Our Time to Shine: The 1928 Republican National Convention and Kansas City’s Rising Profile

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Kansas City experienced a profound period of transformation. Its centralized location and bucolic natural beauty drew new residents and businesses that invigorated the city. Optimism surrounding recent growth and municipal development, however, was tempered by knfowledge that regional rivals were experiencing similar expansion. City leaders worked continuously to sustain forward momentum through ongoing urban planning, infrastructure projects, and continuous efforts to increase the city’s national profile.

According to a May 29, 1928, editorial in the Kansas Citian (a newsletter published by the Kansas City Chamber of Commerce), the Republican National Convention promised to “bring more influential people in industry, business, and financial circles than ever brought here by a convention.” Local leaders envisioned the 1928 Republican National Convention raising the national and regional profile of Kansas City in two related ways. First, delegates and visitors attending the convention could see the city’s growth in person. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the event and subsequent attention would bolster the city’s standing, particularly in relation to regional rivals such as Cleveland and St. Louis.

Ultimately, the plan worked. Efforts to organize and host a national political event energized Chamber of Commerce leaders and united Kansas Citians behind efforts to improve their city. Goodwill generated by the convention galvanized support for a comprehensive, strategic Ten-Year Plan, which spurred municipal improvements, modernized facilities, and positioned Kansas City for success in the 20th century.

Envisioning Growth

The 1928 Republican National Convention followed two distinct periods of municipal growth in Kansas City. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, multiple efforts had been made to direct development towards aesthetically pleasing and commercially viable goals. Architect George Kessler, along with the Commercial Club, forerunner of the Chamber of Commerce, laid the foundation for Kansas City’s park system during the City Beautiful Movement. Their efforts, according to historian William H.Wilson, “remade an ugly boom town [Kansas City], giving it miles of graceful boulevards and parkways flanked by desirable residential sections [and] acres of ruggedly beautiful parkland dotted with recreational improvements.”

As the momentum behind the City Beautiful Movement ebbed, the restructured Chamber of Commerce played an increasingly prominent role in municipal improvement projects. During the early 1920s, the Get-it-Done campaign updated Kansas City’s infrastructure without the help of bond financing. The effort included rerouted streets, new bridges, and widened thoroughfares. When the campaign ran up against financing limits, however, progress stalled. By the mid- to late 1920s, calls had begun for a renewed and systematic approach to municipal improvement. In 1926 a chamber subcommittee argued, “Kansas City has arrived at a point where if it is to maintain its position and prestige with other cities that are in keen competition with it and fighting for commercial supremacy, it must do more than it has been doing.” The group recommended “advertis[ing] Kansas City in a nation-wide way” and implored the business community to unite behind a plan that would keep pace with regional rivals.

A month before Republicans gathered in Kansas City, a May 1928 special election placed multiple bonds before voters. The Citizens’ Bond Committee, “[r]epresenting nearly 100 civic, labor, and business groups,” distributed a 23-page booklet in favor of the proposed improvements. The city’s leading African American newspaper, The Call, also urged its readers to support growth. An editorial from April 13 argued, “the bulk of all public expenditures goes for labor. Readers of The Call, being almost wholly of the laboring class, will feel the increased demand for labor at once.”

Unfortunately, most initiatives failed. The Kansas Citian observed many projects received over 60 percent voter support, but only “the Municipal Wharf, Swope Park, the County Hospital, and the County Highway System overcame the constitutional requirement of a two-thirds majority.” The Call’s editor, Chester Arthur Franklin, lamented, “Kansas City might as well go to sleep, letting the grass in breaks in the pavement be the only thing at work. The old Kansas City spirit is sadly in need of repair.”

Despite the failure of recent ballot initiatives, city leaders remained committed to pursuing municipal improvements. In fact, the waning enthusiasm for bond measures directly contributed to their desire to host the Republican National Convention. Many within Kansas City’s business community viewed the event as a springboard for promoting Kansas City to regional and national audiences. Further, they believed that the event would bolster residents’ civic pride. The success of the event in 1928 provided a pivotal injection of optimism regarding Kansas City’s future. Many of the projects which were later realized through the Ten-Year Plan preceded the convention, and a framework for implementing infrastructure initiatives already existed prior to the event. But without the public unity inspired by the Republican gathering, Kansas Citians might not have ultimately rallied behind the Ten-Year Plan.

A Bipartisan Effort

When Kansas City decided to stake a claim for the 1928 convention, community leaders balanced ambition against likely disappointment. By early 1927 the Democrats had already selected Houston, and Chamber of Commerce minutes indicate that many members believed the Republicans were “all fixed to go to Cleveland.” Nevertheless, it was decided “as a matter of policy and publicity” that Kansas City should volunteer as convention host. Republicans and Democrats in Kansas City, with national exposure and potential prosperity in mind, put aside political differences to unite behind the convention effort. In late 1927, Robert H. Tschudy, Chairman of the Republican County and Congressional Committee in Kansas City, wrote that the process of securing the convention “has become a civic matter.” Tschudy extended “to those members of the Democratic party its appreciation for their cooperation in this movement which will be of such wonderful financial and advertising value to the city as a whole.”

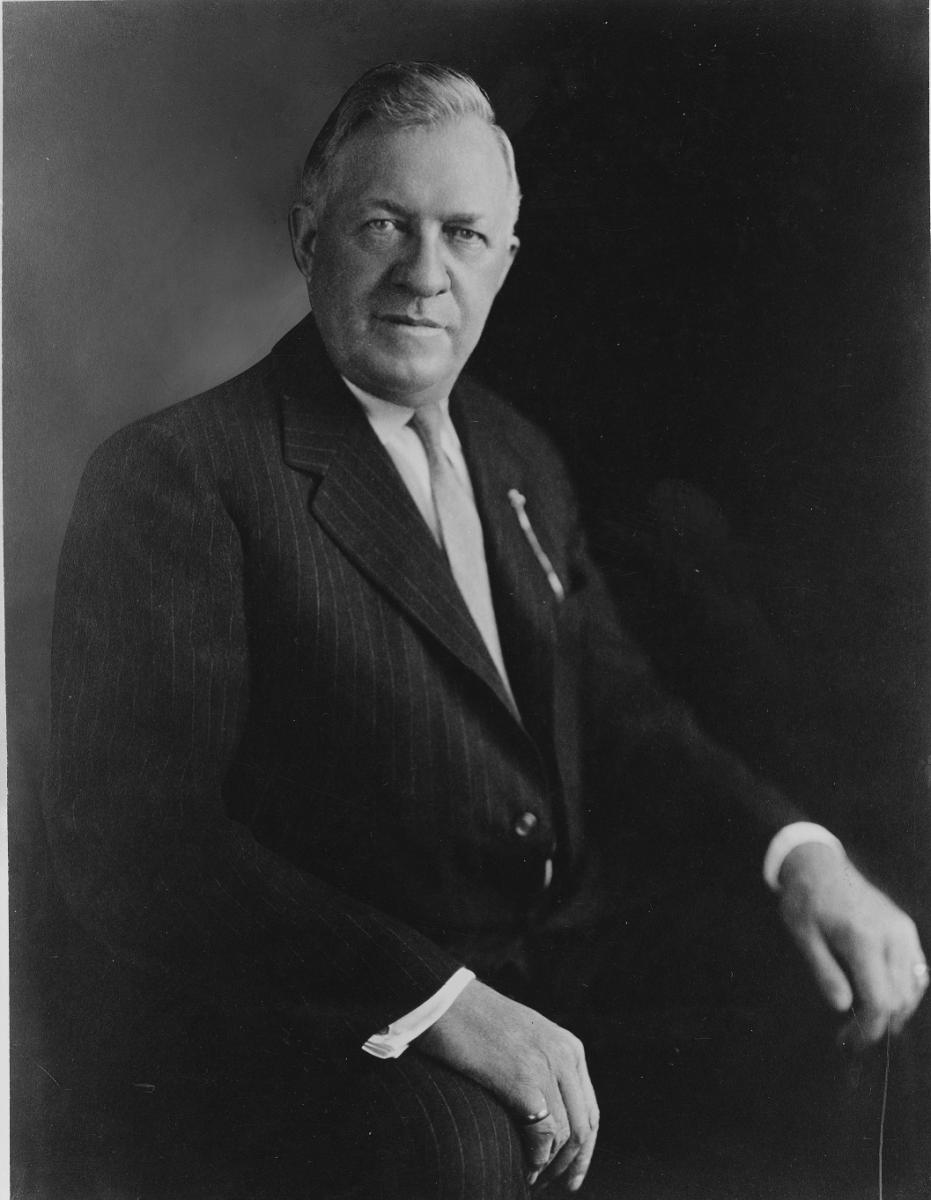

Bi-partisan support for the 1928 convention continued through the June meeting. Republican Mayor Albert Beach and his predecessor, Democrat Frank Cromwell, served on the general executive committee along with Democratic politicians Harry Truman and current city manager Henry F. McElroy. In addition, the staunchly Democratic Jouett Shouse served on the general executive committee and headed the publicity committee. Lurking just below the carefully maintained outward façade was the Pendergast machine. Multiple individuals and groups that supported efforts to secure the convention had well-established ties to the organization. Consequently, their involvement demonstrates how the Pendergast machine clandestinely endorsed the effort and ensured itself a portion of the economic benefits once the Republicans selected Kansas City. Ultimately, the widespread commitment of Kansas City’s business and commercial class demonstrates that civic boosterism and a capitalistic self-interest, rather than partisan ambition, motivated support for the 1928 gathering.

When Kansas City was announced as the host for the 1928 Republican National Convention, it marked a culmination of an intense lobbying campaign on behalf of the local business community. Political concerns, especially the ongoing agrarian depression, also made Kansas City an appealing choice for Republican leaders. A full-page story in the New York Times Magazine explained, “if the convention were to be a mere ratification meeting, such as that at Cleveland four years ago . . . San Francisco or some city on either ocean would be suitable.”

Recent events, however, demanded a centralized party gathering in “Kansas City . . . on the very edge of the great open spaces where men are men and Republican farmers are discontents.” By choosing Kansas City as their convention site, the paper argued, Republicans demonstrated they were “not under the domination of those effete Eastern industrialists and financiers whose hearts are supposed to be cold to the desire of the embattled farmers of the West.”

The convergence of national politics and a local economy dependent on stockyard and regional farm production contributed to numerous public marches and vocal demonstrations during the summer gathering. In addition, ongoing agitation on the convention floor reinforced the power of agrarian issues to energize potential voters and influence the nomination process. Though Kansas City might not have been the Republicans’ choice during boom times, the combination of direct solicitation, local organization, and historical circumstance provided the city a unique opportunity. City leaders were determined to use the national spotlight to promote Kansas City’s transformation and potential for future growth.

Championing Kansas City

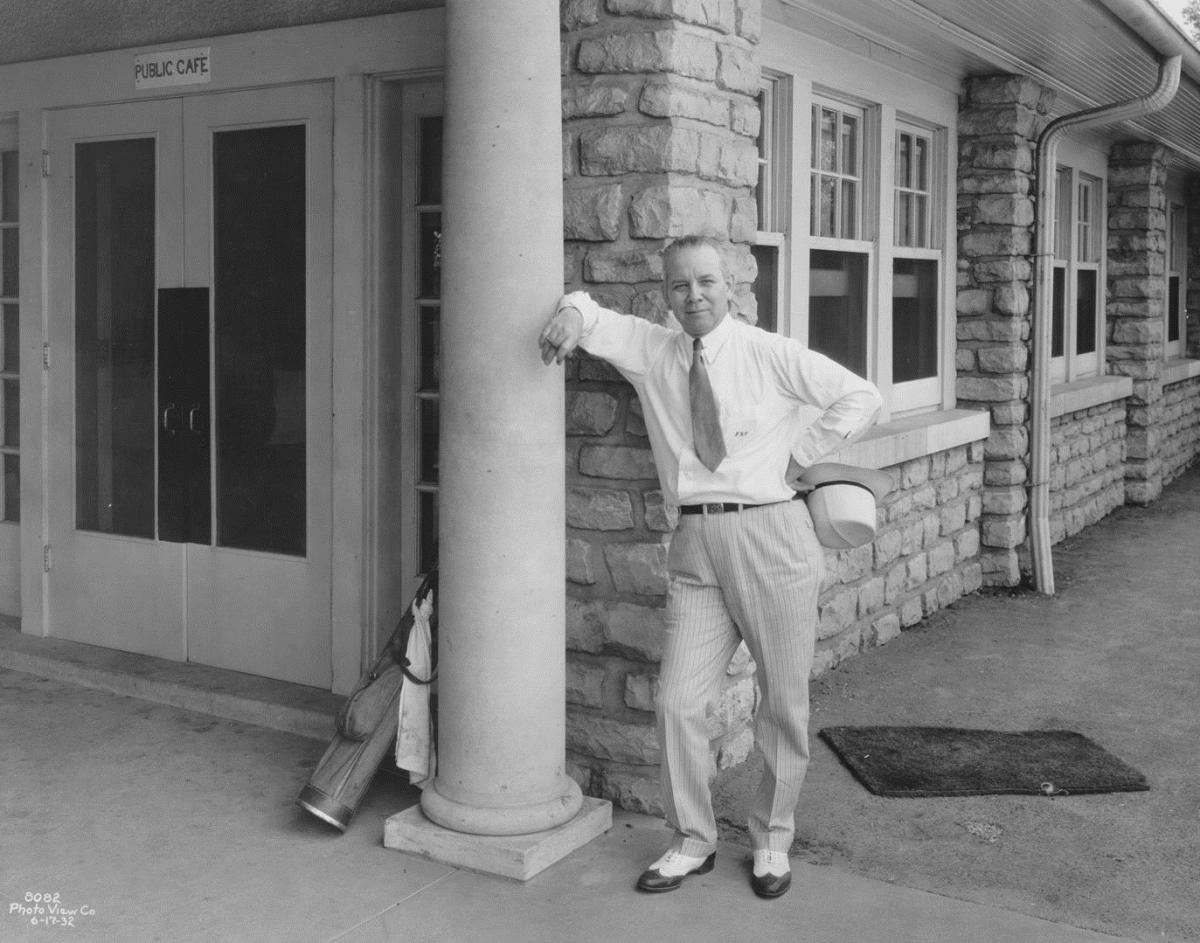

The Chamber of Commerce created a vast organizational structure to prepare Kansas City for the national spotlight. The General Executive, Finance, and Arrangement Committee oversaw all convention planning. Thirteen standing committees, plus additional subcommittees, were also created. Leadership positions were filled by many individuals who had vigorously campaigned during the spring of 1928 for the recently failed ballot initiatives. Conrad Mann, Frank Dean, and Max Dyer, for example, had served on the Municipal Bond Committee, and each held key positions during the Republican convention. Mann served as General Chairman for the Republican National Convention Committee, while both Dean and Dyer were members of the Executive Committee. Dean also served on the Transportation and Housing Committees.

The publicity committee served perhaps the most important convention function. Under the leadership of Jouett Shouse, the publicity committee oversaw pre-convention promotion and distributed positive press releases to journalists across the country. These efforts served two purposes: first, they created a sense of anticipation among delegates and journalists covering the convention. Second, and perhaps most important, the stories used the convention to reach individuals who might never have thought about Kansas City as either a tourist destination or as a viable commercial hub.

At the request of the National Republican Committee, Shouse’s committee compiled The Book of the Republican National Convention. Focused primarily on the summer gathering, the publication included “all possible pertinent information relative to the Convention itself and its personnel.” There was also a “full history of the Republican Party.” Interspersed between party history and advertisements, which publicized both local businesses and national and regional enterprises with branches in Kansas City, were articles touting the city’s character. An article headlined “Heart of America,” for example, explained that geographic location made Kansas City “the central storehouse and distributing point for a vast domain.” Consequently, Kansas City boasted “manufactories for conversion into consumable form the countless products which have been so extensively developed in the great southwest” and served as the crossroads for a flow of products. Specifically mentioned were “livestock, grain, oil, [and] lumber [that] made this territory a veritable empire.”

The Book of the Republican National Convention attributed Kansas City’s character to “a small group of recognized leaders,” including City Beautiful architect George Kessler, who uncovered “the aesthetic possibilities contained in the peculiar topography.” Photographs highlighted many landmarks and parks established by the City Beautiful Movement. Emphasis on natural beauty continued in a section labeled “Residential Districts of Charm.” Visitors were told that Kansas City’s “residential sections partake of the aspects of immense gardens and fit, without break or jar, into the delightful irregularities of its charmingly rugged topography.” The design and development reflected the vision of “the original planners of this ‘city beautiful.’”

Published in June 1928, The Book of the Republican National Convention did not influence the party’s site selection. It did, however, promote Kansas City’s commercial advantages and residential appeal to visiting politicians, operatives, and reporters. City leaders hoped a positive convention experience might lure new residents and investment to Kansas City. Similarly, civic pride and economic incentive spurred businesses to advertise within the publication in hopes of reaching customers and future connections during the event.

Welcome to Kansas City

Kansas City residents worked diligently to create a festive convention atmosphere. The Kansas City Star reported that flags, bunting, and other adornments enlivened streets surrounding Convention Hall. Local businesses used over 300,000 brightly colored stickers bearing convention dates and a GOP elephant on outgoing mail. Members of the Hosts and Hostesses Committee, stationed in various convention hotels, “furnished information concerning the whereabouts of places of meetings and points of interest in the city.” William Morton urged “a friendly and gracious manner” among the “approximately twelve hundred men and women enlisted in this particular assignment.” He reminded volunteers that the goal is to ensure “our guests will leave Kansas City fully convinced that we are in deed and in spirit the ‘Heart of America.’” Individuals unable to serve as a host or hostess could volunteer as an auto tour driver. Organizers solicited vehicles and volunteers, reminding residents, “This is a Kansas City proposition. Not necessary to be a Republican to serve on this committee. Your car will be needed.”

As delegates and attendees arrived, convention organizers provided a Visitor’s Guide to Kansas City that served as an introduction for those traveling during the summer of 1928. With less focus on the Republican Party and convention history, the Visitor’s Guide to Kansas City highlighted the city’s geographic advantages and municipal amenities. Additionally, during the summer of 1928, the Kansas City Hotel Greeters’ Association promoted Kansas City tourism through the Greeters’ Guide to Kansas City. This document introduced visitors to Kansas City’s frontier past and progression “from a trading post . . . [to] a lively and hustling metropolis.” Simultaneously positioned as “gateway to the west” and “heart of America,” the Greeters’ Guide proclaimed, “[Kansas City] offers two things preeminently American: the outstretched hand of hospitality . . . and the key to the greatest gift of all, boundless opportunity.”

Beyond introducing the city’s cultural heritage, the Greeter’s Guide also called visitors’ attention to the enhanced natural beauty found in Kansas City. Short descriptions of major attractions were followed by auto-tour options, ranging from a 45-minute trip to a three-hour tour, which highlighted Kansas City’s neighborhoods and park system. Finally, the publication represented an ideal venue for local businesses to reach out-of-town visitors. Thirteen theaters were listed along with both full and partial page advertisements for all manner of Kansas City businesses. Lodging and transportation options could be found by perusing the advertisements of 32 hotels, three bus lines, and four car services. In addition, the guide touted retail shopping and vital resources for someone moving to Kansas City, such as hardware stores, banks, and utility providers.

While the Book of the Republican National Convention targeted delegates and convention attendees, both the Visitor’s Guide to Kansas City and Hotel Greeter’s Guide marketed the city to everyone. The commercial content and coordination of the latter publications represents the broader campaign to highlight the benefits of visiting and living in Kansas City. Collectively all three texts demonstrate a commitment by convention organizers to entice delegates and attendees to leave the convention floor and experience Kansas City, using the occasion as a springboard for future municipal growth.

Race and the Convention

While Chamber of Commerce leaders hoped to bring positive publicity to Kansas City, controversy erupted regarding the role of African American delegates and attendees. Despite the racial integration of previous conventions—both Chicago and Cleveland seated African American delegates alongside all attendees and assigned them lodging within the same hotels as white delegates—Kansas City maintained a rigid color line. The decision enflamed the editors of The Call. Multiple articles and editorials vehemently condemned convention organizers, particularly Conrad Mann, and lambasted enforced segregation.

Mann justified convention segregation as consistent Kansas City policy. He explained, “[o]ur Negro population would have cause to reprove us if we accorded any different treatment to visiting Negroes, merely because they happen to be in Kansas City.” Convention organizers, however, added three black members to the Executive Committee in an attempt to mollify African Americans. They also established a separate Negro Entertainment Committee. A venue for the entertainment of black delegates and attendees was located at 13th and Paseo.

Delegate segregation reverberated beyond Kansas City. On a national level, it marked a strategic decision by the Hoover campaign. In order to appease southern voters, Republicans avoided appearing too radical on questions of racial equality and civil rights. Chester Franklin labeled the lack of attention paid to race issues in the 1928 platform, “a sorry crumb.” Negative publicity in outlets ranging from the New York Times to the Chicago Defender undercut efforts of convention organizers to showcase Kansas City’s unity. Delegate segregation in Kansas City also created an opportunity for Democrats who sought to sever the link between black voters and the Republican Party.

The 1928 Republican National Convention laid bare internal tension among Kansas City’s black residents. Franklin’s condemnation of delegate segregation and the public actions of convention organizers during the summer of 1928 foreshadowed a long-term shift in his overall conservative approach to community leadership and activism. Nevertheless, he remained an advocate for Kansas City’s future. Not all African Americans, however, supported Kansas City’s leaders. One reader of The Call proclaimed, “[it] is time that we call a halt on our ballots, tell our leaders either to stiffen their backbones or step out.” The author reasoned, “The national convention in coming to Kansas City let the local committee ignore the constitution in segregation and discriminating the delegates of our race.” Yet, local “leaders knowing full well these facts accept a handful of decorations on East Twelfth street, Eighteenth street, as a salve then place a button in the lapel of their coat and come to plead with the race to have confidence in you and to vote for the man or men you stand for.”

Four years before Republicans gathered in Kansas City’s Convention Hall, the venue hosted a major gathering of Ku Klux Klan leaders in a national convention. These events, though unrelated, demonstrate competing impulses which characterized Kansas City during the 1920s. For African American activists, the persistent racist attitude of some Kansas Citians and citywide discrimination emphasized the need for comprehensive reform. Elected officials and businessmen within Kansas City, eager to end lingering provincialism, sought to expand the city’s influence and implement municipal improvements. They were, however, dependent upon all Kansas Citians for political and economic support. As a result, the controversy which erupted during the Republican National Convention epitomizes city leaders’ ongoing struggle to please both constituencies and move Kansas City forward.

Forward Momentum

Following the 1928 convention, reporters from over 50 publications issued a collective statement of praise. The New York Times Magazine noted, “Missouri’s ‘Gateway to the West’ has grown up since the Democrats Went there in 1900.” The editorial page of the Dallas Herald observed, “We didn’t think Kansas City could take care of such a large gathering . . . I have found our fears groundless. I was never as well taken care of as now. The tremendous hospitality of the people of Kansas City is equaled only by the life and energy of the people.”

The 1928 Republican National Convention also generated enormous civic pride among Kansas Citians and strengthened a cadre of leaders within the Chamber of Commerce. Consequently, the event reinvigorated support for municipal improvement. In the weeks after the convention, Chester Franklin urged readers of The Call to support upcoming initiatives to improve the airport, water works, and streets. Franklin argued:

City improvements . . . are the city’s housekeeping, which invites or repels prospective business enterprises, in search of better location. These give preference to cities which offer the best surroundings for labor, and the best facilities for commerce. Kansas City has natural advantages. But it must develop them, or be counted out as a good place to live and do business.

To ensure broad citywide support and avoid the failed ballot results of the previous year, Conrad Mann spearheaded a Civic Improvement Committee. Unlike the segregated planning committees in place during the Republican National Convention, African American members were included. For example, both Thomas Unthank and Fred Dabney, who had been late additions to the General Executive Committee for the Republican convention, were appointed to the committee. Other black members of the Civic Improvement Committee included Chester Franklin, Mrs. Myrtle F. Cook, Edwin S. Lewis, Dr. William J. Tompkins, and T.B. Watkins. As Kansas City entered its next phase of growth, the city continued to measure itself against regional rivals and grapple with racial division.

Kansas City’s Ten-Year Plan identified new priorities and reintroduced municipal projects that had failed to gain voter approval in 1928. The Convention Committee, for example, argued for new facilities. Members noted that Kansas City had failed to land numerous national conventions due to inadequate meeting space. Further, members noted that Cleveland, which had hosted the 1924 Republican convention, had recently finished a new municipal auditorium in 1922, and St. Louis was also planning a new facility.

Between 1928 and 1938, Kansas City’s Ten-Year Plan set the city abuzz with construction. The initiative included infrastructure projects, such as an updated sewer system and water works facility, as well as improvements to numerous roads and parks. The plan also envisioned multiple building projects, such as a new courthouse, police headquarters, and municipal auditorium. In 1938, Chamber of Commerce members commissioned Where the Rocky Bluffs Meet: The Story of the Kansas City Ten Year Plan. The retrospective reported on the success of many municipal improvement projects and argued that the Ten-Year Plan helped Kansas City survive the Great Depression because it allowed the city as “to obtain its full quota of federal work-relief millions, and to use those funds not in haphazard jobs of expedience, but in an orderly program of needed public improvement.”

By most measures the Republican National Convention proved a resounding success. The political gathering in the summer of 1928 brought concentrated attention to Kansas City. Reporters and newspaper columnists filed numerous reports on political developments and their impressions of the Kansas City community. Visitors from across the nation, many seeing Kansas City for the first time, packed the city’s hotels, toured the city’s roads, and enjoyed the city’s amenities. Carefully choreographed pamphlets and newspaper publicity touted the achievements of Kansas City’s residents and businesses. Organizers’ careful planning and the collective enthusiasm of countless volunteers ensured delegates and attendees were treated to a firsthand view of Kansas City. They enjoyed the landscape created by the City Beautiful Movement and the updated infrastructure built during the Get-it-Done campaign.

In the eyes of many, however, a great deal of work still needed to be done. The projects rejected by voters in the spring of 1928 remained unfinished. The decision to segregate delegates during the convention revealed ongoing racial tension within the city. Consequently, the 1928 Republican National Convention represented a pivotal turning point for Kansas City. The event revealed persistent divisions that threatened to disrupt municipal growth and undermine the carefully choreographed vision of Kansas City’s transformation. Yet, it also bolstered civic pride and reinvigorated interest in developing a plan for Kansas City’s future. Preparations for the convention helped to unify Kansas City’s business community and provided numerous city leaders, most notably Conrad Mann, valuable organizing experience. Adoption of the comprehensive Ten-Year Plan, which included many previously proposed projects, following the summer gathering ensured that the Republican National Convention would continue to influence Kansas City during the following decade.

A longer version of this article is published in the book, Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era (University Press of Kansas, 2018), edited by Diane Mutti Burke, Jason Roe, and John Herron.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.