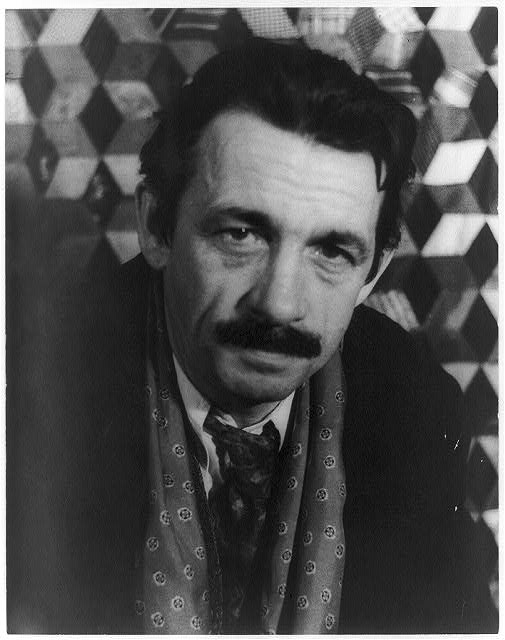

Thomas Hart Benton

- Date of Birth: April 15, 1889

- Place of Birth: Neosho, Missouri

- Claim to Fame: painter, muralist, and leader of Regionalist movement in American art

- Spouse: Rita Piacenza Benton

- Also Known As: “Tom” Benton

- Date of Death: January 19, 1975

- Cause of Death: heart attack in his Kansas City studio

- Final Resting Place: Cremated; ashes scattered at Martha’s Vineyard

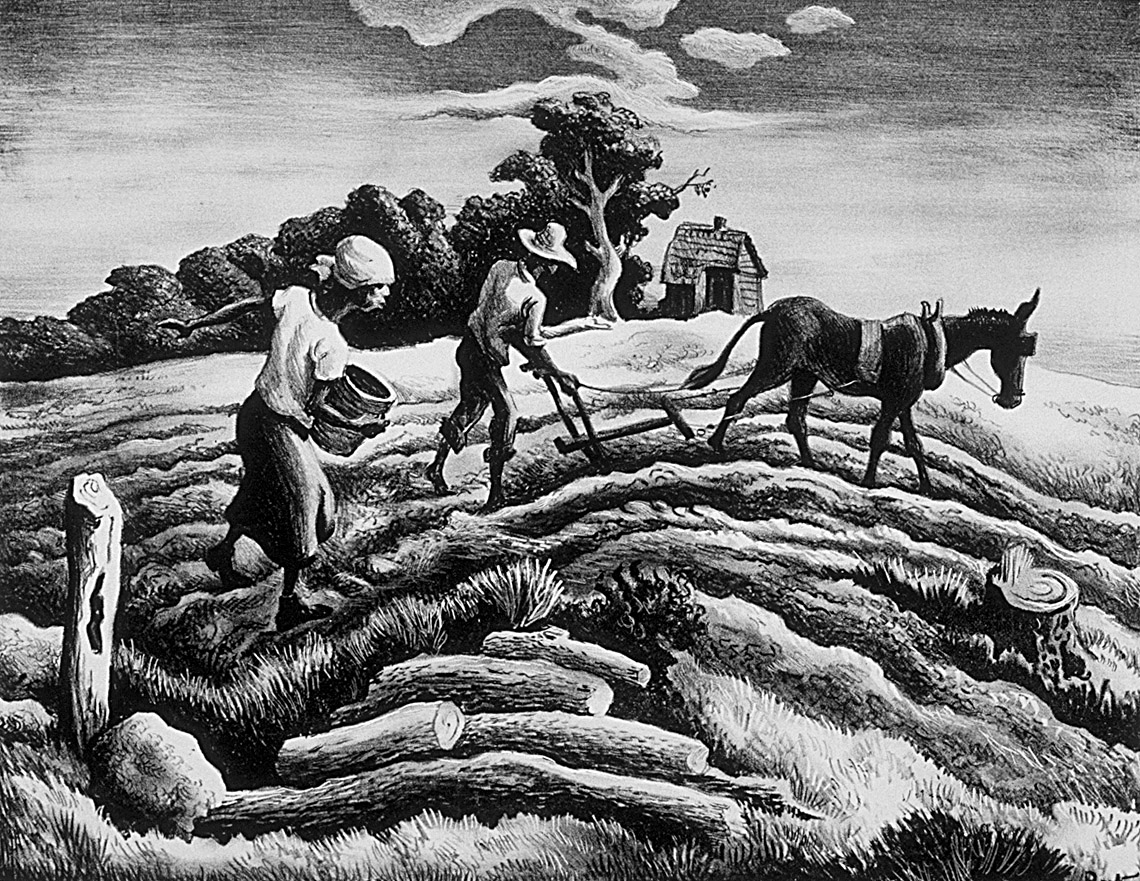

Thomas Hart Benton, one of the leaders of the Regionalist movement in American art, was a prolific painter, muralist, draughtsman, and sculptor from childhood until the end of his life in 1975. Today he is best known for his realist depictions of American life, which, in his own time, were perceived as directly opposed to modernist movements cultivated in Europe. His paintings, largely vignettes of daily life and ordinary rural characters, were simultaneously praised for their frankness and criticized for their gritty representations of American culture and history.

“Tom” Benton was born in 1889 in Neosho, Missouri, to a prominent family in state and national politics. His noteworthy relatives include Samuel Benton (Confederate Civil War general), Thomas H. Benton Jr. (Union Civil War Brigadier general), and Henry Clay (senator, cabinet secretary, and three-time presidential candidate). Benton’s father, Maecenas Eason (“M.E.”) Benton, U.S. Congressman, hoped Benton would study law and pursue government office, while the artist’s mother, Elizabeth Wise Benton, supported her son’s artistic interests from childhood.

The eight years (from 1896-1904) that M.E. Benton served as U.S. Congressman in Washington, D.C., split his family’s time between the capital and their small Missouri hometown. Both environments would inform Tom Benton’s later artistic interests. Washington afforded his earliest encounters with art; at a young age, he was exposed to the neoclassical architecture and narrative murals decorating the U.S. capitol building. An avid drawer, he absorbed the Washington Post cartoons of Clifford Berryman, emulating his style. Benton’s Missouri roots were especially formative in his realist scenes of daily life. He perceived the rural communities of the South and Midwest as less contrived and affected than the people he encountered in New York and in Europe, and thus more representative of average Americans.

Following his family’s return to Missouri from Washington, Benton began working at the Joplin American newspaper. Looking to Tom’s future, father and son reached a compromise. In 1907, Tom would attend the Western Military Academy in Illinois, and upon graduation his father would allow him to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. Before the academic year concluded, though, Benton transferred from the military school to the Art Institute. He attended the Académie Julian in Paris the following year.

By 1912, Benton was financially independent, though struggling, and working as a portraitist in New York. As the United States entered World War I, he joined the Navy. During this time at a Norfolk Navy base, Benton focused on representational paintings and drawings (as opposed to the various modes of abstraction that he explored in Paris). Recording the base’s machinery, buildings, and ships proved critical to his career. After years of limited success emulating European modernism, he embraced his long-held love of drawing. Emphasizing composition and underlying design over paint-handling would become Benton’s distinctive aesthetic.

Benton’s junctures in Chicago and Paris exposed him to media he had not previously tried, especially painting, and encouraged experimentation in style and subject matter. In Benton’s words, returning to drawing “was the most important thing that, so far, I had ever done for myself as [an] artist. My interest became, in a flash, of an objective nature.” He explained that drawing the structures, machinery, and ships there “tore me away from all my groomed habits, from my play with colored cubes and classic attenuations, from my aesthetic drivelings and morbid self-concerns.” While in Norfolk, Benton conceived of The American Historical Epic (1919-1924), which epitomizes his emphasis on three-dimensionality, distinctly American subject matter, and fundamental compositional structure.

Benton married Italian immigrant Rita Piacenza (1896-1975) in 1922, and they had one son, Thomas Piacenza (“T.P.”) Benton (1926-2009) and one daughter, Jessie Benton (1939- ). In the early years of their marriage in New York, plus summers at Martha’s Vineyard, Tom and Rita lived in poverty. Tom had been in the habit of destroying most of the works he completed, but Rita carefully saved his paintings and showed them to dealers around the city.

Throughout the 1920s, Benton embarked on annual solo trips for weeks or months at a time, touring the rural South and Midwest. By the late ‘20s, Benton’s interest in representing scenes of everyday American life with the visual language of realism gave way to a style that brought him financial success, critical attention, and high profile commissions. This would be branded as Regionalism in the 1930s. In 1934, a Time feature, “The U.S. Scene,” popularized the group and presented Benton as the movement’s leader. Described as the Midwestern mode of painting, Regionalism aligned Benton with artists John Steuart Curry (from Kansas) and Grant Wood (from Iowa). By 1930, he had embraced his Missourian identity and completed four large-scale mural commissions that brought him national renown.

In September 1935, Benton received two offers which compelled him to leave New York for Kansas City: an invitation from the Kansas City Art Institute to head their painting department and a mural commission for the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City. The finished capitol mural, A Social History of the State of Missouri (1936), elicited polarized responses in the state legislature. While some viewed the design as too chaotic, others believed it was accessible to understand and engaging. Some viewers argued that the mural was too critical of the state and others expressed that it was not critical enough. Finally, like most of Benton’s works, some viewers praised his approach as frank and truthful while others complained that his style was in poor taste. Benton has stated that the Jefferson City commission “completed the last phase of my development as an artist” and that it was the best work of his career.

Benton’s mural for the Missouri State Capitol represents his life and career in terms of technical accomplishment, but also in terms of his background and character. Since childhood, Benton’s affinity for rural, working-class American life contrasted his upbringing in a socially and politically prominent family. Benton associated with a wide variety of personalities and backgrounds; on his extended travels throughout the rural South and Midwest, he was often hosted warmly in strangers’ homes. In Kansas City, Benton was acquainted with political boss Tom Pendergast, city planner J.C. Nichols, banker William T. Kemper, and Harry S. Truman. Pendergast, Kemper, and Nichols appear prominently in the Missouri State Capitol mural, and Benton worked closely with Truman on designs for Independence and the Opening of the West (1959-1962) at the Truman Presidential Library and Museum.

As head of painting at the Art Institute, Benton had a large following of students. He also had a long history of prejudiced statements toward homosexual people, though, and after publicly accusing several employees of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art of homosexuality, he lost his position at KCAI in 1941. Even after this dismissal and the waning of Regionalism, Benton continued to be successful, perhaps, unexpectedly, because his difficult personality and controversial oeuvre stirred mixed, but constant, critical attention.

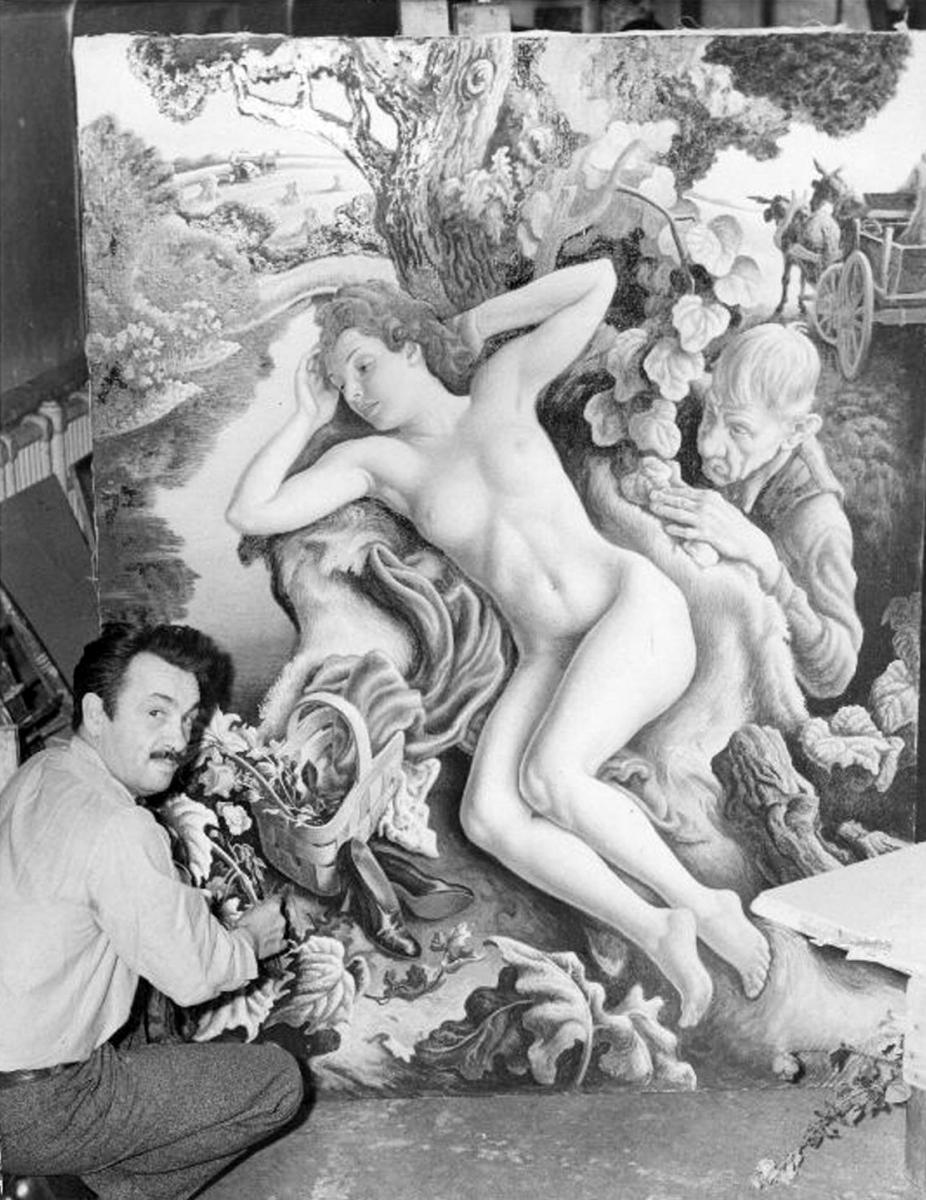

Notwithstanding Benton’s firing from the KCAI, he continued to live in Kansas City for the rest of his life. The several years after he completed his mural at the Missouri State Capitol were intensely productive. Persephone (1939), The Year of Peril series (1941-1942), and Benton’s first autobiography, An Artist in America, were created during this period, and they are among the best known works of his entire career. Despite frustrated and disenchanted comments about Kansas City—that it did not have the potential to be an artistic center rivaling New York as he hoped—Benton’s career saw its greatest success and productivity in Kansas City. He stayed there until his death in 1975 and lived at 3616 Belleview Avenue for nearly 40 years.

Audiences often question Benton’s views toward African Americans, given his caricatured depictions of people of color and his propensity for harsh commentary about people and institutions regardless of their racial background. While his paintings are open to viewers’ interpretations, Benton’s support of the NAACP and American Civil Liberties Union are worth noting; for example, he contributed work to a 1935 exhibition organized by the NAACP, “An Art Commentary on Lynching,” and Roger Baldwin, founder of the ACLU, was a close friend. In paintings such as A Social History of the State of Missouri, which includes imagery of lynching and a slave auction, Benton exaggerates the features of every figure. Even imagery of people whom he knew personally and held in high regard, such as The Sun Treader (Portrait of Charles Ruggles), appear caricature-like. Some viewers critiqued his representation of African Americans in poor conditions; Benton believed he was shining light on the negative aspects of Missouri history and its continuation of indentured servitude, at a time when many artists did not paint people of color at all. Artistically, Benton seems to have believed that his crude realism and candid subject matter captured American life more satisfactorily than his modernist contemporaries.

Benton’s notoriously obstinate temperament, willingness to denounce peers’ work, and vocalize his views ensured controversy. The unusual style of his work often challenged viewers to discern the tone, political position, or meaning of his paintings. While Benton couched his realism as representative of how he viewed his subjects, viewers often viewed his figures as satirical and his subject matter as too base to be represented in art. His work represented darker sides of American life (such as racial injustice or the corruption of Kansas City politics in the Pendergast years), and celebrated the rural, working-class Americans he had encountered in Missouri, Martha’s Vineyard, and his extensive travels around the United States.

Thomas Hart Benton is the author of An Artist in America (1937) and An American in Art: A Professional and Technical Autobiography (1969). For much of his life, his works received harsh criticism, spurred controversy, and were eventually considered outmoded by mid-century abstract expressionist paintings (epitomized by the work of his pupil, Jackson Pollock). Today Benton is appreciated for asserting a distinctively American aesthetic in 20th century art. He worked prolifically until 1975, when he died of a heart attack while working on a mural in his Kansas City studio.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.