"The Event of the Season": Charity, Politics, Dancing, and Jazz near 18th and Vine in the 1920s

Society is demanding higher standards in all of its social phases. Bennie Moten and his Musical Cohorts have raised the standard of Dance Pleasure and announce the lease of the Big Hall at Fifteenth and Paseo for the indulgence of Colored Devotees of Terpischorean Delight. With the best possible dance floor, the best installed acoustics for carrying the best Music, a good time is assured at all times.

This quote appeared in Kansas City's leading African American newspaper, The Call, in March 1924. It announced the leasing of the Paseo Dance Hall, located at 15th and the Paseo and one of the biggest and most elaborately decorated dance halls of the Midwest. The lessee was the African American bandleader Bennie Moten, who established the venue specifically for the patronization of Kanas City’s black community. At a time when the city was deeply segregated along racial lines, the city’s jazz bands were a source of great pride for the black community, providing music for dancing, socializing, and fundraising events.

When people think of Kansas City jazz in the 1920s and ‘30s, certain images come to mind: political corruption, gangster activity, and music that catered to and benefited from this type of environment. But vice and corruption were not the only elements that made the city a center of innovative music. The black middle and upper classes also supported the music and the musicians, especially at dance halls such as the Paseo Hall. And there were black organizations such as the NAACP, men’s groups like the Elks Lodge, and ladies’ groups like the 12 Charity Girls, who organized formal dances to raise funds for various institutions in the community.

During the 1920s, Kansas City’s African American population grew in numbers and living space, a result of the “Great Migration” from the South during that period. According to census figures, the black population of the city rose from 23,704 to 43,005 in 1930. Presumably, most the new arrivals were unskilled laborers. The new arrivals to Kansas City encountered an already thriving community, with a middle class of merchants and an upper class shaped by prominent businessmen and their spouses.

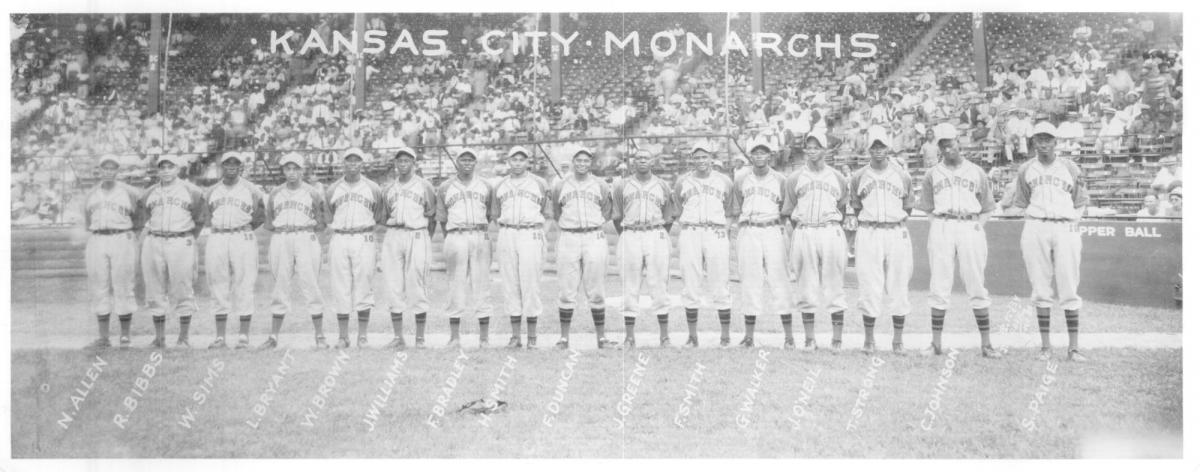

On one end of the community’s economic spectrum were those designated by Kansas City native and future NAACP leader Roy Wilkins as “well educated, intelligent, hardworking successful people whose standard of living matched anything in the surrounding white community…and whose ethics were higher than those of the local white community.” Presumably they came from families living in the city for a generation or more. Some of the most prominent African American businesses located here were Homer Roberts's car dealership, the T.B. Watkins funeral home, the offices of The Call, and the Monarchs baseball team. By the early 1920s, this group had established a thriving black commercial district in the 18th and Vine neighborhood, and the number of businesses increased substantially throughout the late 1930s.

On the other end of the spectrum were laborers such as Fred Hicks, a hod carrier (someone who carries bricks and supplies to skilled brick layers), whom this author interviewed in 1996. Although a member of the working class, Mr. Hicks was also an active union member, and a frequent patron of the dances and events described in this essay.

Community leaders such as Chester Arthur Franklin, the editor of The Call, urged the long-time inhabitants to support the new arrivals. In September 1923, he wrote in his newspaper, "Take a walk around your block and get acquainted with your neighbors. There are some mighty fine people whom you do not know. Suppose you had gone a thousand miles to see a new home, where your children could be educated and your wife could be safe, and then you found no welcome, would you like it? Would you give of your best to the new community? Would you be able to do your best for yourself?" Such accommodation must have led to the expansion of men’s and women’s social groups, as well as to the subsequent expansion of dancing to jazz in the community.

As the black community grew during the 1920s, social and political organizations were forged with the stated goals of bettering black life and improving the prospects of the race in the entire country. There were organizations with national ties, such as local chapters of the Urban League and the NAACP; fraternal lodges catering to the male economic elite, including the Pythian Knights and the Elks Lodge; ladies’ auxiliaries, catering to the female economic elite, such as the Forget-Me-Not Girls; and clubs for young men, including the Cheerio Boys and the Beau Brummels.

Each of these organizations held dances and staged other musical events that employed jazz-influenced dance bands. Many bands and individual musicians drew significant income from these events, and the venues offered a completely different performance atmosphere than the after-hours establishments that were more commonly associated with vice and political corruption.

The first mention of the word "jazz" in the Kansas City black press is found in another prominent black newspaper, the Kansas City Sun, in 1917. There was an announcement in September of that year for a dance to be held at the M. & O. Hall, which had been newly painted and wallpapered. The dance was for members of the Cosmos Club, who were implored to "make this the grandest affair in the history of this, the most famous dancing club of Greater Kansas City." And to make sure that proper decorum was kept, the article stated that dance instructor/moderator Prof. Frank Buckner "will lend the magic of his presence on the floor."

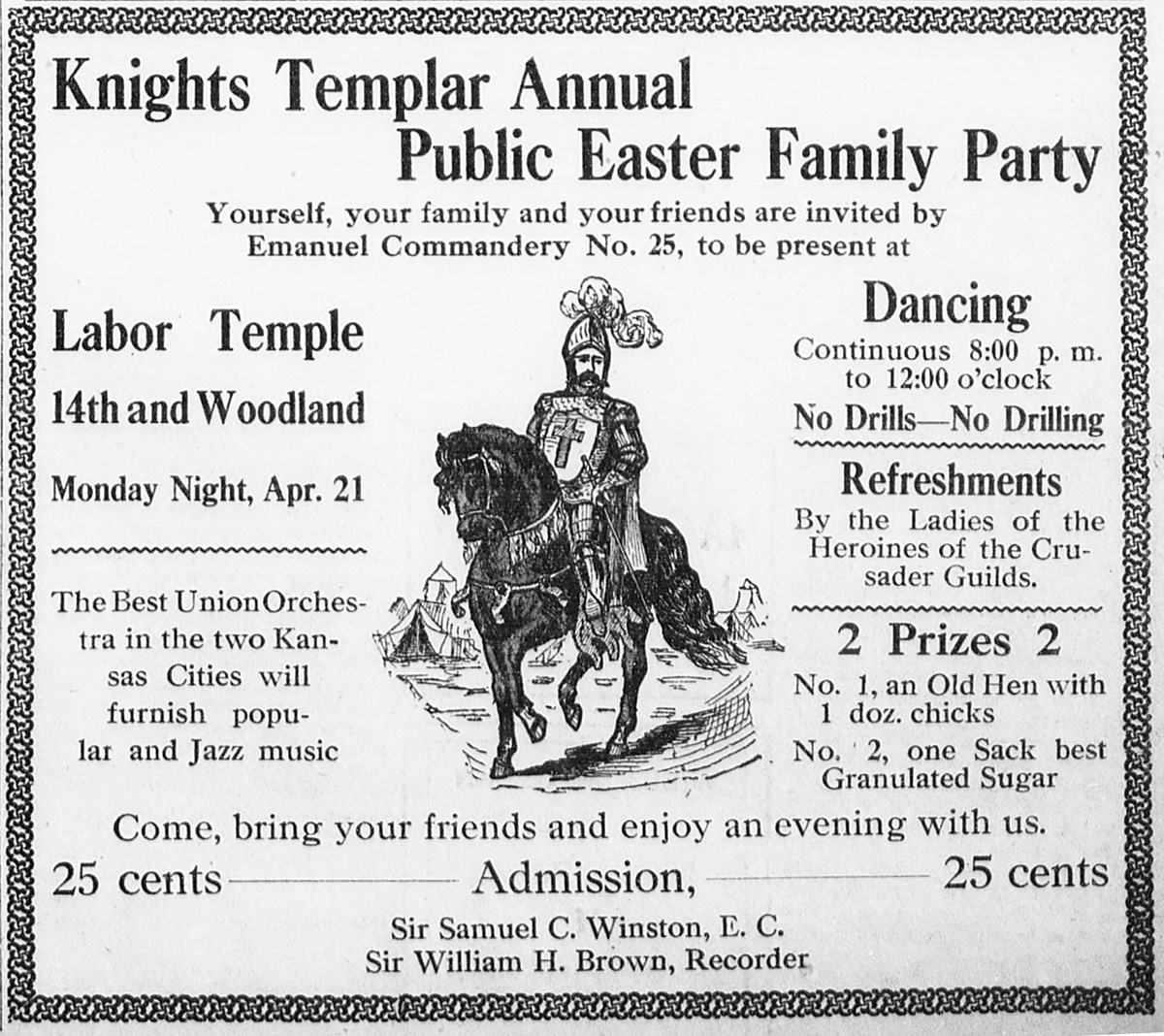

By 1919 the fraternal lodges and benevolent groups were beginning to employ bands that played jazz-oriented dance music for fundraisers and recruiting events. This Knights Templar advertisement, from April 1919, shows the elaboration typical of the largest events. Easter, a time for nice weather and new clothing fashions, continued to be an important time for charity dances.

Also by 1920, a trio led by pianist Bennie Moten began to play dances at the Labor Temple, a building at 14th and Woodlawn that served as a meeting place for many of the city's labor unions, both black and white. As a member of the Hod-Carriers union, and frequently in attendance at the Temple's dances, Kansas City native Fred Hicks was quite familiar with the building. He recalled that the first floor was divided into rooms for union meetings, and that

The dance hall was kind of upstairs . . . . It wasn't too large but it was large enough to give a dance . . . all night dances. You'd like to go there about 12 o'clock, dance till about 5 in the morning. That's where the people went. That was a dancing hall [audible emphasis].

By 1922 groups led by Bennie Moten were a regular feature at the Labor Temple. These dances were Moten's first performances for the elite class, who expected a different type of music than that of the brothel or gambling den. Such an event was advertised in The Call in the spring of 1922: "All the latest dances [will be] introduced and featured. Special entertainment for those who do not dance. Profs. Buckner and Beach, floor managers." Later in the year, in September, The Call announced the formation of a dancing club and introduced a caveat aimed at an exclusive membership: “Opening Dance at the Labor Temple under the auspices of the New Way Dancing Club. Plenty of Soda Pop and good old punch. Note: We wish the patronage of respectable people only.”

In February 1922, the African American order of the Knights of Pythias gave "A Grand Ball," featuring the "B. B. and B. Orchestra," with a 35-cent admission charge. The orchestra also performed for the Black Elks annual "Priest of Pallas" Charity Ball at the Labor Temple, in both 1922 and 1923, by which time the group had received the title of the "Elks Official Orchestra." And in October there was a "Halloween Dance" benefit for the Niles Orphan’s Home, held at Shriner's Hall in Kansas City, Kansas.

In the autumn of 1923, the Moten Orchestra made their first recordings for Okeh. The event was announced in The Call on the front page, with a photo of the band and an article detailing the titles of the recordings. At this point they were a six-piece ensemble, and the photo shows the band with record store owner/promoter Winston Holmes seated at center, with the two singers who were added for this first session - Mary Bradford on the left and Ada Brown on the right.

Winston Holmes rehearsed and prepared the Moten Orchestra for their Okeh recording dates. Holmes had a shop at the corner of 18th and Highland, where he sold "race records," phonographs, and radios. He also had recording equipment, and in 1925 formed his own recording company, the Merritt Recording Company, which specialized in blues singers and sermons by African American preachers.

The 1923 recording sessions produced eight sides, which show the influence of the two most popular styles of black vernacular music of the early '20s. Two tunes, "Elephant's Wobble" and "Crawdad Blues," were instrumentals in a 2/4, "Dixieland" feel, akin to the collective improvisation of the New Orleans bands. The other six recordings were vocals for female blues singers. For their 1923 recording sessions, Winston Holmes and the Moten Orchestra tapped into the popularity of the New Orleans musicians who had recently migrated to other parts of the country, especially Chicago, and of the black female blues singers whose sudden popularity among African American record buyers was then changing the recording industry.

Before 1922 the industry paid little attention to black artists, but in that year, the surprising sales of Mamie Smith’s "Crazy Blues" revealed to producers and executives that the new migrants to the urban North now had buying power. Indeed, throughout the early 1920s, advertisements for recordings by Mamie Smith, Bessie Smith, and other blues singers can be found in The Call. Witnessing this, Winston Holmes connected the Moten Orchestra with singers Ada Brown and Mary Bradford, and made the arrangements with Okeh for the first sessions.

"Elephant's Wobble" is not exactly an exhibition of virtuosity, but it does reveal the youthful exuberance of the musicians and their audience. It is an instrumental, a series of 12-bar blues choruses beginning with collective improvisation in the New Orleans "Dixieland" fashion, followed by solo choruses for trombone, cornet, clarinet, and banjo. The outstanding soloist is the teenage cornetist Lammar Wright, whose rhythmic attack and melodic sense clearly emulate King Oliver. Another featured soloist is clarinetist Woodie Walder and his unique method of blowing his mouthpiece into a glass to create "novelty" squeaks, like those of Larry Shields in the Original Dixieland Jass [sic] Band, which had been recording since 1917.

These early recordings made the Moten Orchestra even more popular in Kansas City. And they continued to perform for the black middle and upper class. They were featured at one of the most elaborate charity events of the time, held the week of December 6, 1926, at the Lincoln Hall on 18th and Vine. Sponsored by the black Masonic Lodge, this affair featured different types of entertainment each night. Monday was "Masonic and Suburban Night," Tuesday was a "Masked Mardi Gras," Wednesday was "Civic Night," Thursday was "All Fraternal Night," and on Friday prizes were awarded, including a "ton of free coal." The event featured most of the popular bands in the city, including those of George E. Lee and Maceo Birch, and Cooper's Military Band, in addition to the Moten Orchestra.

In 1924 Bennie Moten began to lease the previously whites-only Paseo Dance Hall, located at 15th and Paseo, and opened it up to black audiences. According to Fred Hicks, who attended many dances there, the Paseo Hall catered to the “elites,” and one had to dress appropriately. There was a big crystal chandelier, and in contrast to stereotypes of dance halls, absolutely no vice, including alcohol consumption, was tolerated.

The men’s lodges continued to sponsor dances at the Paseo Hall, and many were quite elaborate. The Elks were particularly active in using dance events to raise money and awareness, and they sponsored dozens of dances during the decade. Held in 1928, the Elks hired Chauncey Downs and his Rinky Dinks, as the Moten Orchestra was on tour. It is in support of a contingent that they were about to send to a convention in Chicago. In addition to the Kansas City Elks, other lodges from towns in the region were also in attendance and brought their own marching bands. The marching parade, taking place before the dance, was done in a darkened Paseo Hall, with flashlights.

In addition to the men's lodges, there were other types of African American social clubs formed by members of the upper class. Some of the most prominent clubs held regular dances, especially for fundraising, which employed the Moten Orchestra or other jazz ensembles. These clubs and their activities were prominently featured in the pages of The Call throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In particular, the announcements for benefit dances sponsored by the men's San Souci Club, the Beau Brummels, and the Cheerio Boys; and the women's Forget-Me-Not Girls, and the Nit Wit Club indicate that they were an important component of the entertainment life in black Kansas City during the 1920s.

The dances sponsored by these clubs were often charity benefits, and in the case of the Beau Brummels and the San Souci Club, these were annual events. They could also have elaborate themes and extra-musical entertainment. In 1920 a "Vaudeville Review, Carnival (and) Dance," was given in 1925 by the Beau Brummels and featured the Moten Orchestra to benefit the Niles Orphan Home. In 1928 a show held at the Paseo Hall combined dancing to the music of Chauncey Downs with a circus theme, for the benefit of the Florence Home for Girls and the Kansas City, Kansas Orphan’s Home.

In addition to having luncheons, teas, and card games, black women’s groups also sponsored charity dances, which employed the city’s black dance orchestras. There were several dozen such groups which were organized by the City Federation of Colored Women's Clubs. Some of the wives of jazz musicians were involved in these clubs, including the wife of the Moten trombonist Thamon Hayes, a member of the "Forget-Me-Not Girls."

The women's auxiliaries raised money for several charitable causes that benefited the black community, one of the most important of which was Wheatley-Provident Hospital at 18th and Forest. The segregated black hospitals in Kansas City were not only a provider of health care; they also played an important role in shaping the community's identity. In addition to providing medical care to black patients, Wheatley-Provident and its public counterpart, General Hospital No. 2, employed black doctors and nurses, offered intern training programs, and provided opportunities for black middle class professionals to assert political leadership roles. The fundraising events for the hospital were often elaborate dances or other events that employed the community’s jazz orchestras.

Each spring, beginning in 1918, a Fashion Show was organized by a women’s group in support of Wheatley-Provident. In 1920 it was held at the Labor Temple, with dancing featured after the show. It raised $606, and the organizing auxiliary “wished to thank every citizen of Kansas City for helping to make this a record-breaker. Each lady of the Auxiliary put forth every effort to make the Fashion Show a success, and they feel proud of their effort.” President of the Auxiliary was Effie Watkins, wife and sister-in-law of John T. and T.B. Watkins, Kansas City’s most successful black funeral directors.

The Fashion Shows continued into the 1930s and became more elaborate each year. An advertisement for the 1928 show promised parades, men’s fashions, and revues followed by dancing to the Rinky Dinks. By 1930 the show drew "slightly more than 5,000 persons." Its theme was 'Fashions in a Garden,' and it included a fashion show, a circus, and a concluding dance with music by the Moten Orchestra.

There were 137 models in the fashion show, 24 ballet, 10 soft shoe, and 25 toe dancers at the dance, plus a snake charmer, tight rope walker, and bearded lady for the circus. It was held at Convention Hall, and admission was 50 cents. Two months later, the "Council of Men's Clubs" sponsored another dance benefit for Wheatley, with four orchestras, including Bennie Moten's, providing the music.

The Fashion Show was just one of many benefit dances that were sponsored each fall and spring. For example, in March 1925, the Moten Orchestra played a benefit for the Douglass Hospital and Orphan Children's Home of Kansas City, Kansas, sponsored by the Parliamentary and Culture Clubs. They played a "Barn Dance" sponsored by the "Harmony Literary Art Club" at the Labor Temple in April. Later that month the orchestra performed at an important event, a "Charleston Wedding," given by the "Twelve Charity Girls."

The sorority Delta Sigma Theta, consisting of students at Lincoln University, also held charity events that featured jazz. Lincoln, Missouri’s historically black college located in Jefferson City was a source of pride for the African American community. The Call regularly featured stories on the matriculation of local students and printed editorials that saw the University as a contributor to racial uplift. For example, an editorial once stated, “[The Board of Curators of Lincoln] has caught the spirit of constructive change, and hold fast to what is good, they have wrought a wonderful improvement. With rare good judgment they have inspired the faculty so it is harnessed up to the bigger vision . . . .”

A dance organized in April 1926 was characteristic of Delta Sigma Theta’s charity events. They held a “college cabaret” at the Labor Temple, featuring dancing to the Bennie Moten Orchestra. Advertised as “Restful, jolly, artistic, and beautiful,” the sorority announced that “Bennie Moten’s orchestra will tempt you to trip it lightly on your toes if you enjoy that form of recreation, or should you prefer to sit quietly enjoying the refreshments and graceful performances offered in the special features.” There were elaborate table decorations and waitresses “eager to make your evening the best ever.” Proceeds went to Wheatley-Provident Hospital.

By the early 1920s, the NAACP had become an important part of political expression in Kansas City’s black community, and their meetings and rallies featured music by the local bands. As the group’s leaders announced in The Call:

Except one hold himself cheaply, he will join the NAACP. It is less for the dollar membership fee, than for the force that each person gives the cause, that all should join in the coming membership drive . . . it is because the NAACP has the desire to better the condition of the Negro in America, and because it has won some considerable successes, that the membership of us all in it is vital.

The city's NAACP also sponsored musical events that raised money for the organization's national fund. One such affair, which occurred in 1931, was a "Cabaret Minstrel," a kind of variety show in which "one hundred or more people . . . entertained with pop songs and light classics." Some apparently wore minstrel cork and performed skits. These were not professional entertainers, and none were jazz musicians; rather, they were citizens affiliated with the organization who for the most part came from the middle and upper class of society.

As jazz and dancing became more popular in the late 1920s, the local branch of the NAACP hired the city’s jazz bands to play benefit dances. An advertisement for one such event, held at the Paseo Hall in 1927, announces a "Greenwich Village Dance," in solidarity with the authors and musicians of the Harlem Renaissance. There was also a costume element to the dance:

Fifty cents only, a reasonable fee,

Good 'cause you will be helping the NAACP.

Everybody come, whate'er your size,

The best costume there brings a grand prize.

The Kansas City chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the black-nationalist group formed by Marcus Garvey, also hired the Moten Orchestra. Garvey believed in racial unity, pride, and complete autonomy, and his activities, including marches and demonstrations, are well-chronicled in The Call during the 1920s. One of the most prominent supporters of the Garvey movement in Kansas City was the Moten Orchestra’s early promoter Winston Holmes.

The Kansas City division of the UNIA met at Lincoln Hall included speaker W.A. Wallace, who was a former businessman and current state commissioner in Illinois. Oscar De Priest, also present and also from Illinois, was waging a successful campaign to become the first African American to be elected to Congress in the 20th century. Two hours of speeches on behalf of the UNIA concluded with dancing to the Rinky Dinks.

The Moten Orchestra’s final recording session was in December 1932. By this time the band had been established as Kansas City’s premier black ensemble for several years. It had grown from six pieces to 14, including the important additions of Walter Page, whose upright bass-playing transformed the rhythm section; Eddie Durham, a trombonist whose arrangements led to an expansion from three to four-part harmony; and pianist Count Basie, who also served as an innovative arranger for the band. In addition, several trips to the east coast in the late 1920s had introduced the band to the new Lindy Hop rhythms, which they subsequently adopted and brought back to Kansas City.

The band's late style is revealed in the 1932 tune "Toby." Like several other sides from this recording session, it is very fast, influenced by the Lindy Hop, and the swinging abilities of Walter Page. The plodding 2/4 rhythm of “Dixieland” has been replaced by the lighter 4/4 feel of the newer dances. Unlike the 12-bar blues sides of the 1923 sessions, “Toby” and most of the other tunes on this session follow the 32 bar AABA popular song structure. The arrangement is much more sophisticated than anything on the 1923 sessions. “Toby” opens with a chorus for harmonized reeds, with a guitar solo by Durham on the bridge. Then follow solo choruses for trumpet and tenor sax, which are accompanied by harmonized reeds. The last choruses are interchanges of brief melodic ideas or “riffs” between harmonized brass and reeds, with solos for alto sax and trumpet on the bridge, which foreshadows the signature “riffing” technique of the later Count Basie Orchestra.

Undoubtedly, dance music was an integral part of life in black Kansas City during the 1920s, however, in the 1930s these dances declined in popularity. The Great Depression led to a sharp decrease in fund-raising events. The Depression greatly impacted the African American community, with the loss of jobs, businesses, and discretionary incomes available for entertainment or fundraising.

The formally organized dances were also affected by changing musical tastes and by the growing power of politicians and underworld figures over nightlife in the black neighborhoods. Beginning in the early 1930s in Kansas City, there was a transition in dance halls from the semi-formal ballroom style venues toward nightclubs, which offered floor shows in addition to dancing. During the late 1920s, nightclubs, often sponsored by underworld figures, had become very popular among white audiences. The Cotton Club in Harlem and the Pekin Cafe in Chicago were two of the most famous examples. In Kansas City in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the white El Torreon, the black Cherry Blossom, and eventually the segregated Reno Club were established in imitation of nightclubs in other cities. Eventually, even the patrician Paseo Hall was transformed into such a venue.

The popular notion of Kansas City jazz is that of the nightclub, the politician, and the gangster, not the charity event. Yet, for much of the 1920s, Kansas City’s middle and upper classes were the primary economic supporters of the community’s jazz musicians. Their dances provided the bandleaders with steady work and allowed the individual musicians to develop their technique to forge into cohesive ensembles. The full story of Kansas City jazz cannot be told without acknowledging this contribution.

A longer version of this article is published in the book, Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era (University Press of Kansas, 2018), edited by Diane Mutti Burke, Jason Roe, and John Herron.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.