The Call Newspaper

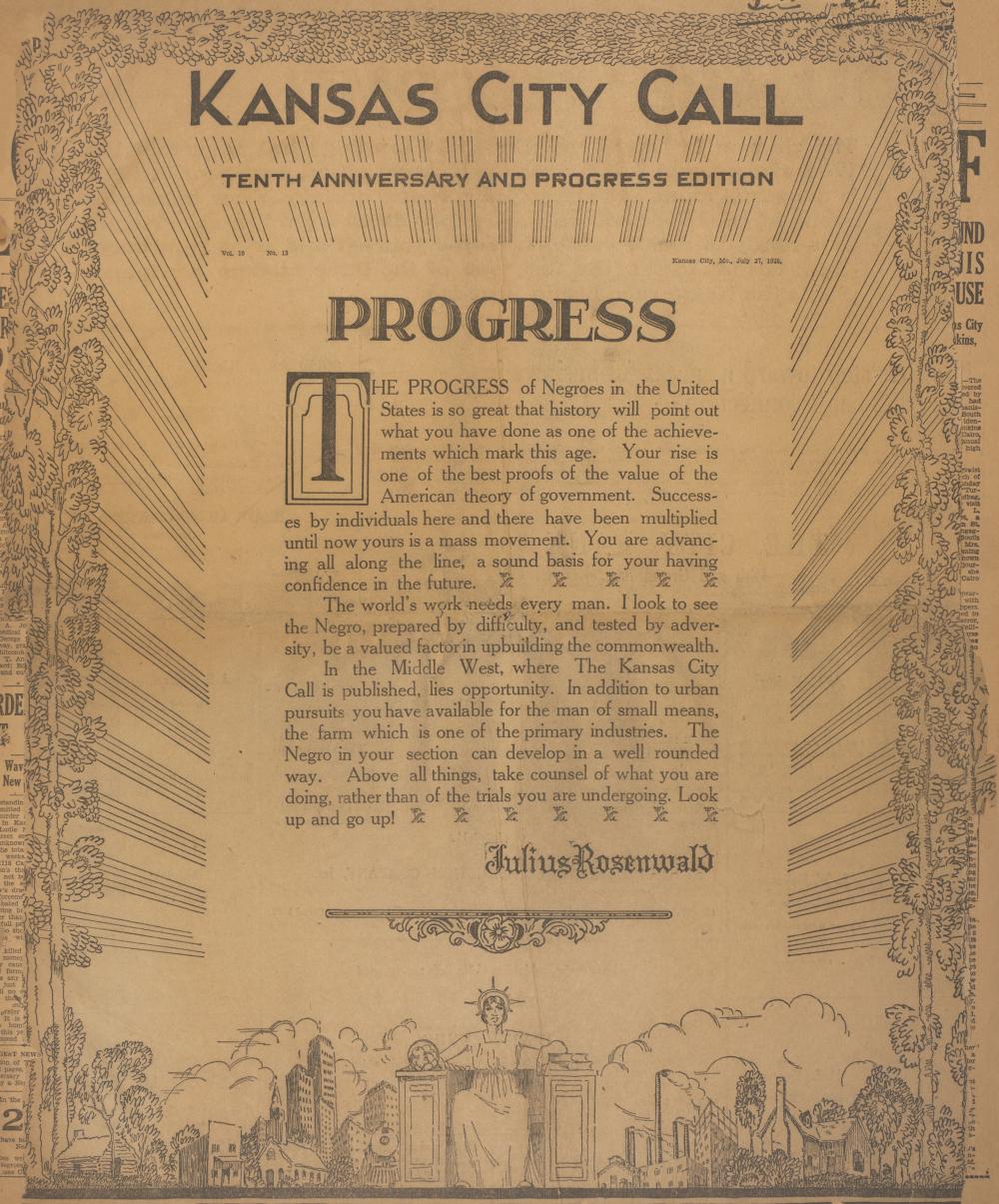

The first edition of the Kansas City Call or The Call, was published on May 6, 1919. It was one of 22 newspapers published by Kansas City’s African American community near the beginning of the 20th century, but the only one that survived past 1943. Starting as an inauspicious four-page paper, the paper soon grew to one of the most successful black newspapers in the nation.

The Call’s founder, Chester Arthur Franklin, was born in 1880 in Denison, Texas. He moved with his family to Omaha, Nebraska, in 1887, where his father founded the Omaha Enterprise newspaper to advocate for blacks in Omaha. Just two years later, his father’s health declined and the family moved to Colorado on the advice of doctors who thought the climate might improve his condition. Once there, the Franklins purchased another black newspaper, the Star. By the time Chester’s father died in 1901, Chester and his mother, Clara Franklin, were already successfully running that newspaper themselves.

By 1913 Chester Franklin had gained considerable experience in the newspaper business, but he wanted to reach a broader audience. He moved to Kansas City, which had a larger black population, and entered into the printing business until he could gain the resources and local reputation required to open another newspaper. On May 6, 1919, he finally founded the The Call, which he would own and edit until his death in 1955.

The new business resided at 1311 East 18th St. in a small 800-square foot building. Under Franklin’s leadership, The Call served as more than a news source for the black community. It advocated for equality and served as the most tangible public voice of the black community. In 1922, The Call’s success already necessitated a new, larger building that was located at 1715 East 18th St.

The newspaper especially thrived after it hired reporter Roy Wilkins in 1923. Wilkins, who would later become the executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1955, provided thought-provoking articles for The Call in his regular column, “Talking It Over.” The paper came to rival one of the nation’s most eminent black newspapers, The Chicago Defender.

In the 1920s and 1930s The Call helped the African American community win several local battles for civil rights. Blacks gained the right to serve on juries in Kansas City. Segregation laws in employment and housing were reduced, although not defeated outright. In one case, Wilkins and The Call led boycotts against a bakery that resulted in the hiring of black truck drivers. A more controversial, but persistent, message in The Call advocated a reduction of violence within the black community. A political conservative at heart, Franklin believed strongly that the black community needed to focus on its internal issues as much as equal legal rights.

When Chester Franklin died in 1955, his wife, Ada Franklin, and another editor, Lucile Bluford, a graduate of the University of Kansas with a degree in journalism, took over the paper and continued its legacy. The newspaper remained among the six most widely circulated black newspapers in the nation. Today The Call still advocates in the interests of the African American community from the 18th Street location that Chester Franklin purchased in 1922.

A previous version of this article is published on kchistory.org: http://www.kchistory.org/week-kansas-city-history/heeding-call

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.