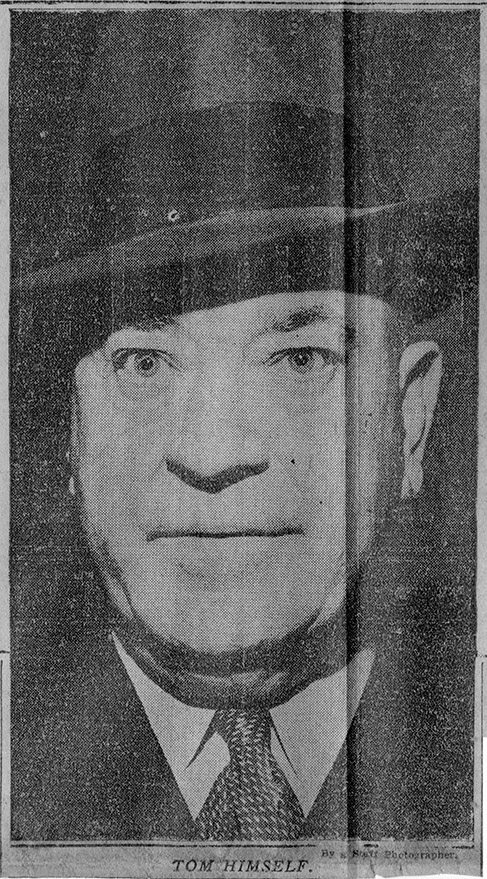

Thomas Joseph Pendergast

- Date of Birth: July 22, 1872

- Place of Birth: St. Joseph, Missouri

- Home: 5650 Ward Parkway (residence); Jefferson Hotel at Sixth and Wyandotte Streets (political headquarters until he closed the building in 1919); 1908 Main St. (political headquarters from 1927-1939)

- Claim to fame: younger brother of James F. Pendergast, political “boss” of Kansas City

- Political affiliations: Democratic Party, "goat" faction, Jackson Democratic Club

- Spouse: Carolyn Elizabeth Dunn Snider

- Also Known As: Boss Tom; T.J.

- Date of Death: January 26, 1945

- Place of Death: Menorah Hospital

- Cause of Death: heart failure

- Final Resting Place: Forest Hill Cemetery

On March 2, 1934, Kansas City’s unelected machine boss Tom Pendergast received a letter from Missouri Governor Guy Park, which read, “Sometime ago I sent you a list of the employees of the State Highway Department in the Jackson County Division and requested that you have them checked up to find who were Democrats and who Republicans. If this has been done, I would be glad to have a copy of the list and later go over it with you with a view of making such changes as might be necessary and proper.” In a prior letter on the same topic, Governor Park had enclosed a list of the employees’ payroll. What today might appear to be an astonishing violation of ethics, law, and the principle of a politically neutral civil service was in fact routine business for Tom Pendergast, the “boss” of Kansas City whose influence extended to the state government by the early 1930s.

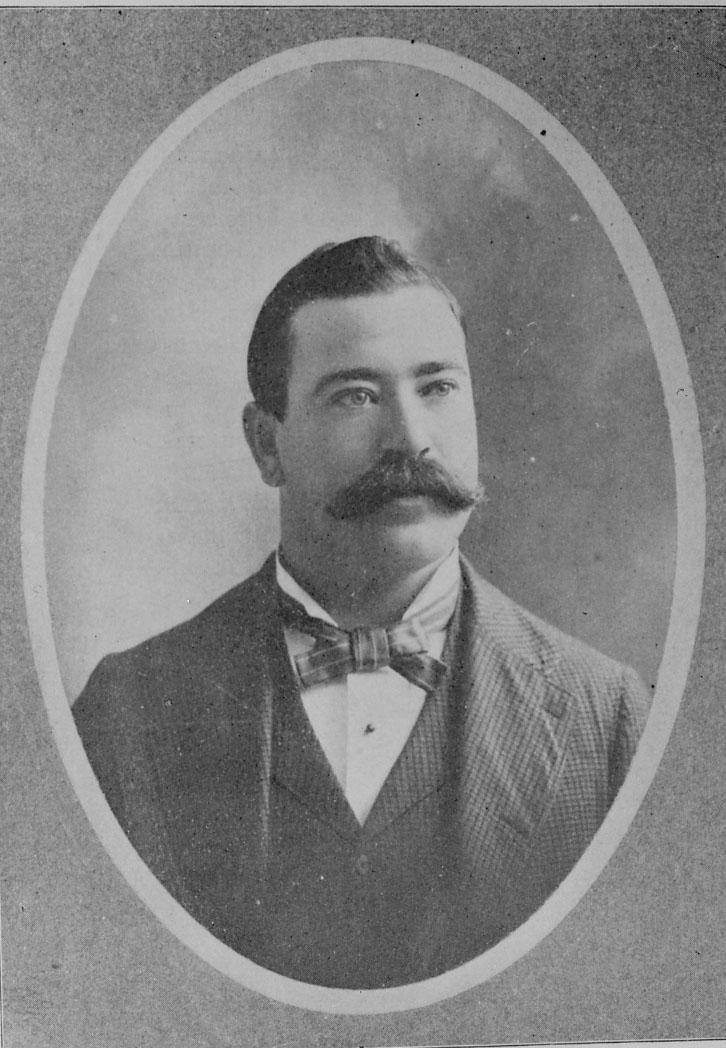

Pendergast’s unlikely political career had begun in 1894, at the age of 22, when he moved from St. Joseph to Kansas City to join his brother, James Francis Pendergast, then 38 and the oldest of nine siblings in their Irish-American family. James had already been in Kansas City for 18 years and started working menial, dangerous jobs in an iron foundry. According to local lore, James financed his first saloon, Climax, using winnings from his bet on a racehorse of the same name. No city records corroborate the existence of a Climax saloon, although horseracing would later become an integral part of the Pendergast story. It is more certain that James purchased the American House saloon at 1328 St. Louis Avenue in 1881. When Tom joined James some 13 years later, they co-owned the Pendergast Brothers Saloon at 1715 West 9th Street, in the city’s industrial West Bottoms.

Beyond mere drinking establishments, saloons in the late 19th century American West could be used to launch political careers. On the one hand, they provided a profitable trifecta of vice: liquor, prostitution, and gambling for the men who toiled long hours in hazardous factories, livestock yards, or slaughterhouses. On the other hand, saloons served an important community function for blue collar workers. Shrewd and unscrupulous business or political aspirants could advance paychecks or otherwise loan money to the downtrodden (who were ignored by reputable banks) and, in exchange, charge interest and count on their newfound clients to vote and stump in elections. Those who benefited from machine patronage and received jobs were expected to remain loyal to the party line and pay an annual “lug,” or percentage of their income. Machine bosses hired “ward heelers” who canvassed for votes through both innocuous methods (such as getting out the vote by providing chairs to elderly voters waiting in long lines) and, more famously, engaging in illegal election fraud techniques up to and including physical intimidation and violence, ballot stuffing, bribery of election officials, and misinformation campaigns against other factions’ voters. Savvy saloon owners like James and Tom Pendergast could direct their business revenues to provide food, cash payments, and coal to families in need, build coalitions of willing supporters, and gain control over government bodies to support popular municipal projects.

By 1887, James Pendergast emerged as a Democratic committeeman in the First Ward and oversaw the “mob primary,” a method of selecting a party’s candidate for alderman. As the name suggests, the process involved a public voice vote and effectively no outside oversight—the winning candidates were those who best used persuasion, bribery, trickery, or intimidation to marshal the most supporters and literally overpower the opposition to secure the party nomination. James became an alderman in 1892, even after reformers had ended the mob primaries. He solidified his power over the First Ward by using his influence to keep police pressure off the saloons and free his constituents from jail for minor crimes (especially if their crimes were related to Pendergast-owned saloons).

Of course, outside of the First Ward there were other aspiring bosses: Miles Bulger in the Second Ward (southwest of downtown), Casimir “Cas” Welch in the Sixth and Eighth (“Little Tammany,” just east of downtown), Michael Ross in the Fifth (the North End around Columbus Park, east of the River Market), and especially Joe Shannon in the Ninth Ward. Joseph B. Shannon led the “rabbit” faction of the local Democratic Party and allied with Cas Welch and several smaller bosses to control the Northside, or northeastern and eastern parts of town. As such, he was the biggest rival to Pendergast’s “goat” faction. As the goats expanded out of the First Ward, certain demographic patterns stuck; unlike the old-guard Democratic Party associated with white Southerners, the local Democratic machine constituents were diverse and more likely to be Catholic, first- or second-generation immigrants of Italian, Irish, or Mexican descent, or African American.

When Tom joined Jim as a business and political partner, he provided a sturdy physical aura and stable leadership qualities. His intimidating size and reputation as a brawler combined with an approachable and outwardly friendly, yet also blunt and resolute personality. Among other odd jobs, Tom worked a liquor and concession stand at a horseracing track named the Kansas City Driving Club. While serving as an associate to Jim—as did five of the other seven Pendergast siblings—Tom rose quickly, from First Ward deputy constable in 1894, to deputy marshal in 1896, and to superintendent of streets in 1900. The streets job foretold a lifelong pattern for Tom Pendergast, who secured 250 jobs for political allies even while establishing a citywide reputation as an effective administrator. Pendergast understood that a broad swath of constituents would tolerate corruption as long as they perceived that city services and infrastructure was being developed for the broader public benefit.

Tom Pendergast took over the political machine when James died of natural causes in 1911, although in the previous year he had already secured the alderman seat that Jim relinquished due to poor health. On February 3, 1911, he married Carolyn Elizabeth Dunn Snider (the daughter of another saloon keeper from the West Bottoms) at Our Lady of Good Counsel Church. In 1915, Tom gave up his seat on the city council and focused on his unelected role as leader of the Jackson Democratic Club, the formal party organization of the Pendergast machine that was headquartered at his Jefferson Hotel at Sixth and Wyandotte Streets. In his hotel office, he worked to ensure the election of favorable candidates to city positions.

Pendergast’s blossoming political power moved directly in line with his business interests. He or his associates owned stakes in dozens of companies that always seemed to win service contracts from a city government increasingly controlled by Pendergast’s hand-picked officials. At the machine’s peak influence, the Sanitary Service Co. contracted with the municipal government to collect the city’s refuse; Tom owned nearly half of the company’s shares. He was also vice-president of Ready-Mixed Concrete Co., which supplied concrete to the prodigious construction projects that made up Kansas City’s $50 million Ten-Year Plan—a program approved by voters in 1931 to counter the economic implosion of the Great Depression with new projects or updates including the Jackson County Courthouse, Municipal Auditorium, City Hall, Police Headquarters, streets, sewers, water works, parks facilities, signs, and sidewalks.

Other noteworthy companies with Pendergast connections included the T.J. Pendergast Wholesale Liquor Co. (renamed Pendergast Distributing Co. during Prohibition), Atlas Beverage Co., City Beverage Co. (sole distributor of Anheuser-Busch products in Kansas City), the W.A. Ross Construction Co., and dozens of others in the industries of construction, insurance, quarries, industrial machinery, coal, restaurants, and hotels. Even businesses not directly associated with Pendergast routinely had to make payments, often as much as 5 or 10 percent of gross revenue, to the machine in order to do business in Kansas City and avoid various forms of harassment or problems with licensing and city regulators. Pendergast created jobs and built huge portions of Kansas City’s infrastructure, much of which still stands today, and aside from dealing mostly in cash to obscure the flow of money, he hardly attempted to downplay the wealth he earned from public contracts.

Coinciding with the rapid expansion of Pendergast’s businesses in the 1920s and 1930s, Tom Pendergast consolidated his political power at the end of 1925 and maintained a firm grip until the late 1930s. He gained almost unchallenged control due to a change in the city government that was, ironically, first proposed by well-meaning reformers including the philanthropist William Volker. The reformers proposed a new city charter to replace the existing aldermanic system with a nine-person city council that would hire a professional city manager who would, presumably, supervise the city’s affairs in a non-partisan fashion. The mayor would hold little formal power. Somewhat surprisingly, Pendergast went along with the proposed reforms and was quoted in the Star as saying, "It ought to be as easy to get along with nine men as thirty-two [the number of aldermen in the old system]." Voters approved the new city charter. Meanwhile, Pendergast’s goats gained the upper hand over Joe Shannon’s rabbit faction with the defection of Cas Welch, boss of “Little Tammany” (just east of downtown) from rabbit to goat. A deal with Shannon gave support to Pendergast’s appointees in the general election for the city council, in exchange for the rabbits nominating a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Congress.

In a close vote, Pendergast’s candidates won a five-to-four majority on the new nine-person city council, and Pendergast dictated that the council appoint Henry F. McElroy as city manager. Other aspiring bosses, including Mike Ross and Cas Welch, fell in line. A few years later, in 1928, the Irish-American Mike Ross found himself replaced as leader of the Italian North End when several of his associates were kidnapped by one of his lieutenants, Italian-American Johnny Lazia. Pendergast initially resisted Lazia’s takeover, but acquiesced when Ross’s most important supporters switched sides to Lazia. Pendergast’s association with Lazia—the city’s leading figure of organized crime—gave Pendergast direct influence over the city’s criminal underworld, which while not formally a part of the machine, was typically tolerated as long as it gave the machine a financial cut and kept the more violent crimes out of view of respectable society. Quite conveniently for the gamblers and other criminals under Lazia’s influence, Pendergast also placed Lazia in charge of patronage hiring in the city’s police department. Although the machine claimed to crack down on hard drugs and prostitution, the bootlegging, gambling, and other “harmless” crimes continued mostly unchecked. Even unobtrusive mom-and-pop stores were known to display their illegal slot machines right up front, and McElroy famously quipped that he wouldn’t hurt small businesses by removing them.

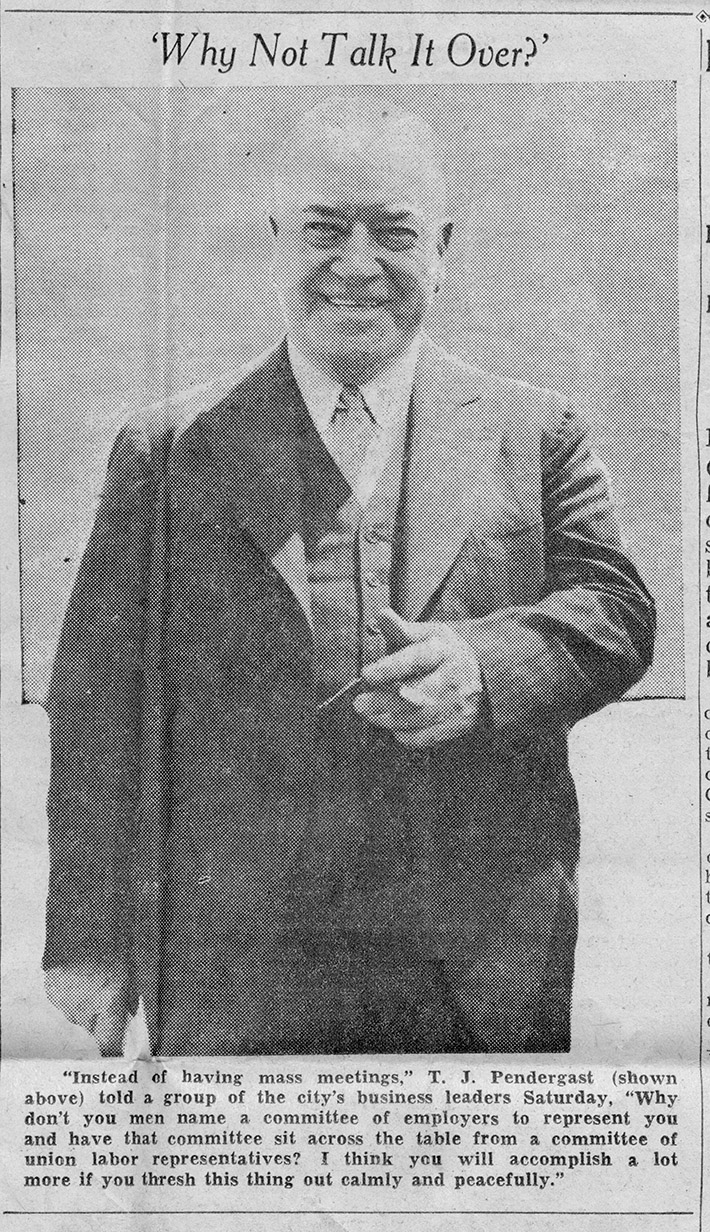

From 1925 until his indictment in 1939, Pendergast, working through proxies such as McElroy, Lazia, and other associates, dictated the terms of day-to-day business in the city, including the operations of the police department, judicial appointments, elections officials, parks and recreation, and roads. Starting in 1927, his outwardly modest office at 1908 Main Street became the de facto city headquarters, with a daily queue of politicians, businessmen, and ordinary citizens waiting in the cramped halls on a first-come, first-served basis to ask favors and make a deal with the boss of “Tom’s Town.” By these years, Tom was distancing his public image from his West Bottoms background. His classier image included a new home on Ward Parkway, unfailing attendance at mass at Visitation Church, abstinence from alcohol and drugs, evenings reserved for his family, and an early bedtime.

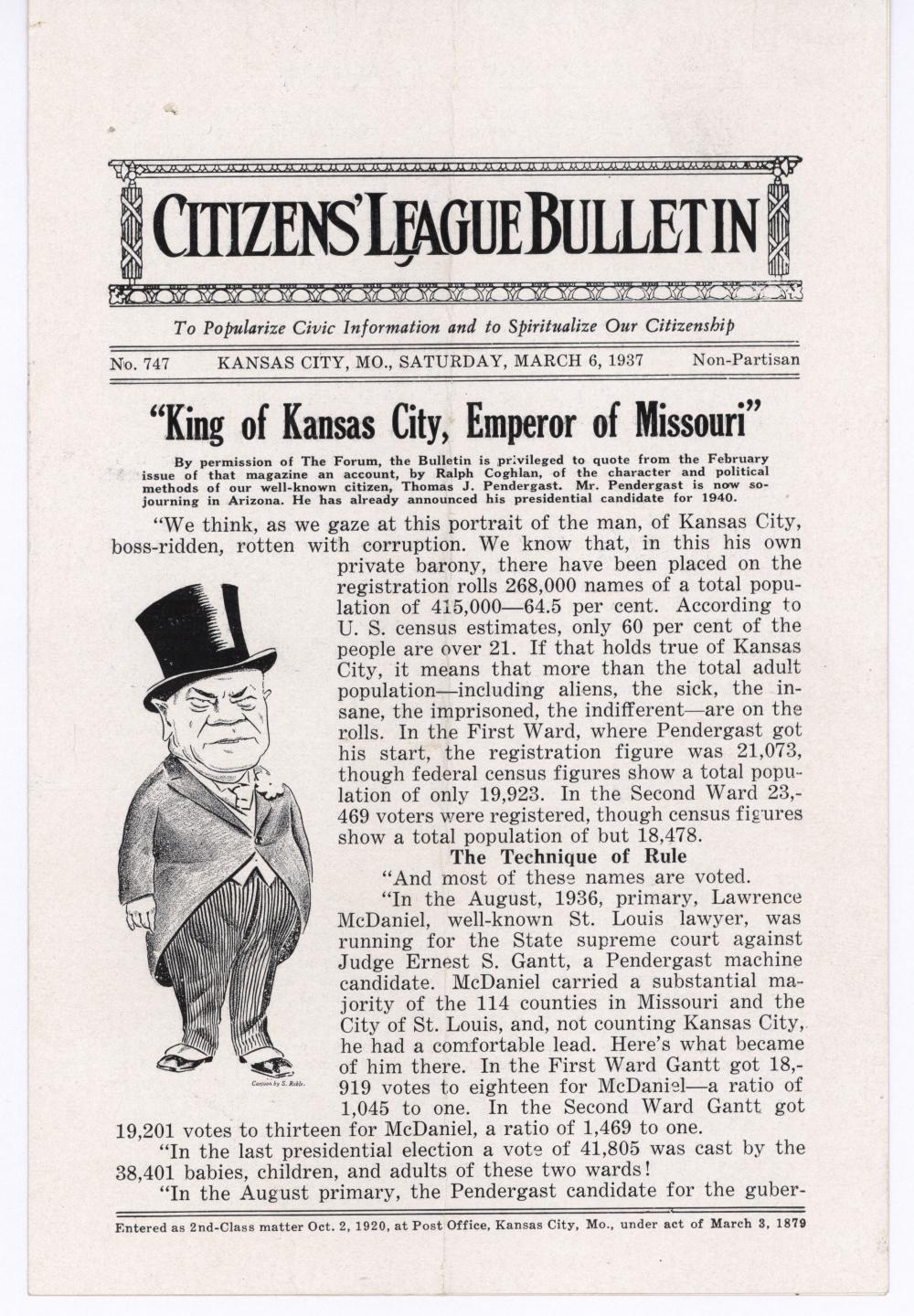

Pendergast’s influence extended well beyond the city limits to the state level and beyond. U.S. Senators James A. Reed and Harry S. Truman were closely associated with the machine, and critics of the machine accused Governor Guy Park, elected in 1932, of being such a devoted Pendergast crony that the governor’s mansion gained the moniker, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Pendergast sometimes forwarded handwritten notes, such as this May 1933 letter and this January 1934 letter, to Governor Park, with instructions about candidates for government jobs. The Pendergast faction was well represented in the Missouri delegation to the 1932 Democratic National Convention that selected Franklin Roosevelt as the Democratic nominee for president. And as president, Roosevelt hesitated to upend the status quo of Missouri’s Democratic Party structure or use federal resources to investigate machine activities, particularly reports of rampant election fraud. Federal and public scrutiny of Kansas City, however, began to grow after the November 1934 election, when thousands of fraudulent ballots were cast, four people murdered at polling stations, and an additional 11 voters shot and wounded.

Available funding for such projects expanded rapidly in 1935, when Pendergast persuaded newly elected Senator Harry S. Truman to lobby for the appointment of Matthew S. Murray as the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) administrator for the state of Missouri. Truman, future president of the United States, had gotten his own start in politics as a Jackson County judge, owing to his friendship and World War I service with Tom’s nephew, James M. Pendergast, usually known as “Jim” Pendergast. Murray’s appointment as WPA administrator for Missouri gave Pendergast control over as many as 80,000 jobs statewide, on top of tens of thousands of patronage jobs around Kansas City.

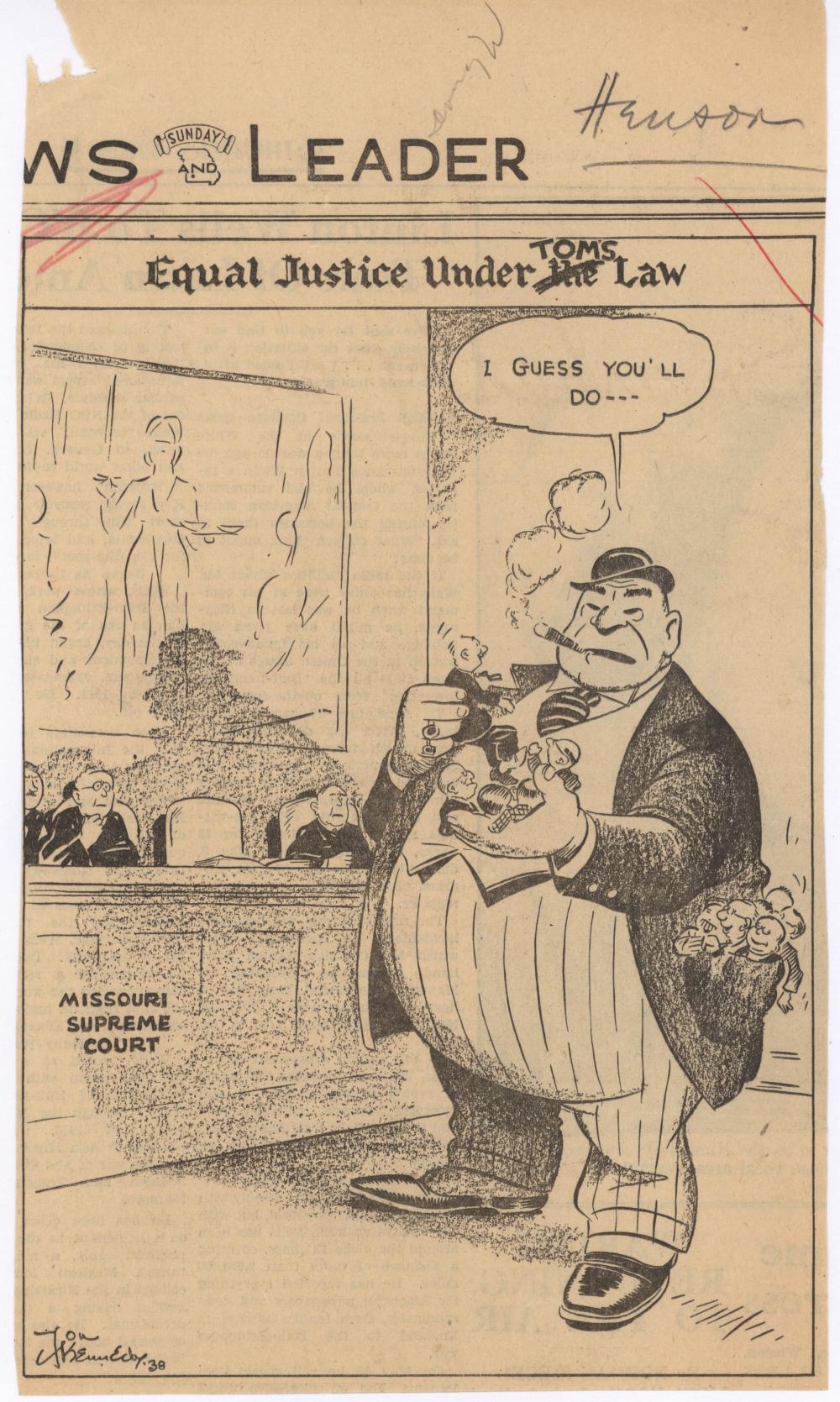

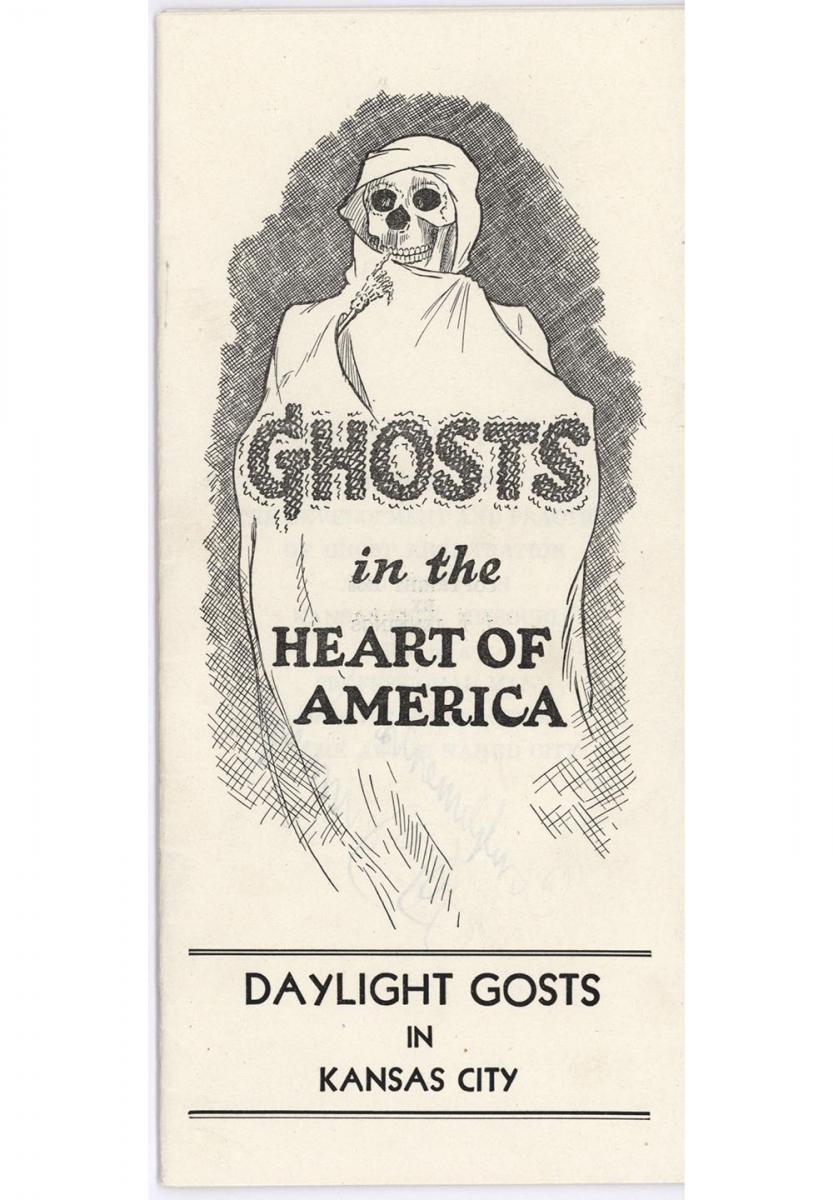

According to historians Lawrence H. Larsen and Nancy J. Hulston, the Pendergast machine reached its apex of electoral fraud in the election of November 1936 as it produced between 70,000 and 80,000 “ghost” votes. By 1936, Pendergast seems to have either felt invulnerable from prosecution or was losing control over the some of the more exuberant elements of his organization. He did feel compelled to publicly admit that some fraud had occurred, but he denied knowledge, responsibility, or involvement in any election activities due to his ill-health. He had indeed experienced a heart attack and was in overall declining health by 1936, and was thereafter incapable of climbing a set of stairs. In the Monroe Hotel, adjacent to his 1908 Main headquarters on the north side, an elevator was installed and a passageway created to connect the two buildings and allow him access to his office.

Considering Pendergast’s widespread influence and control over key government officials, imagining the fall of his organization may have been difficult for his supporters and critics alike. At the same time, his opponents grew in number over the course of the 1930s. Rabbi Samuel Mayerberg, of the Temple B’Nai Jehudah, was one of the earliest who was brave enough to publicly speak out against machine corruption in May 1932. Shortly thereafter, Mayerberg survived an attempt on his life, which only underscored the seriousness of his allegations. Criticism from civic groups like the Citizens’ League, Independent Voters League, and various women’s clubs continued to simmer and occasionally boil up. In the end, though, Tom Pendergast succumbed to a combination of overconfidence and the need for ever-larger infusions of cash to fuel his one insatiable vice (that is, outside of political corruption and smoking): betting on horse races. His fascination with horseracing ran so deep that, between 1928 and 1937, he helped established and operate, through affiliates, the Riverside Jockey Club in Riverside, Missouri, about six miles to the northwest of Kansas City. He was also purported to have installed an electrical wire allowing him to gamble remotely from 1908 Main. In just a few weeks between mid-August and mid-September of 1935, Pendergast’s addiction climaxed as he wagered over $2 million on horse races and netted a loss of $600,000.

As he accumulated gambling debts, Pendergast entered into a complicated insurance kickback scheme with insurance executives and the state insurance commissioner. The fallout from the kickbacks did not directly result in his arrest, but he failed to report the income to the IRS and pay taxes on it. On January 2, 1939, with a grand jury impaneled and U.S. Attorney Maurice Milligan investigating Pendergast machine activities, Pendergast’s bookkeeper, Edward L. Schneider, was found dead of an apparent suicide. Whether Schneider’s cause of death was suicide or murder is indeterminable, but he had already given Milligan enough information.

Boss Tom was soon to become inmate Tom. On April 7, 1939, Pendergast was indicted for tax evasion, and on May 29, 1939, he went to prison at the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth. He served 12 months of his 15-month sentence and was then released on a five-year parole, on condition that he would not have any involvement in politics for the duration of the parole. By then, though, he was socially ostracized and in no physical condition to make a comeback. He had suffered additional heart attacks since 1936, was mostly immobile, and had severe gastrointestinal issues. Completing his isolation, his wife Carolyn moved out sometime after his return home.

Tom Pendergast’s legacy, far from a simple story of 20th century American crime, has been remembered and evaluated in multiple ways. The period in which he predominated over city affairs is also remembered as a high point of Kansas City’s cultural vibrancy and national relevance. New institutions were established, including the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and University of Kansas City (now University of Missouri-Kansas City). The economy and population boomed in the 1920s, especially in relation to its peers, and thanks to his involvement in construction programs like the Ten-Year Plan, Kansas City and its people seemed to weather the Great Depression better than most other places. Much of the physical infrastructure built with Pendergast concrete (and taxpayer’s money) still stands today. Thanks to nonexistent local enforcement of Prohibition, Kansas City’s nightlife boomed; a famous style of jazz emerged. There is significant evidence that communities of racial minorities, whose members were important machine constituents, felt more fairly treated by the police and city governments than they did in the years before and immediately after Pendergast’s reign. For decades after Pendergast’s fall and until the revival of recent years, downtown Kansas City hollowed out to a neglected shell with few reminders of its former glory. Population growth stagnated. During those years, some undoubtedly longed for a return of the better aspects of Pendergast’s mixed legacy.

Of course, it must be remembered that even Pendergast’s achievements were fleeting. The illusion of miraculous city budgeting and governance, for example, shattered after it was revealed that embezzlement and freewheeling spending (which city manager Henry McElroy had quaintly brushed off as “country bookkeeping”) had resulted in more than $19 million in unreported debt. For most of his life, Pendergast’s wager that the public would tolerate corruption in exchange for other benefits had paid off—far better than he might have imagined in 1894 when he came to Kansas City to operate a saloon with his brother. But in the late 1930s, with his health failing and his gambling addiction mounting, the whole edifice crumbled. He died of heart failure on January 26, 1945, at the age of 72.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.