Harbinger of the New Deal Coalition: The Pendergast Machine and the Liberal Transformation of the Democratic Party

One of the defining political trends of the mid-20th century was the transition of black voters from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party, accompanied by a major shift in the party’s policy platform toward social liberalism and civil rights. Nationally, this change is usually dated to the latter half of the New Deal, roughly around the election of 1936. In Kansas City and the state of Missouri, however, it happened much earlier and in surprising circumstances that greatly influenced national affairs in later years. In fact, a strong argument can be made that the liberal transformation of the Democratic Party started with Kansas City’s own political machine, led by "Boss" Tom Pendergast.

The Kansas City Democrats of the interwar period remain one of the most notorious local party organizations in American political history. Tapping into the profits from Kansas City’s status as the central Plains’ leading railroad stopover and exchange point for livestock and grain, Tom's older brother, Jim Pendergast, founded the original Pendergast operation. As a West Bottoms saloon owner, Jim parlayed his popularity into a long career as an alderman and built a relatively textbook city machine: Irish immigrant politicians exchanged access to public jobs, credit, and their own ad hoc social safety net—at a time when the public one was almost nonexistent—for the support of voters in teeming industrial neighborhoods.

In Alderman Jim’s First Ward, the city’s poorest immigrants, along with black refugees from the Missouri countryside in a section called “Hell’s Half Acre,” lived crowded in the flood plain next to the packinghouses, stockyards, and railyards, or in shanties strewn up the bluffs. They shared the neighborhood with one of the country’s most active and seedy red-light districts, catering to trail’s end cowpokes and travelers passing through the adjacent railway station. From this domain along the Missouri River, also including the Italian and black North End, Pendergast’s “Goat” faction (named for their gruff working-class image and the craggy, sloping terrain many of them lived on) battled furiously for control of the Jackson County “Democracy” with the Rabbits, based in the newer and more upscale neighborhoods east of Prospect and led by Joe Shannon.

After his brother’s death in 1911, Tom took over the machine and built his brother’s organization into something much more grandiose. By the late 1920s, he had created a de facto regional government that Tom ran openly from his office in the Jackson County Democratic Club at 1908 Main Street. No longer needing any appointed or elected office to secure votes and control over local government, and with a distinctive bald head and cigar, he embodied the very image of a political boss. Pendergast remade the city and gained a fortune in the process, reaping millions from government contracts awarded to his Ready-Mixed Concrete company and a network of other companies engaged in paving and building.

Most surprising, and despite Boss Tom's lack of personal interest in drink, music, or social justice, he accidentally sponsored the growth and cultural efflorescence of Kansas City’s black community, concentrated in the East Side near downtown. The legally permissive environment allowed Kansas City’s famous, influential nightlife and jazz style to develop, and a complex alliance grew between the Democratic machine and the black community. With the unique coalition that emerged, the Pendergasts gradually realized their greatest significance in American political history.

The Pendergast Machine’s real historical importance, quite simply, is that they helped create and put in power the Democratic Party as we now know it, in Missouri and to some degree nationally: liberal-leaning, tolerant, heavily urban, and ethnically diverse, the political home for African Americans and most new immigrant groups by huge margins. Before the New Deal existed, Kansas City’s Irish Catholic ward-heelers helped put together the basic elements of the coalition that, when replicated nationally, handed the presidency to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It saw blacks, immigrants, workers, and just enough “southern” whites—like Harry S. Truman—join forces behind a vision of a government that helped ordinary people live their lives rather than judging what they did with them. Ruthlessly practical and non-ideological, it was socialism Kansas City-style, offering relative justice, cheap drinks, and public works for all, regardless of class, creed, or color, especially if they voted the straight Democratic ticket.

The Missouri Bellwether

Kansas City’s path to a major role in changing the Democratic Party came from the state of Missouri’s outsized influence in national Democratic affairs during the early 20th century. In the 1920s it was still the seventh largest state in population and electoral votes, bigger than California or Michigan. It was a true bellwether that combined elements of the industrial Northeast, the cattle-ranching West, and the rural South, with industrial cities to counter-balance its rural interior. More than just a “swing” state, Missouri’s electoral results were also absurdly predictive of the final national outcome: no winning presidential candidate failed to carry it in the 20th century, and no Democrat before Barack Obama ever won the presidency without it. Missouri’s national significance showed in the fact that it hosted eight national political conventions between 1876 and 1928 and was the only state to be given two Federal Reserve banks.

Many nostalgic stories of the Missouri bellwether and the Pendergast machine have been told, but usually without much mention of what we can now see as the crucial element of race. The shift of black voters away from the party of Abraham Lincoln, and a steady flow of white conservatives out of the same party, was a defining change in modern American politics.

On the one hand, Missouri was a haven of relative “racial liberalism” as far the former slave states went; most notably, unlike every ex-Confederate state, African Americans were never disfranchised after the end of Reconstruction. Missouri’s cities proved unusually attractive places for black migrants from the deeper South and rural areas to resettle, well in advance of the World War I–era “Great Migration” to the northern cities. On the other hand, racial liberalism was practiced with great inconsistency in Missouri. The western Missouri border region, stretching down to Oklahoma and Arkansas, fully participated in the new racism that spread through the Midwest in the 1910s and ’20s. Reemerging as a public fraternity in response to the popularity of D.W. Griffith’s blockbuster film, The Birth of a Nation, in which the Ku Klux Klan were depicted as heroic cavalry riding to the rescue of endangered whites, the Klan became a powerful social and political force in places like Indiana and Missouri. Racial pogroms and panics emptied many rural towns and counties of their black populations; in the most infamous Missouri case, armed white mobs killed three men and banished the entire black populations of Pierce City and four other southwest Missouri towns in response to a 1901 murder.

Nor were things necessarily much better in the cities where blacks moved to escape the terrors and poverty of rural life. Open racism in politics and journalism was always an option, despite the fact that blacks voted. The standard-bearer for Kansas City’s Democrats in those days was the splenetic Senator James A. Reed, who made himself a presidential contender by turning against Woodrow Wilson, his own party’s president, and mounting a starkly racist crusade against the League of Nations. Reed’s main argument was that by joining the League, the United States would put itself on the same level as, and would potentially have to submit to the decisions of, non-whites.

More importantly for African Americans, their ability to live freely and unmolested in Missouri’s major cities was under constant challenge. After the courts struck down formal segregation ordinances, whites turned to market manipulations, legal chicanery, and violence in their efforts to confine blacks to certain neighborhoods. Just as serious was the sinister combination of neglect and violent overzealousness that blacks had long suffered at the hands of Kansas City law enforcement.

"The Negro Democracy" and the Balance of Power

Despite all this, sophisticated black political leadership managed to develop in Kansas City. Black leaders in politics and business sought to extract the best treatment from the white majority and wring the maximum influence over the white power structure they could. Sometimes this was not very much, but in Kansas City it was crucial to a transformation that had national implications in the long run. Newspaper publishers Nelson Crews, of the Rising Sun, and staunch Republican Chester Arthur Franklin, of the Sun’s successor paper The Call, were the two most important voices. Less well known, but especially significant for our purposes, was a black leader who emerged among Kansas City’s Democrats: Dr. William Thompkins.

Thompkins had grown up a Democrat, working at the Madison Hotel next to the State Capitol in Jefferson City and marching at the head of local Democratic parades. In 1906, after medical school in Colorado and an internship at Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., Thompkins moved back to Missouri to set up a medical practice in Kansas City. For the next three decades, helped by his close friend and nightclub owner Felix Payne, Thompkins made himself a pillar of the Democratic side of Kansas City politics, vigorously embracing the difficult task of selling Democratic candidates and platforms to black voters.

William Thompkins was thoroughly convinced that “the party of Jefferson and Jackson offered the best ethics for the welfare of the Negro race.” This surprising statement of fealty to two slaveholding Democrats addressed their perceived egalitarianism and hostility to the power of wealth, at least as taught by Democratic speakers and writers of the day. Thompkins and his fellow black Democrats were also seeking to set an independent political course, angry at the Republicans’ paternalist expectation that the former slaves and their descendants would remain forever loyal and docile in gratitude for the party of Lincoln’s act of charity in freeing them.

In 1914, Thompkins’s unbeatable combination of medical skill and Democratic credentials earned him an appointment from a Rabbit mayor, Henry Jost, as the first black superintendent of Kansas City’s black hospital, known as General Hospital No. 2; up to that time, even segregated facilities typically had white medical staffs. Thompkins’s and Jost’s association illustrated some of the ongoing dynamics in Kansas City politics. The big local issue in 1914 was a new franchise for the Metropolitan Street Railway Company. Middle-class white reformers and the Star opposed the deal; the Democratic machine and the black community supported it out of concern for the jobs the streetcar company provided. The machine won, and Mayor Jost both appointed Thompkins to his hospital post and censored the Kansas City premiere of The Birth of a Nation.

One advantage the early "Negro Democracy" in Kansas City had was the fact that they often held the balance of power in both general elections and intraparty Democratic struggles. Besides the Goat-Rabbit divide, the Democratic machine was comprised of numerous other neighborhood fiefdoms capable of shifting their allegiances under the right circumstances. Before 1925, Tom Pendergast and his Goats controlled only the northern and western river wards. Joe Shannon’s Rabbit base was in the northeast, especially in the Ninth Ward, where Kansas City abutted rural Jackson County. Other neighborhoods had their own bosses, such as Miles Bulger (the “little czar” of the Second Ward on the South Side), who lined up with the Goats or Rabbits as it suited them. Thompkins generally affiliated with the Rabbits but tried to maintain the black Democrats as an independent force that all the white factions had to court, with results that soon paid off.

Black votes were desperately needed in the early 1920s, as the Democrats sank to one of their lowest ebbs of the 20th century. With the party largely shut out of power in Washington, D.C., and most states, the rural “dry” faction that supported Prohibition was ascendant and heavily infiltrated by the new Ku Klux Klan which added nativism, anti-Catholicism, and anti-Semitism to its roster of hate. Feeling a new sense of potential solidarity with African Americans that temporarily counteracted a long history of racial antagonism, the Irish Catholic-dominated “wets” of the urban wing faced a series of uphill battles.

The 1924 Missouri state Democratic convention “was transformed into a howling mob,” wrote the Star, when Kansas City and St. Louis machine Democrats, led by Tom Pendergast and Joe Shannon personally, tried to insert a platform plank condemning the Klan, only to be defeated by Klan sympathizers from the interior of the state. During the national election that year, the Kansas City Democrats were able to smuggle an anti-Klan statement back into the state Democratic platform during the fall campaign by praising presidential candidate John W. Davis. Their candidate was crushed by Calvin Coolidge in the general election, many Goats and Rabbits lost to Republicans locally, too, but Kansas City had played a crucial role in thwarting the Klan’s political ambitions in Missouri.

The whole experience paved the way for salutary changes by signaling the possibility and indicating the potential utility of an increased reliance on the black vote, even though African Americans were still largely voting Republican. The need for redirection was reflected in the career of young Goat official Harry S. Truman, who may or may not have briefly joined the Klan during his 1922 campaign for the eastern district of the Jackson County court. Truman later ostentatiously prided himself on having quickly rejected the Klan, but with his Confederate family roots and rural Jackson County associations and habits, word on the street in Kansas City touched him with racism. In 1924 the local chapter of the NAACP announced their opposition, and Thompkins focused his attention elsewhere. The “Man from Independence” would learn the hard way to be more careful about his black supporters.

Elsewhere, other members of the Pendergast Machine were learning similar lessons, with Goats, Rabbits, and Republicans all scrambling for black support. As black Republicans grew increasingly restive, the local GOP finally nominated its first black candidate for alderman, Reverend J.W. Hurse of St. Stephen Baptist Church on Independence Ave. Both parties took out ads in The Call, with the Democrats touting their opposition to the Klan and “Police Brutality,” specifically the more-than-rumored use of torture against black suspects: "The Democratic Party is Against Burning Negroes for False Confessions," one ad proclaimed. Meanwhile, Republicans attacked the Democrats for making "our city government the feeding ground of the 'boys,'" including the graft-laden decision to locate a new garbage dump or "swill depot" in a black neighborhood. Hurse lost, but otherwise the Republicans swept the spring municipal elections, and Joe Shannon’s Rabbits were suspected of playing both sides.

Meanwhile, the unpredictable Shannon told reporters about his sudden interest in the Progressive presidential candidacy of Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette and quietly prepared to “knife” his rival Pendergast in the fall county and state elections, selectively abandoning the Democratic ticket, even in favor of Republicans if necessary. Shannon was afraid that the Goats were getting too powerful, and he had experimented in the past with manipulating the black vote to gain advantage. Harry Truman and his fellow Goat on the county court, Henry McElroy, were among the many candidates their knives struck down, although both would soon recover, with the help of the black vote.

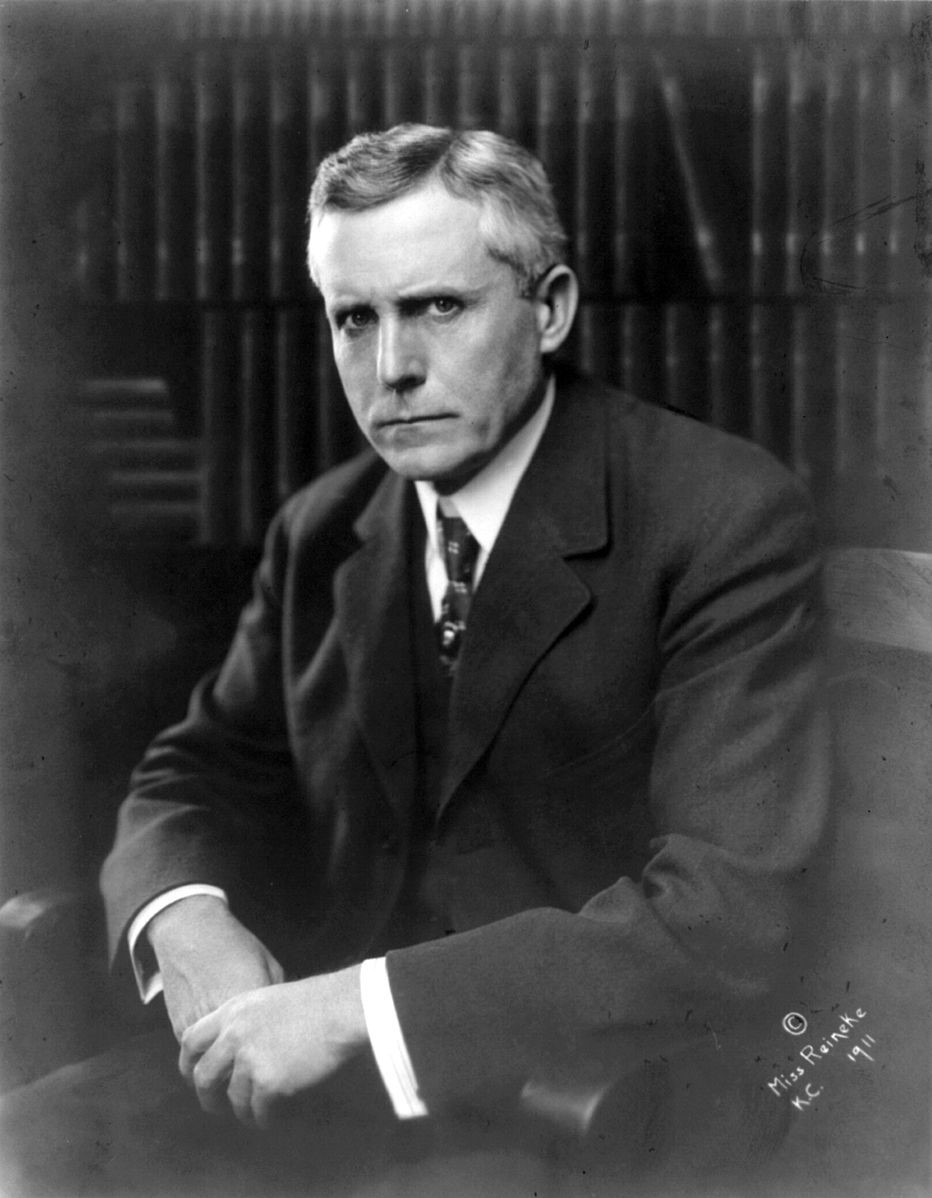

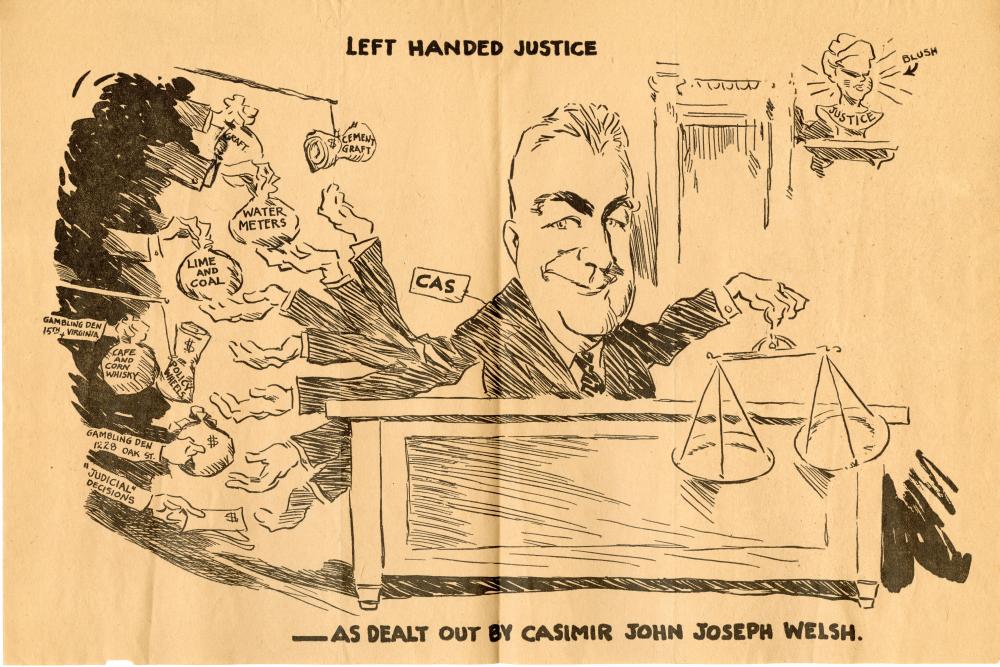

Big Man in Little Tammany: Casimir J. Welch

As the smoke cleared from the 1924 disaster, the black community emerged as Pendergast’s firewall and, to switch metaphors, one of the electoral foundations on which his future would be built. Here we must introduce a new place and character. In between the western Goat and eastern Rabbit bases, geographically and politically, was “Little Tammany,” the bailiwick of Judge Casimir J. Welch and named after the century-old New York City Democratic organization that Welch aspired to emulate. Operated out of a garage at 15th & Troost, Welch’s “Jeffersonian Democratic Club” covered a large swath of the Sixth and Eighth Wards just southeast of downtown Kansas City. One of the most crowded and ethnically and economically diverse sections of the city, its population was sneered at by the Star as comprised “chiefly of rooming house dwellers, manual workers and trade artisans, petty tradesmen and the city’s indigent.” The area also contained the heart of the black business and entertainment district and many black residences of all classes.

A native of this rough-hewn area, "Cas" Welch had been a Rabbit since Joe Shannon picked him out as prime political muscle at age 18. Having already distinguished himself as the toughest newsboy in town, young Cas became an "aggressive and influential member" of the Plumber’s Union. Once outfitted with a politician’s suit and tie, he turned into the most feared political brawler in a town full of them, legendary with his fists and handy with a gun, too. But allegedly the gigantic Cas had a softer side as well. Placed by the machine in a job at the city jail (one of many experiences in common with Boss Tom), he developed a reputation for being sympathetic to people in trouble, establishing a life-long pattern of friendly offices toward ex-convicts and their relatives, of all races, that allowed him to command a ready army of political bodies when needed. One such contingency, and one of Kansas City's less laudable institutions, was the so-called "mob primary," where nominations were made at precinct meetings according to whoever could pack the room with the most people and crowd their opponents out.

For all his frightening and repellent qualities, Welch seems to have been free of overt racial prejudice. Hours of wiretap recordings from the Jeffersonian Democratic Club’s telephone have survived, available to hear at UMKC’s Marr Sound Archives. While Welch and his cronies discuss all sorts of misdeeds their general tone of friendly helpfulness to callers from all walks of life is striking. No ethnic slurs or tensions of any kind are voiced.

In 1910, Welch was elected to his long-term job as justice of the peace and effective boss of the neighborhood he grew up in, putting him in a position to apply the principles of machine politics more directly and bluntly than most. In addition to carrying on the usual charity work, he ran his court as a “justice mill,” where workaday people could deal with their legal problems without need of expensive lawyers and time-consuming procedure. “I’ll be their lawyer. . . justice quick and cheap is my motto,” Welch announced, using his court to build a loyal following among the common people of Little Tammany, including its African Americans. By dispensing local justice benevolently along with food for the poor on a larger-than-usual scale, Welch managed to project a sense of genuine understanding of and pluralistic care for his community.

Working with Thompkins and his friends, Welch developed a significant bloc of black Democratic voters that became one of the bulwarks of Little Tammany. Sincerely believing himself to be a “Friend of the Lowly,” Cas Welch claimed to have “pioneered in the conversion of colored people to the Democratic faith.” Though he ended up living in a Ward Parkway mansion just like Tom Pendergast, Welch was convinced enough by “the Democracy’s” self-image as the party of the lower orders to find it “ridiculous” that blacks ever supported the Republicans. Imagine, he told a reporter, “the very poorest people in the nation voting to perpetuate in power the wealthy people who keep them poor!”

In the fall elections that year, horrified by the duplicity of Shannon, Welch defected to Pendergast and the Goats, ordering his followers to vote the straight Democratic ticket, no matter what his old mentor said. Thompkins and other prominent black Democrats followed suit. This turned out to be the best move of Welch’s life, soon elevating him to number two man in a rejuvenated Pendergast Machine that increasingly relied on his long-time strategy of forging good relations with the black community. With Republicans riding high in the outlying precincts, the east side Rabbits were not much without Little Tammany, and after 1924, Joe Shannon’s days as a serious rival to Tom Pendergast were over. He began to take a deeper interest in making historical speeches about Thomas Jefferson than contesting his old turf and soon got elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Welch argued that he made the bold departure of trying to serve the interests of his black constituents. “In the past the Republicans showed some consideration for the Negroes on election day—usually $2, $3, or $5, and at times as much as $10,” Welch recalled. (He had been known for personally handing out liquor and cigars on 18th Street, as well as money.) “We Democrats hit upon the idea of doing something for the Negroes every day of the year.” Paternalistic as it was, the Welch formula amounted to a more liberal and tolerant set of social policies.

Welch's focus was on getting indigent and struggling blacks food, fuel, and basic employment, legal or illegal, but otherwise letting them let them live their lives without supervisory interference, except at election time. In return for electoral support, the government would help provide black neighborhoods with access to better public health, educational, and recreation services and afford them less brutal and unfair treatment from the police and the courts.

African American Votes, the Kansas City Machine, and the "New Abolition"

"Machine Smashed! Home Owners Win! Hogpens Are Not Wanted," trumpeted the Star the morning after the 1924 elections, and indeed, with Republicans controlling the state, county, and city, the forces of Republican retrenchment and reform seemed to be in the driver’s seat. Immediately, in 1925, they were finally able to get their long-planned new City Charter approved, with a small (9-member) unicameral city council, a weak mayor, and most power vested in a professional city manager appointed by the council. But with Welch now in his camp, and a smaller number of geographically consolidated wards, including most of Little Tammany, packed into the new Second Ward, Pendergast found it child’s play to get his men elected to five seats on the council and control it immediately.

One of the defeated Goats on the county court, Henry McElroy, was rapidly installed as city manager, in which capacity his “country bookkeeping” would allow the machine to rake off millions from city operations while executing a massive modernization program and still, according to McElroy, remain in the pink of fiscal health. The other defeated Goat judge, Harry Truman, was duly restored to his seat on the county court in 1926, and led much of the building program. Even though the finances behind it all turned out to be a lie, the illusion of prosperity kept the Pendergast machine and Kansas City politically afloat for much of the Great Depression.

Building up what they hoped would be a permanent majority in the city and county took more time, but a major part of the project was increasing the Democratic black vote. Control of the city government and its revenue streams left the machine so flush with cash that it immediately invested in political tools they hoped would increase their influence in the state and nation, while expanding and consolidating it at home. The media was a major target. The city’s most widely read black and white newspapers, The Call and the Star, were Republican-oriented and inveterate enemies of the machine. Tom was from the old school of American politics that said your political movement was nothing if it did not have a newspaper to represent your community and tell your story to your supporters. He paid for a new journal, the aptly named Missouri Democrat, with daily and weekly editions edited by one of his right-hand men, county chairman Jim Aylward.

Approaching the presidential election of 1928, the Pendergast machine invested in another newspaper project, this one aimed at furthering the “great switch” of Kansas City’s black voters from the party of Lincoln to the party of Jefferson. This was the Kansas City American, a black Democratic newspaper (published by William Thompkins) that would compete directly with The Call. The American's take on most substantive issues was not that different from Franklin’s The Call, but in politics it embraced Thompkins’s vehement conviction that blacks could only find true political independence and equality outside the Republican Party, where they were the inferior partner in a servile relationship.

Inside the Democratic Party, the American argued, African Americans could join the broad category of “the people” whose rights would be equally protected. This claim went far beyond the available facts or reasonable predictions, but at least northern urban Democrats saw blacks as an interest group to be courted. “LIBERTY vs. INTOLERANCE Which Shall it Be? Don’t Be a Political Slave! Vote the Democratic Ticket Straight!!!” shouted one of the American’s campaign display ads.

That slogan reads quite oddly today and was somewhat belied by the limited, double-edged benefits Kansas City blacks would actually receive from the Pendergast machine and the New Deal. Pendergast helped make Kansas City a cultural mecca for blacks that afforded more opportunities to pursue creative careers, live freely, and work more lucratively than would have been available otherwise, but those opportunities came at the cost of turning the heart of the main black business and residential district into a 24-hour vice and entertainment center, with heavy Mafia influence and accompanying violence. Nonetheless, the effort made after 1925 to carve out a space for African Americans in the Kansas City Democratic Party was very serious, and partly reflected in the American itself, which was believed in Missouri to be the only explicitly Democratic black newspaper in the country for much of its existence.

The occasion for the American’s appearance was the tremendous opportunity that arose for Missouri Democrats to make inroads with black voters as the Republican Party prepared to hold its 1928 national convention in Kansas City. With huge majorities of Klan-curious middle-class Protestant whites behind them, the Republicans showed decreasing interest in maintaining the allegiance of black voters throughout the 1920s. Presidents Harding and Coolidge appointed fewer blacks to office than even southern-born Democrat Woodrow Wilson, and segregation was imposed in federal departments where it had not even existed before. Then Herbert Hoover, the favorite for the 1928 nomination, decided on the GOP’s first “southern strategy,” looking to acquire more white and dry votes in the South. At the convention—hosted in Kansas City—the local housing arrangements committee voted to bar black delegates from the convention hotels, and that was if they were allowed to attend at all.

The American jumped immediately and vociferously into the Democratic campaign, putting out a daily edition during the party’s convention in Houston and then actively supporting the party’s Irish Catholic nominee, Governor Al Smith of New York, in the fall. Making an analogy between anti-Catholic bigotry and the racial kind, and seizing on Republican race-baiting of Smith for the relatively integrated conditions in his home state, the American depicted Smith as the “embodiment of true Americanism” and a patriotism that was “Non-Racial, Non-Sectarian.” William Thompkins became one of the most prominent organizers of a black “Smith for President” league, but while most of the black political elite and press endorsed Smith, they stuck with the Republican Party in other contexts, and the doomed Smith campaign failed to capitalize.

In Kansas City, Democrats’ courting of the black vote paid off locally despite the national Republican landslide. Thompkins boasted that he had pushed the Democratic percentage of the black vote in Kansas City up to 47 percent, nearly twice what it had been in 1924. In 1930, with the Depression and a new black hospital opened, the Kansas City Democrats made electoral breakthroughs with the black community and the wider public that would build up quickly in subsequent elections. This was a nationwide change, but Kansas City was a leader. Thompkins traveled the country for Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as he had for Davis and Smith. He claimed that the black vote had been a key to tipping the election to Roosevelt throughout the Midwest, telling an audience in Omaha after the election that the Democratic victory amounted to a “new abolition.”

According to modern scholars, this change was just getting started in most localities, with Hoover still pulling 70 percent or more of the black vote in Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Philadelphia, and the most pronounced shift visible only in 1936. In contrast, the American bragged about a 70 percent black vote for the Democrats in 1930, and Cas Welch claimed to have 80 percent of his black precincts voting Democratic by 1934.

Unfortunately, one of the methods Welch and the Democrats used to accomplish this precocious feat at the polls was manufacturing votes, not just in the usual sense of boosting turnout with money and liquor, but by inflating precinct totals with ghost votes. Welch, Roosevelt, and the Democrats were undoubtedly popular in Little Tammany, but the total vote in the area mysteriously almost doubled every election from 1928 to 1936 (when Welch died), despite generally flat population numbers. By one estimate, the Second Ward may have generated as many 15,000 ghost votes. On the wiretaps, even Welch admitted that he went considerably further than he needed to win.

Whatever their means of winning, the Pendergast machine actually did try to deliver for the constituencies within the limits of their control and self-interestedness. The Democrats’ most popular move in Little Tammany and the North Side, where much of the black population lived, and where most of the Italian, Irish, Jewish, and African American gangsters operated, was gaining “home rule” for the police, which was still controlled by Republican officials out of Jefferson City. The most serious issue in the black community was violent, arbitrary, and excessive policing that seemed to disproportionately target African Americans and their neighborhoods. Tom Pendergast and Cas Welch were prepared to do something about this, for both good reasons and worse ones, stemming from their growing alliance with organized crime. The Democrats hit the issue especially hard in the 1930 city elections, in which they took back the mayor’s office. The American’s pre-election headlines included such on-message items as “Cripple Brutally Assaulted by K.C. Police” and “Police Torture Chamber Revealed to Citizens.”

In the near term, home rule allowed the Democrats to end the rampage of Republican-appointed police chief John L. Miles. Miles’s manic enforcement of country Protestant values (in the form of Prohibition and anti-gambling laws) in black and Catholic neighborhoods resulted in more than 100 raids on the East Side Musicians’ Club, along with many other depredations, some comic and some very much not. As even the Republican Call admitted, the machine’s replacement, Police Director Eugene C. Reppert, at least temporarily put an end to the “reign of police brutality.” Yet the Pendergast Democrats also allowed their criminal allies to take control of the police—local Mafia boss Johnny Lazia was reputed to be “one of three who had voice in naming” officers—and to operate for a few years with a disastrous impunity that eventually ruined everything: the political machine, jazz clubs, and all.

Harry Truman’s Escape from Goathood

While we often think of the modern Democratic Party as the creation of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the real origins of the “New Deal coalition,” as it survived past the 1930s, can be found in the Kansas City politics of Harry S. Truman. The parts of the New Deal agenda that were consolidated and expanded were those preferred by border south Democrats generally and Truman personally, while the aspects they rejected were abandoned or faded in importance. Hence, the New Deal’s experiments in cartelization and direct relief were retrenched and abandoned rather quickly, under the glares of Jeffersonian penny-pinchers who included Truman, Joe Shannon, and their myriad southern segregationist friends in Congress. At the same time, New Deal programs like Social Security that aimed to prevent people from falling out of the lower middle classes got much warmer support and were even expanded.

Truman won his first Senate race in 1934 as Pendergast’s man, with the machine’s power, corruption and violence at its apex. In 1940, with Pendergast in jail, Welch dead, the gambling dens and brothels no longer tolerated, and the jazz scene a memory, Senator Truman stood fair to be Pendergast’s Goat, literally and figuratively. He faced opposition in the Democratic primary from the two men who had done the most to bring Pendergast down, Governor Lloyd Stark and prosecutor Maurice Milligan. Determined to win while remaining loyal to his old chieftain, Truman took the advice and possibly the speechwriting help of William Thompkins and made a strikingly bold play for the black vote that he realized held the key to his surviving the primary. His opponents had left a wide opening. Few of Tom Pendergast’s pursuers had ever been especially friendly to the state’s urban black communities.

Truman chose the small rural metropolis of Sedalia, home of the Missouri State Fair, to officially open his campaign on July 15, 1940. In a speech that his campaign touted as an historic event, Truman staked his claim to the strongest New Deal record of the three major candidates by making a speech that was for that time and place, and for a politician of white southern ancestry, a radical endorsement of truly equal opportunity and citizenship for African Americans, tied directly to their history of oppression and re-oppression in his home region:

I believe in the brotherhood of man; not merely the brotherhood of white men, but the brotherhood of all men before law . . . . In giving to the Negroes the rights that are theirs, we are only acting in accord with our ideals of a true democracy. If any class or race can be permanently set apart from, or pushed down below, the rest in political and civil rights, so may any other class or race . . . and we may say farewell to the principles on which we count our safety.

By announcing himself as Missouri's great champion of civil rights, Truman could both step out ahead of the New Deal and avoid the short-term reverses it was suffering in 1940. Roosevelt won reelection, but his liberal Republican opponent, Wendell Willkie, cut down FDR’s margins considerably, partly by appealing to black voters (especially black elites) more than any Republican candidate had for a generation. The local situation in Missouri was far worse. Increasingly dissatisfied with the crumbs of patronage, policy, and funding that the New Deal regime had allowed them, black and working-class white voters sent Democratic gubernatorial candidate Larry McDaniel and many others down to narrow defeats in 1940. Harry Truman, on the other hand, not only beat Stark and Milligan in the primary, but also ran more than 20,000 votes ahead of McDaniel in the general election and won. The nature of the Democratic Party’s relationship with African Americans, especially the sincerity of its claims to serve the interests of black voters, remains a debatable question, but the messy mix that defines that relationship—of self-interest, corruption, and self-deception, along with genuine sympathy and the rejection of hate—had one of its major formative moments in Kansas City.

Funding for this essay is generously provided by the Missouri Humanities Council with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

A longer version of this article is published in the book, Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era (University Press of Kansas, 2018), edited by Diane Mutti Burke, Jason Roe, and John Herron.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.