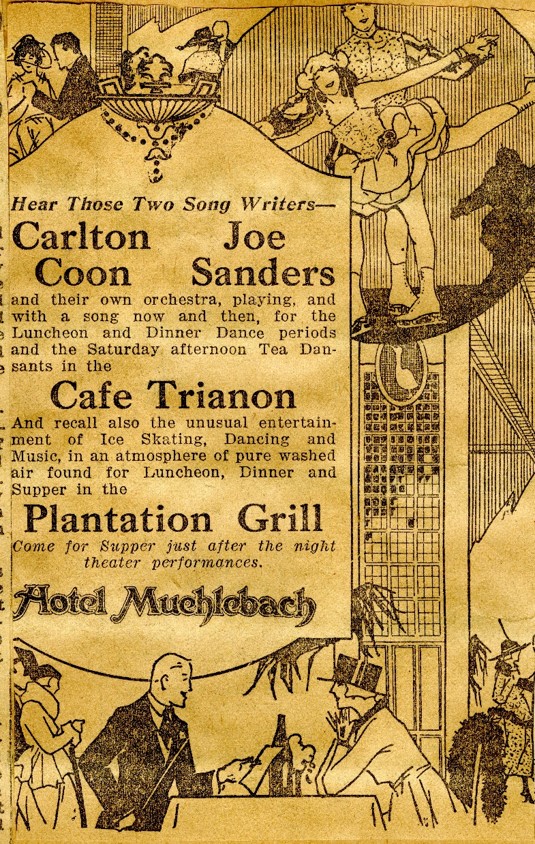

In early October 1919, the Coon-Sanders Novelty Orchestra opened at the Café Trianon in the 12-story, 500-room Hotel Muehlebach. Located on the southwest corner of 12th and Baltimore, the hotel was a popular gathering spot for Kansas City’s social elite. On opening night, May 17, 1915, 1,000 revelers streamed past the mahogany panels and black marble of the ornate lobby to celebrate in the hotel’s ballroom and two restaurants: the Café Trianon and Plantation Grille. Located upstairs, the Café Trianon was modeled after the salon in Marie Antoinette’s summer home near Versailles. French grey with ornate relief of gold and ivory accented the café’s Louis XVI motif. The band played daily for lunch and dinner dances and the Saturday afternoon Tea Dance. With tight vocal harmonies, entertaining stage antics, and danceable music, the Novelty Orchestra quickly became Kansas City's most popular band.

In September 1920, the band switched to the Plantation Grille, located in the lower level of the hotel. The Plantation Grille sported a southern antebellum theme. Murals depicting life from the veranda of a southern plantation lined the walls of the Grille. The band played for lunch, dinner, and supper. After-theater crowds flocked to the Café for supper. Taking advantage of their popularity with after-theater audiences, the band began playing matinees at the Doric, Newman, and other grand theaters downtown.

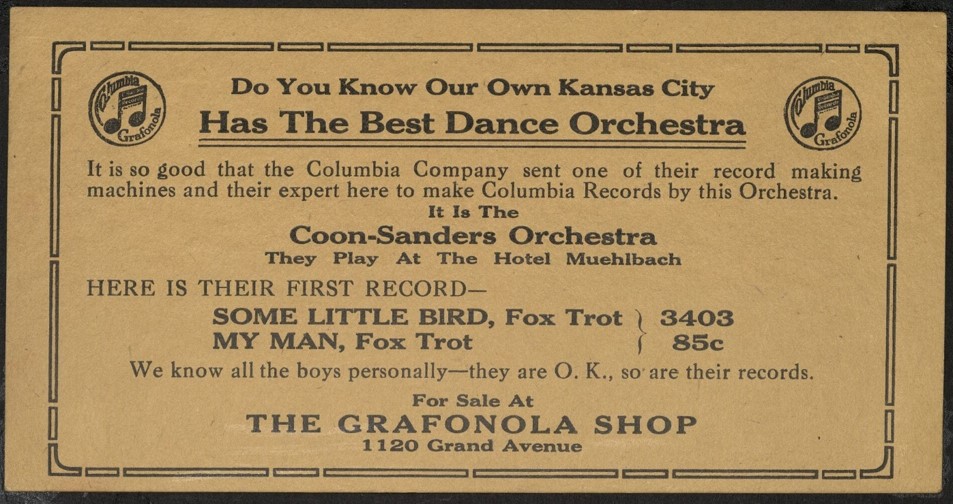

The band’s local celebrity led to a recording session in Kansas City for the Columbia label on March 24, 1921. Edward N. Burns, Vice President of Columbia Records, came to Kansas City to personally supervise the session. The session, held at the local branch office of Columbia Records, was reportedly the first local recording for national distribution by a major label. Four songs were recorded, with one novelty selection “Some Little Bird” issued to modest success.

Radio

Coon and Sanders quickly took advantage of another emerging media that would catapult them to national prominence - radio. WDAF, which was licensed to the Kansas City Star, signed on in early May 1922. WDAF was one of a handful of 500-watt stations, stretching from the East Coast to the Midwest. Because WDAF was centrally located and had little interference from other radio stations, its broadcast signal could be picked up from Maine to Hawaii and Canada to Mexico, when atmospheric conditions were right.

Like other early radio stations, WDAF broadcast civic events, lectures, acapella vocal renditions of popular standards, band concerts, classical recitals, coverage of sporting events, and other programming intended to culturally elevate and inform listeners. Coon and Sanders, with their on-air antics and danceable music, brought entertainment and hot jazz to the WDAF schedule and airwaves nationally.

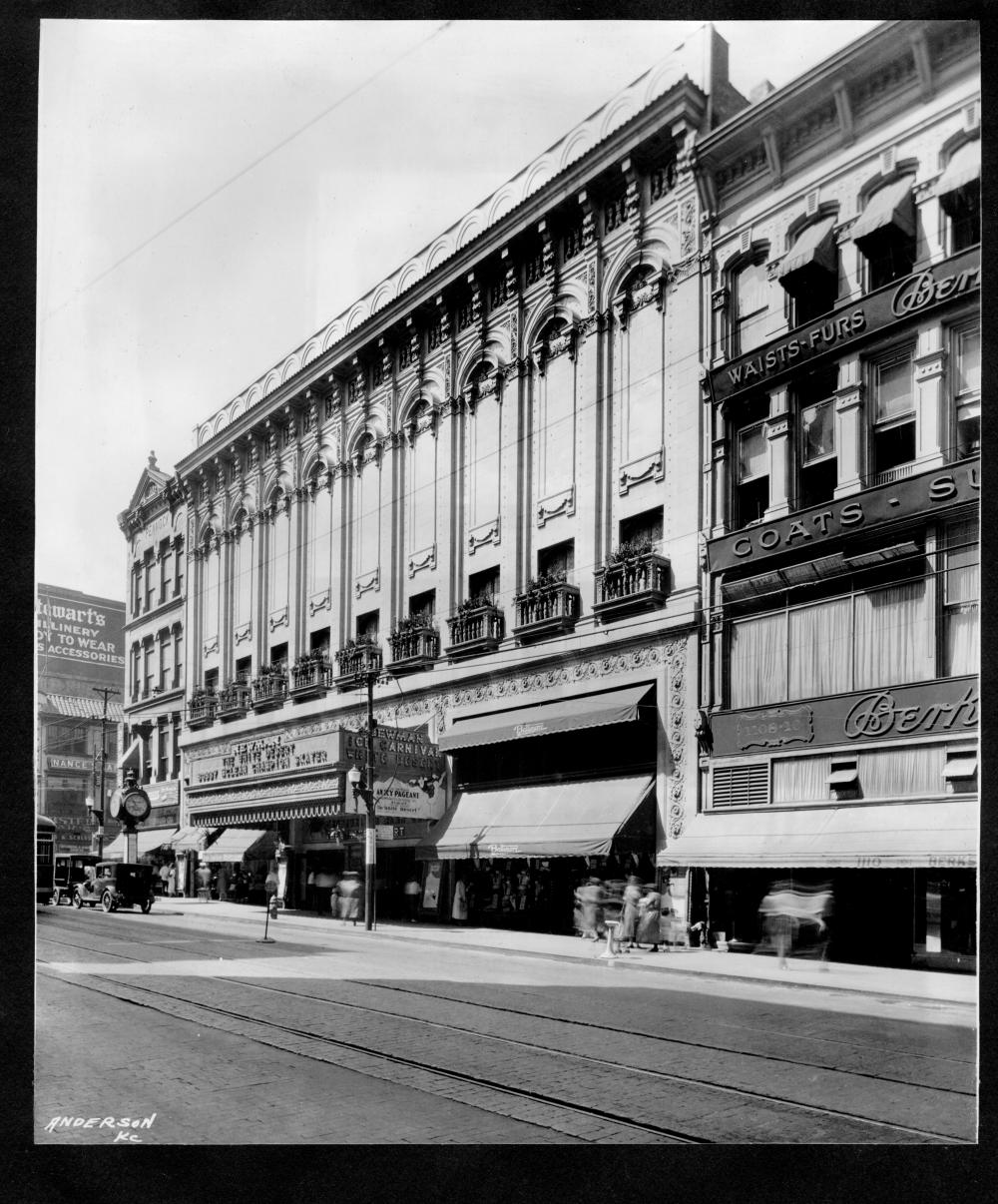

On September 22, 1922, the Coon-Sanders Novelty Orchestra made its debut on WDAF as part of a broadcast of the stage show at the Newman Theater, located on Main Street, just north of 12th Street. One of the largest theaters in Kansas City, the Newman could seat 2,000 patrons. Along with the stage show, the Newman featured silent films and Walt Disney’s early animation shorts, Laugh-O-Grams. The broadcasts from the Newman became so popular with listeners that WDAF offered Coon and Sanders their own program.

On Monday, December 4, 1922, the Coon-Sanders band launched a nightly “midnight radio program” broadcast over WDAF, between 11:45 p.m. to 1:00 a.m., from the Plantation Grille. During the broadcast, the announcer Leo Fitzpatrick commented to Coon and Sanders that “nobody will stay up to hear us but a bunch of night hawks [sic].” His off-the-cuff remark sparked an immediate reaction from listeners across the country. During the following week, 5,000 listeners from Canada, Mexico, and 37 states in the United States responded by letter or telegraph that they were indeed Nighthawks.

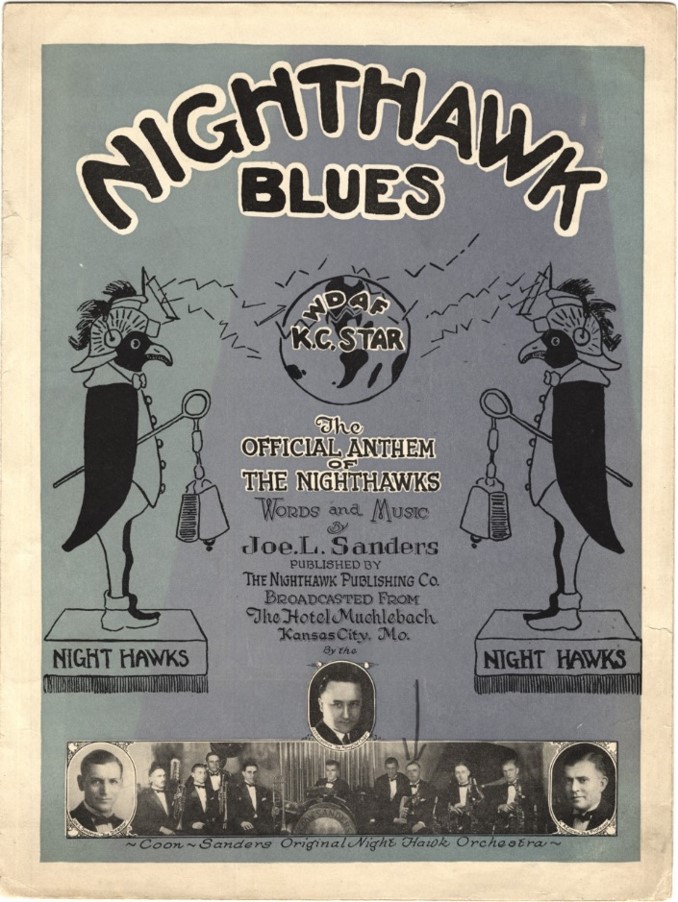

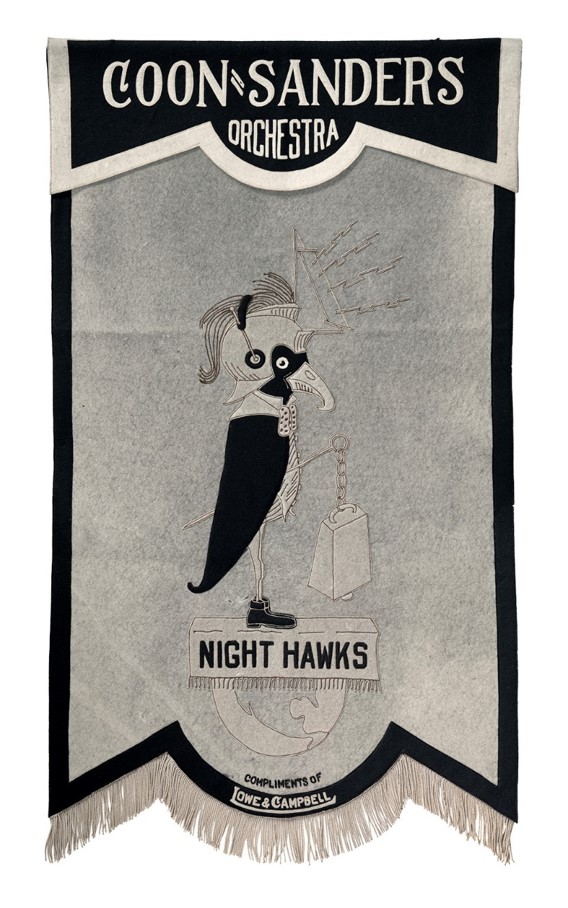

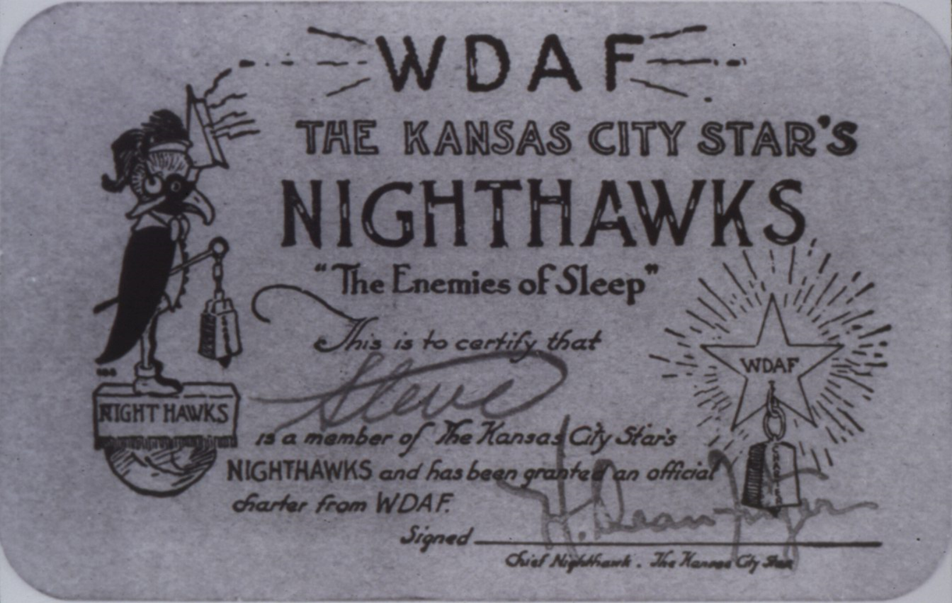

Realizing a good thing, Coon and Sanders changed the name of the band to the Coon-Sanders Nighthawk Orchestra. Sanders composed a new theme song, “Nighthawk Blues,” encouraging listeners to “tune right in on the radio, grab a telegram and say hello.” They also formed the first radio fan club, the Nighthawk Club. Coon and Sanders deftly used the Nighthawk Club to promote the band and radio as an entertainment platform. The Nighthawks issued cards and inducted each new member on the air by reading their name and home town to the ceremonious clank of a cowbell. Listeners across the country phoned in and wired their requests and appreciation. The Western Union and Postal telegraph offices rushed the telegrams to the Grille to be read over the air by Fitzgerald, Coon, and Sanders. During the first year, 37,000 listeners joined the club, known as the "Enemies of Sleep."

The Nighthawk Frolic was reportedly the first regularly scheduled radio program hosted by an organized band to be heard nationally. These pioneering broadcasts intimately connected listeners from across the country, as no other media had before. One fan explained, “Between hilarious and roof-rocking numbers, the boys used the mike [microphone] to convey friendly greetings and messages of cheer to hospitalized shut-ins and to loyal correspondents listening on battery-powered sets at points ranging from a lonely Canadian rancher’s hut to a ship off the Virginia coast.”

Chicago and New York

The band’s broadcasts and popularity caught the attention of club and resort owners across the Midwest. In the closing weeks of the band’s 1923-1924 season at the Plantation Grille, Jack Huff, the owner of the Lincoln Tavern, located just north of Chicago, sent the band a letter offering the band a summer engagement. Thinking the letter was a joke, Joe responded in kind. About a week later, Huff visited the Grille and made the band an offer in person.

In the summer of 1924, the Nighthawks played a three-month engagement at the Lincoln Tavern, a spacious roadhouse in Morton Grove located 20 miles north of Chicago. When Prohibition was enforced after January 1920, Chicago clubs were increasingly under scrutiny by federal law enforcement agencies. Circumventing the law of the land, a number of roadhouses sprung up in the northern and western suburbs of Chicago, where law enforcement was lax. The roadhouses varied in sophistication from rustic bars where patrons danced to records to spacious resorts that featured floor shows and bands. The Lincoln Inn and its nearby neighbor, The Dells, were the two biggest resorts in the area.

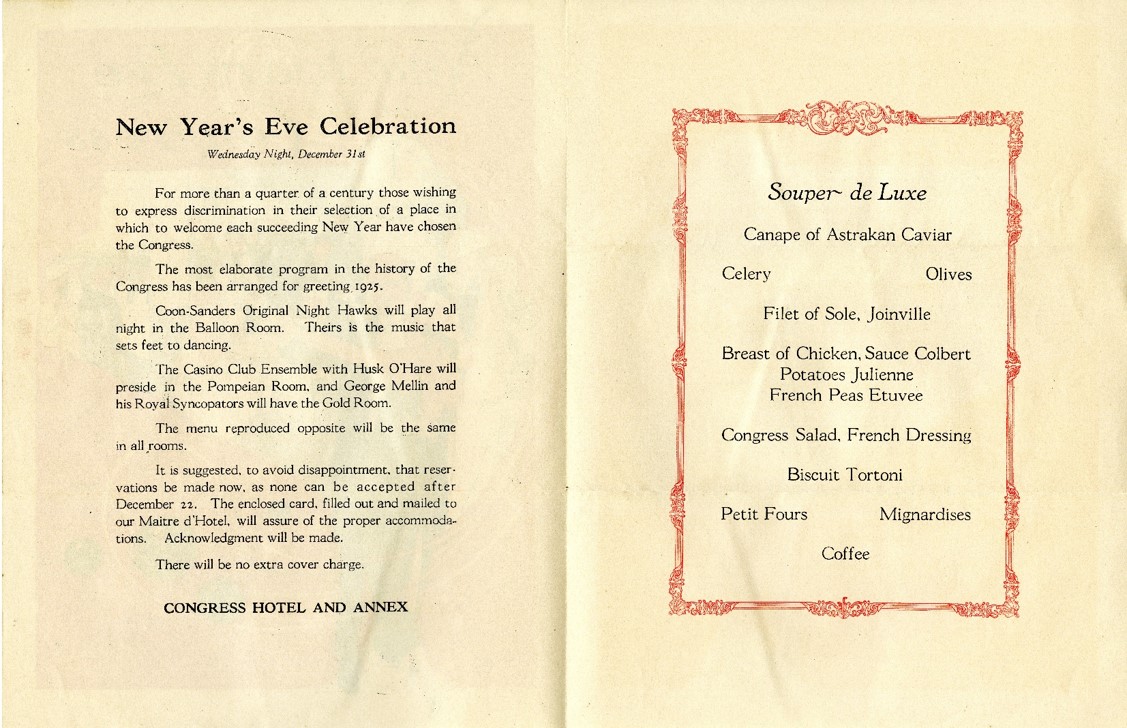

That summer, Jack Huff introduced Coon and Sanders to H.L. Kauffman, the manager of the stately Congress Hotel in Chicago. Impressed by the band’s strong draw at the Lincoln Tavern, Kauffman offered the band a fall engagement at the hotel’s cavernous Balloon Room. Like the Hotel Muehlebach in Kansas City, the Congress was a gathering spot for the city’s social set.

On opening night, the Nighthawks sold out the Balloon Room at $15 per plate. The immensity of the Balloon Room dwarfed the bandstand nestled at one end of the semi-circular dance floor. Sanders later marveled how during the opera season the Balloon Room was “ablaze of color and dazzling jewels.”

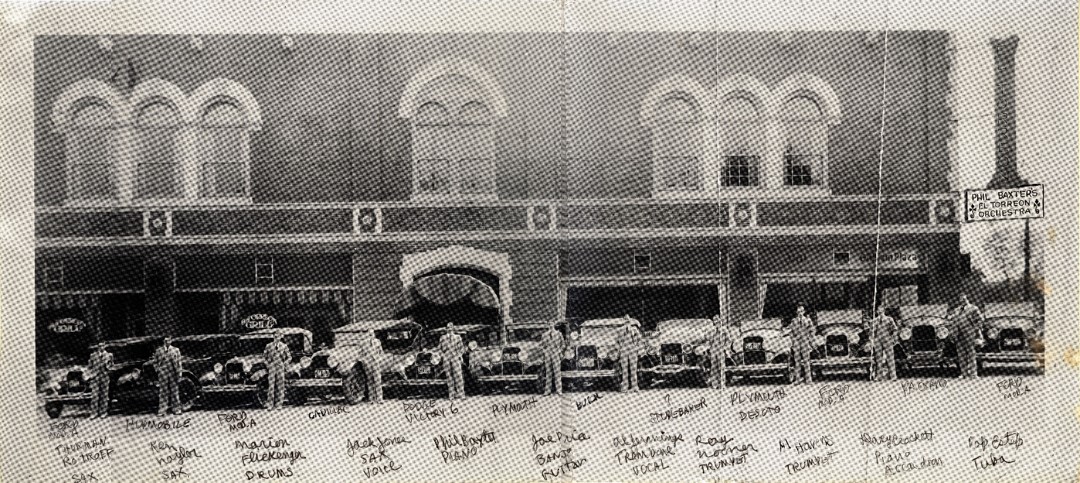

The Nighthawks moved their headquarters to Chicago, playing extended engagements at the Congress Hotel and the Blackhawk restaurant. During the summers they toured the country by train or caravan style in Auburn and Cord automobiles. Other summers, they played at the Dells, a roadhouse in Morton Grove, Illinois.

Although the Nighthawks had established Chicago as their new headquarters, they remained associated with Kansas City. Magazine articles about the Nighthawks often touted the band’s legendary broadcasts from Kansas City. Coon maintained a home for his family in Kansas City. He and Sanders often returned to Kansas City during breaks in their busy schedule.

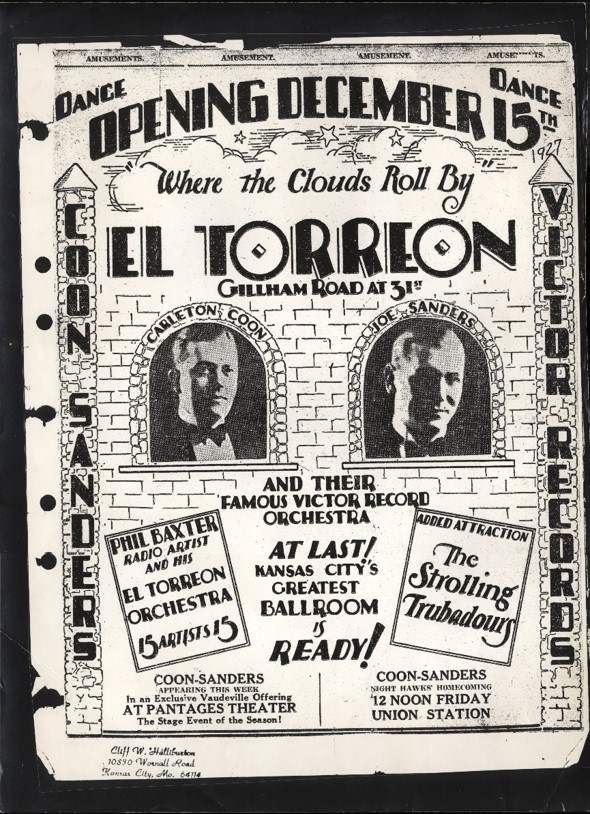

In December 1927, the Nighthawks returned to Kansas City for the grand opening of the El Torreon Ballroom. Since the advent of the Jazz Age, the nation had become dance crazy, creating a demand for dance halls and ballrooms. Young women called flappers, shed societal taboos, bobbed their hair, raised their hemlines, and danced the Charleston, Black Bottom, and other dance crazes then sweeping the nation. Stylishly dressed young men with slicked back hair, sporting hip flasks, flocked to dance halls and ballrooms to hear their favorite bands.

Throughout the 1920s, grand ballrooms opened across the country: New York’s Roseland Ballroom opened in 1919, the Graystone Ballroom in Detroit opened its doors in 1922, Chicago’s palatial Aragon Ballroom made its debut in 1926. In Kansas City, the Pla-Mor and El Torreon ballrooms opened within a month of each other. The Pla-Mor, known as the “Million Dollar Ballroom” opened on Thanksgiving evening, 1927. The wildly popular Jean Goldkette Orchestra presided over opening night festivities. Located at 32nd and Main, the Pla-Mor featured an indoor ice hockey rink, a bowling alley on the ground floor, and a spacious ballroom upstairs. The ballroom’s spring-loaded dance floor could accommodate 3,000 dancers.

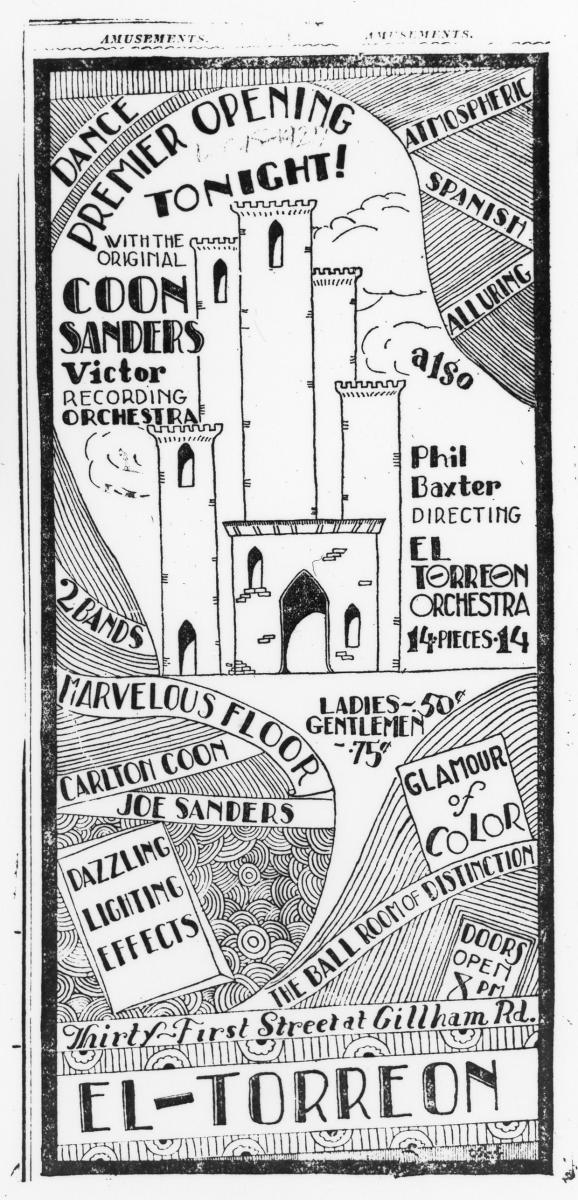

On December 15, 1927, the El-Torreon Ballroom opened at 31st and Gillham Road, a few blocks east of the Pla-Mor. The El Torreon sported a Spanish Mission motif with arched doorways and a vaulted ceiling. An enormous crystal ball adorned with 100,000 mirrors hung over the dance floor which could accommodate 2,000 dancers. A balcony surrounded the dance floor on three sides.

The Nighthawks arrived in Kansas City two weeks ahead of opening night at the El Torreon. The band drove to Kansas City after closing out at the Chase Hotel in St. Louis. The next day, they hauled their bags to Union Station for the celebration of their “official” arrival. They were met in the vast marble lobby of Union Station by a huge crowd of fans and a bevy of local officials who gave them the key to the city. Band members then piled into new Fords for a motor car parade that snaked through downtown to the Pantages Theater at 12th and McGee, where they played a week-long engagement.

The next week, the Nighthawks opened at the El Torreon on a double bill with the El Torreon Orchestra directed by Phil Baxter. The El Torreon Orchestra opened the night’s festivities with El Torreon, a new theme song composed for the new venue by Phil Baxter. That night, the 3,000 dancers and onlookers that crowded the El Torreon gave Baxter and the El Torreon Orchestra a warm welcome, and then went wild and surged forward when the Nighthawks hit the stage. After closing out the weeklong engagement at the El Torreon, the Nighthawks stayed in Kansas City through Christmas, celebrating with relatives and friends.

After wrapping up their winter tour, the Nighthawks returned to the Blackhawk restaurant in Chicago, where they broadcast over WGN. The Nighthawks continued broadcasting from the stage of the Blackhawk through the early years of the Great Depression.

The stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression devastated the entertainment industry. Record sales plummeted from a record high of 104 million in 1927 to 6 million in 1932. During the same time, production of phonographs dropped from 987,000 to 40,000. While sales of records and phonographs floundered, the radio industry boomed. Destitute families would sell everything but their radios, which kept them entertained and connected to the world. Clubs and ballrooms across the country closed and theaters cut back on entertainment, leaving many leading bands struggling. Due to Coon and Sanders’s popularity on radio, the Nighthawks managed to continue recording and move up to more prestigious engagements, even during the depths of the Great Depression.

In 1931, MCA arranged an 11-month engagement for the band at the New Yorker Hotel’s Terrace Room. Located across from Pennsylvania Station, the 43-story, 2,500-room hotel dominated New York’s skyline. According to Sanders, “our opening on Wednesday night, Oct.7th, was the most sensational of the year—and one of the most successful little old New York had ever seen. Every ‘big name’ in show business was present.”

The Nighthawks broadcast nationally over the NBC network. The band appeared regularly on the Lucky Strike Hour, which was hosted by syndicated newspaper gossip columnist Walter Winchell. Sponsored by Lucky Strike Cigarettes, the program featured a short gossip report by Winchell, guest appearances by stars like Jean Harlow (another Kansas City native) and William S. Hart. Sanders reported, “The band gained steadily in popularity and we were soon doing the business of the town—we had ‘arrived’ on Broadway—or, to speak correctly—west of Broadway.”

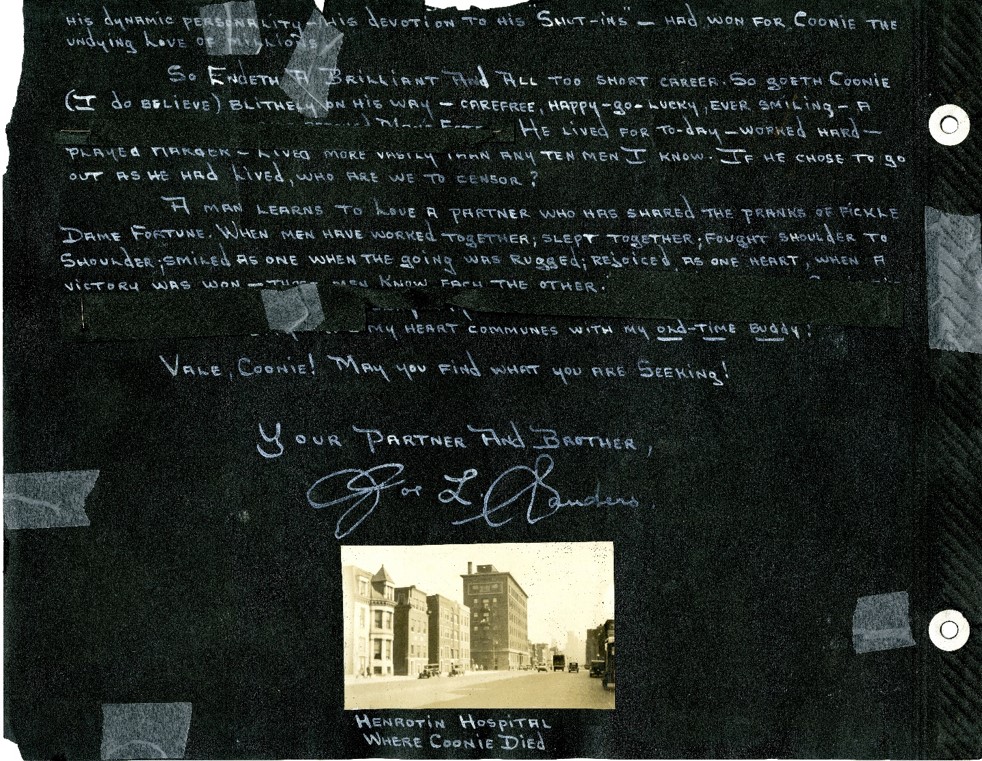

Just as the Nighthawks reached the pinnacle of success, disharmony between Coon and Sanders and a medical emergency brought the group tumbling down. Coon and Sanders had long been heavy drinkers. Since 1930, Coon’s excessive drinking caused him to be unreliable and flub the lyrics of songs he knew well. Sanders grew to resent covering for his old partner. Compounding matters, both men grew to dislike New York and longed to return to Chicago.

Sanders and other band members’ spirits were briefly elevated by their return to Chicago for an engagement at the College Inn, opening Friday, April 8, 1932. The band members’ exuberance was short-lived, however. On April 30, 1932, Coon entered the hospital in critical condition, suffering from blood poisoning, resulting from an abscessed tooth. The Coon-Sanders Nighthawk Orchestra essentially died with Carleton Coon on May 4, 1932. Coon's body was returned to Kansas City for burial at the Mount Moriah Cemetery. His funeral was one of the biggest that Kansas City had ever witnessed, with a procession that stretched for miles on Holmes Road south of 105th Street. Sanders continued to lead the group as Joe Sanders’ Nighthawk Orchestra, but the magic of the Coon-Sanders Original Nighthawk Orchestra was gone. Joe disbanded the group on Easter Sunday 1933.

Joe relocated to Hollywood for a short time, writing movie scores without much success. In 1934, he formed a new group, Joe Sanders and His Orchestra. Sanders recorded for the Decca label and remained popular in the Midwest, but never enjoyed the national success he achieved as co-leader of the Nighthawks. In 1952, he disbanded the group and retired to Kansas City, where he died on May 14, 1965.

A longer version of this article is published in the book, Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era (University Press of Kansas, 2018), edited by Diane Mutti Burke, Jason Roe, and John Herron.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.