N. Clark Smith

- Date of birth: July 31, 1866

- Place of birth: Leavenworth, Kansas

- Home: 2313 Tracy Ave.

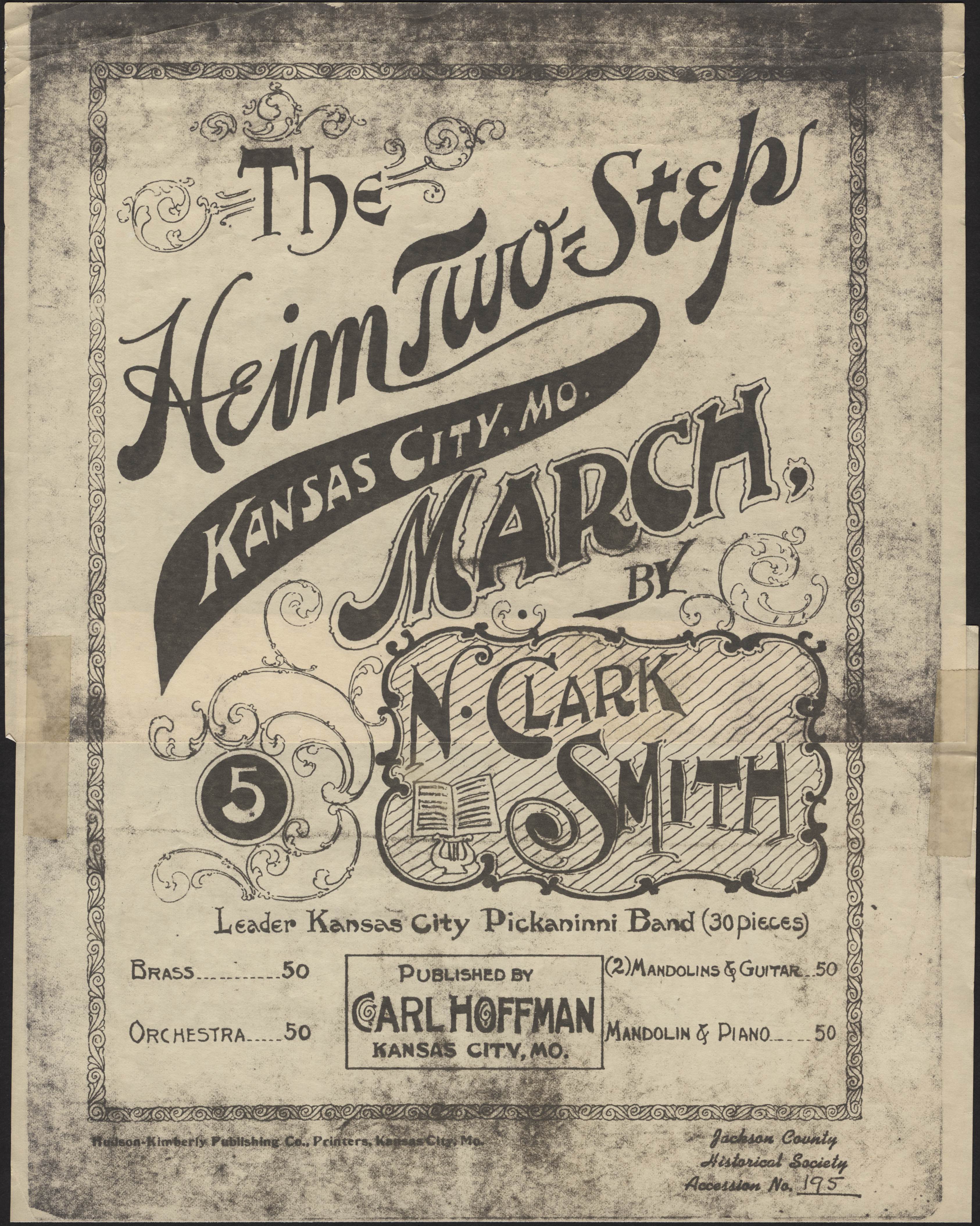

- Claim to fame: renowned musician, publisher, band leader/music educator, and composer known for his arrangement of African American spirituals, particularly “Steal Away to Jesus.”

- Spouse: Laura Alice Smith (Lawson)

- Also known as: Major N. Clark Smith, Clark Smith, N.C. Smith, Professor, Captain, Major. Often referred to as Nathaniel Clark Smith in scholarship.

- Date of death: October 8, 1935

- Place of death: 2313 Tracy Ave.

- Cause of death: complications following stroke

- Final resting place: Highland Cemetery, Kansas City, Missouri

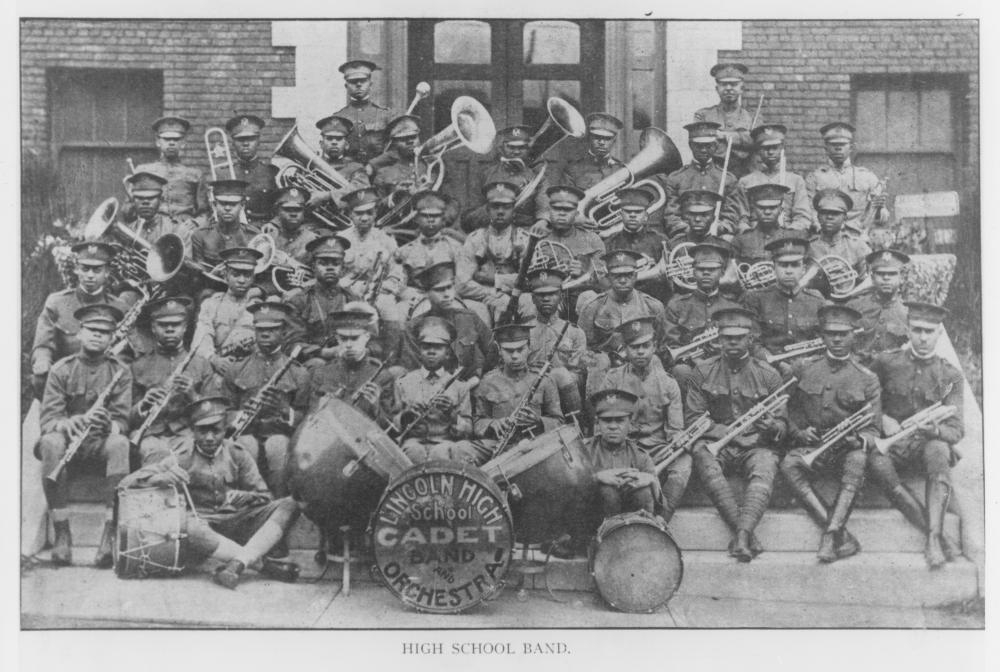

Harlan Leonard once described N. Clark Smith’s impressive persona as the segregated Lincoln High School’s band leader in Kansas City, saying that Major Smith held a “commanding personality”:

He was short, chubby, gruff, military in bearing, wore glasses, and was never seen without his full uniform and decorations. His language was rather rough and occasionally shocking to the few young ladies who were taking music classes, though never offensive. Major Smith simply ran a tight ship. . . . He drilled the Lincoln marching bands until they were the best in the area, some said the best of their kind in the Middle West.

N. Clark Smith is known for his work as a prominent black musician and composer who worked with spirituals, as well as for his contributions to music education as a decades-long music instructor. Smith joined historically black Lincoln High School as bandmaster and military instructor in 1916. He instructed music twice a week and drills three days a week, and by the end of his first year at Lincoln High, the band members who could play instruments increased from five to 30 students.

Smith’s direction and rigor as band leader at Lincoln High School from 1916 to 1922 produced several of Kansas City’s early jazz musicians, including Walter Page, Julia Lee, Harlan Leonard, Leroy Maxey, Lammar Wright, Jasper Allen, and DePriest Wheeler.

Smith also organized a girls’ glee club and a boys’ glee club, in addition to a 15-piece orchestra. The glee clubs performed “popular standards and spirituals,” including Smith’s own arrangement of Steal Away to Jesus, one of his most widely known works. Jazz was not part of Lincoln High’s curriculum, but many Kansas City jazz musicians studied under Smith, and Smith himself composed and performed pre-jazz musical styles, including spirituals, ragtime, brass band music, and, as was common during the 19th and early 20th centuries—minstrelsy.

At Lincoln High School, Smith conducted his bands much like an army commander, and on at least one occasion he struck a student repeatedly with a ruler for playing poorly. However, Smith seems to be remembered by his students with respect and admiration. Saxophonist William Saunders, for example, recalled the incident in which Smith hit him on the head, saying, “I know what music is.” As a music instructor, Smith worked more frequently with young adults (high school and college) than adult professionals.

The seeds for Smith’s long-spanning career began early, from childhood. Smith’s own father served as quartermaster and chief trumpeter in the 24th Infantry band and later as quartermaster sergeant at Fort Leavenworth, and N. Clark Smith apparently received music instruction at Fort Leavenworth under German bandmaster, Carl S. Gung’l, who was known to mentor black students. Within JROTC, Smith achieved the rank of major, and Smith was often referred to as “Captain” or “Major” by students and within publications.

Smith’s early life has largely been mythologized, both by himself and by the press. Recent research argues that N. Clark Smith, while often referred to after his death as “Nathaniel Clark Smith,” never appears to have possessed that name during his actual life. Music historian Peter Lefferts finds that the most closely documented and probable N. Clark Smith during this period was an individual named “Nora Clark Smith.” Lefferts writes, “Smith suppressed his first given name (the N name) his entire adult life. He never used his first name, and probably disliked it. In his lifetime he is always N. Clark Smith or Clark Smith or N. C. Smith (often Prof. or Capt. or Major Clark Smith), and he signs with a characteristic NClark first name, all run together.”

Beyond his mysterious name, Smith crafted multiple narratives about his early life that were partly or entirely false, most likely including a story about his father having a friendship with Frederick Douglass. Smith enjoyed telling people about playing music with Douglass when he was eight years old, but given Douglass’s tours overseas, it seems highly unlikely he would have been in Kansas during that time. Smith’s black contemporaries often claimed Douglass as a mentor in their memoirs as a means of legitimizing their own work; finding it in Smith’s own narrative is not surprising. In addition, as Smith grew older, his birth date moved up, and he appeared to grow younger. Biographers have explored a range of possible birth years for Smith, spanning a decade. Citing census records, Peter Lefferts identifies Smith’s birth year as 1866, but previous biographers had taken Smith’s tombstone at its word: July 31, 1877. The same 1877 birth date appears on Smith's death certificate, but even that information was reported by his wife who was similarly lying about her own age. A birth date of July 31, 1866, is most likely correct based on the 1870 census. Managing his date of birth would also have allowed Smith’s chosen narratives to shift for better credibility. Smith’s students and the wider public claimed he was always dressed in his full uniform and decorations, always “playing the part” of major. These inconsistencies in narrative and timeline thus seem to reflect Smith’s concerns with maintaining his authority and social capital.

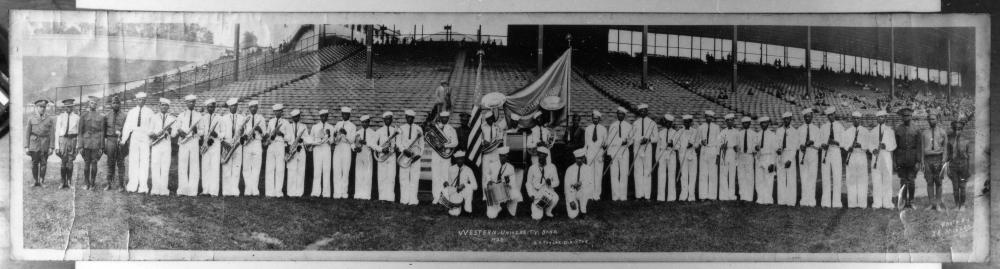

Scholars do agree on some key details about Smith’s early life. He was born in Leavenworth, Kansas, to Dan and Maggie Smith. Smith’s professional endeavors included printing and publishing. He published The Advocate, Leavenworth’s African American newspaper, in 1888, and for a brief period he also produced another black press, Afro-American Letter (1890). He traveled widely during his lifetime, crossing much of the United States, visiting Cuba as an enlisted band leader during the Spanish-American War, and touring Hawaii, Australia, and New Zealand as part of a minstrel show. Smith was highly sought after as a musician and band leader, building an impressive resume that included positions at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Western University in Quindaro, Kansas (now Kansas City, Kansas), multiple institutions in Chicago, Lincoln High, and Sumner High in St. Louis. Smith accepted the position of music director at Western University in 1895, teaching band, strings, and serving as Commandant of the JROTC program there. At the same time, he worked at the Hoffman Music House and led his Wichita minstrel band, the same group that later toured the globe. One of those band members was Wilbur Sweatman, whose 1918-19 recordings were among the earliest jazz recordings made by African Americans.

While Smith may not have had a factual connection to Frederick Douglass, he did form other valuable and noteworthy relationships throughout his career. One of Smith’s key connections (although sometimes they seemed to butt heads) was to Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Smith composed the Tuskegee Institute March in honor of Washington, advanced the music program at Tuskegee, and organized its touring bands, but the letters between Smith and Washington (several of which are published in The Booker T. Washington Papers, volumes 10-12, by L.R. Harlan and R.W. Smock) demonstrate that there was friction between the two of them concerning visions of artistic direction and differing strategies for racial uplift.

During his time as bandmaster at Tuskegee, Smith’s self-assurance in his students’ repertoire of styles seemed to clash at moments with Washington’s concepts of “modesty and conservatism.” Washington directed his letters to “Captain Smith” and critiqued the lack of “plantation melodies” in the African American band’s production. At one point in the summer of 1913, Washington boldly asserted, “If one goes to hear a Mexican band he expects to hear music suited to the atmosphere of Mexico, that is peculiar to Mexico, and consequently when one goes to hear a colored band or Southern band he expects to hear something different from a band in the North.” When Smith at times pulled from classical styles, rather than black spirituals, Washington expressed his displeasure.

Washington also took issue with Smith’s “self-advertisement” in the Tuskegee band’s playbills, writing, “I do not think it does you or the institute any good to be advertised as the greatest colored band master. . . . It is better for the people not to be disappointed by getting more than they expected.” Washington’s accusation of self-advertisement seemed to make a jab at Clark as being prideful, rather than displaying humility. This is not surprising considering the moral tenets regulated by Washington at Tuskegee during this time. Washington’s annoyance with the advertisements stemmed from his voiced concepts of “modesty,” or respectability politics, and it appeared that he disliked Tuskegee’s talents being equated with Smith as an individual.

In response to Washington’s criticisms, Smith sent a rather terse letter, when one considers the amount of power Washington held both within the community of Tuskegee and beyond. Discussing Washington’s several critiques, including one about the young men’s quality of singing, Smith wrote, “I am sure you have not the slightest idea of how much worry, strength, energy, and vitality is going out in handling 47 boys and looking after every detail . . . I note with much regret that you constantly nag me about the singing of the students in the band. You must remember that this is not my first trip. . . .” Smith then described his experiences and accomplishments and defended the advertising plates that espoused him as the “greatest colored bandmaster,” which were made without his involvement. About his choices in music styles and the expectations of white people for entertainment, Smith wrote, “The white people invariably call for classic selections, which we give them to the best of our ability. The press speaks for itself.”

Shortly after this exchange of letters between Washington and Smith, Smith asked for leave, both because of exhaustion from touring and apparently because of Washington’s treatment of his band leader. When Washington died in 1915, Smith returned to Kansas City and began what would be a long-lasting legacy at Lincoln High School.

While at Lincoln High, Smith continued to compose music, including Negro Folk Song Suite, The Crucifixion, and Prayer from the Heart of Emancipation. The number of students he instructed at Lincoln High is unknown, but the several successful jazz musicians he helped produce between 1916 and 1922 speak volumes about this skill as a music educator. Smith’s skills as a band leader were so renowned that eventually the Pullman railroad car company asked him, for a substantial salary, to organize and instruct large numbers of singing porters. This move led to further positions in Chicago, including directing a Newsboys Band for the Chicago Defender newspaper and a brief period teaching at Chicago’s Wendell Phillips High School.

In 1935, Smith finally retired and moved back to Kansas City, following a stint at Sumner High School in St. Louis. On August 8 of that year, after attending the Joe Louis and King Levinsky fight in Chicago and arriving safely back home in Kansas City, Smith suffered a stroke that rendered him ill. He died on October 8, 1935, at his home at 2313 Tracy Avenue. African American publications throughout the United States released the news of Smith’s death with long obituaries and extensive accounts of his accomplishments: musician, composer, band leader, music educator, and publisher. Over six decades of music production and education, Smith influenced many black musicians in Kansas City and black communities across the entire United States. Throughout his life, he had been referred to as the “greatest colored bandmaster,” and the Kansas City Sun wrote that he was “the greatest colored bandmaster not only of his race, but that America has produced since the days of Patrick Gilmore.”

Additional support from the Missouri Humanities Council.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.