Jesse Clyde Nichols

- Date of Birth: August 23, 1880

- Place of Birth: Olathe, Kansas

- Claim to Fame: Kansas City real estate developer, city planner

- Spouse: Jessie Miller Nichols

- Also Known As: J.C. Nichols

- Date of Death: February 16, 1950

- Place of Death: Kansas City, Missouri

- Cause of Death: lung cancer

- Final Resting Place: Forest Hill Cemetery; Kansas City, Missouri

Jesse Clyde (“J.C.”) Nichols was a nationally renowned city planner in Kansas City from the first decade of the 20th century to the 1950s, whose legacy has come under intense scrutiny for his practices of racial redlining and segregation. Among his mixed legacies are several subdivisions in suburban Kansas City, the Country Club Plaza, and the national spread of deed restrictions and homeowner associations. A prudent businessman and widely considered an innovative visionary during his era, Nichols conceived of real estate development in economic terms. However, his means of maintaining stable property values in residential developments effectively segregated people of color from white Kansas Citians and have had long-lasting effects on the racial and ethnic distribution of metropolitan-area residents. Certain aspects of Nichols’s work continue to generate controversy: he carefully controlled nearly every dimension of his residential and commercial developments – from the building materials to the socioeconomic status and race of the residents who lived there.

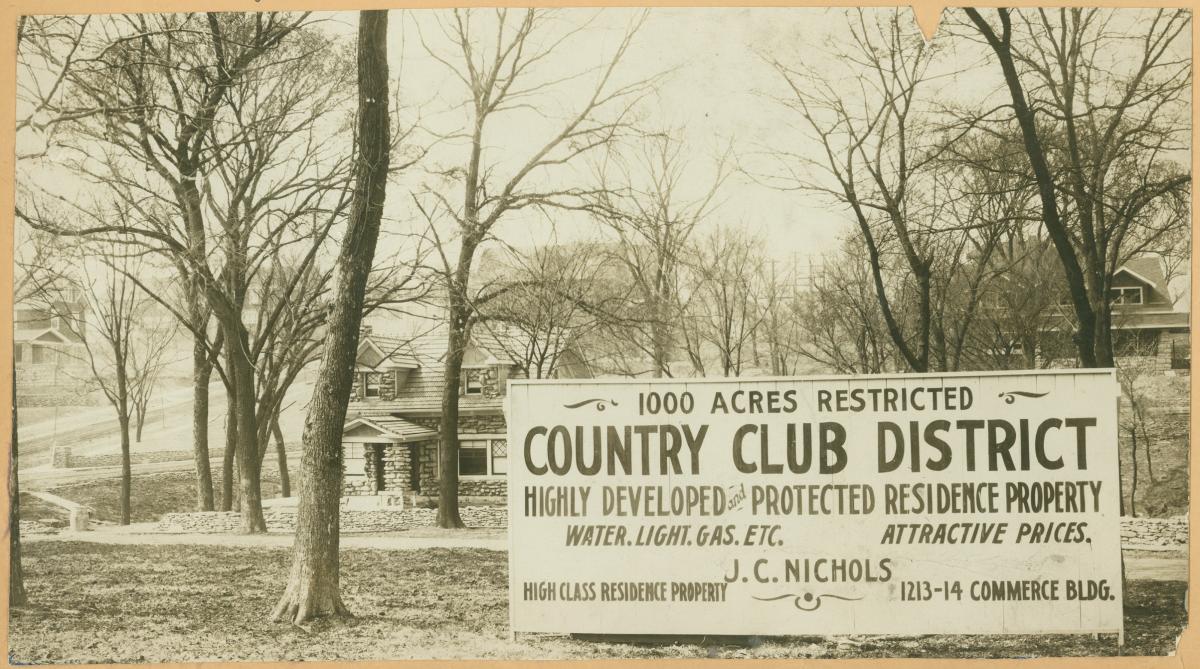

From a young age, J.C. Nichols demonstrated entrepreneurial acumen and a remarkable work ethic. He held multiple jobs and maintained an exemplary academic record throughout childhood and adolescence. After high school, Nichols began a meat-selling business and saved his earnings for a year to fund college tuition at the University of Kansas. His many jobs over the years also included a stint at the Kansas City Star as a correspondent. Following graduation from college and a year of study at Harvard University, he sold small homes around Kansas City. In 1905, operating with two friends-turned-partners as Reed, Nichols & Company, he began developing a 10-acre tract that he called the Country Club District. Only four years later, Nichols had enlarged the development to 1,000 acres.

Nichols’ chief professional interest was city planning and developing real estate in Kansas City. Between 1906 and 1953, he developed over 6,000 homes and 160 apartments, housing over 35,000 Kansas Citians. The Country Club District, intended for affluent Kansas Citians, was a cluster of subdivisions that Nichols developed from 1904 until his death in 1950. The neighborhood touted curbs, sidewalks, and wide roads that easily accommodated automobiles. Fountains and statuary dotted medians and esplanades. For Nichols, creating a picturesque suburban environment justified the expense of commissioning landscape architects to design an aesthetic of sophistication and exclusivity, as well as to maximize and maintain property values.

Nichols was also a prominent player in raising the nation’s only major monument dedicated to World War I, the Liberty Memorial. Beginning in 1919, he served as first-vice-chairman on the Committee of One Hundred—a group of local leaders and parents of veterans that formed to realize the project. The idea that the monument should commemorate liberty, rather than mourn the dead, was Nichols’s. He saw the project through to completion and urged the selection of the site opposite Union Station.

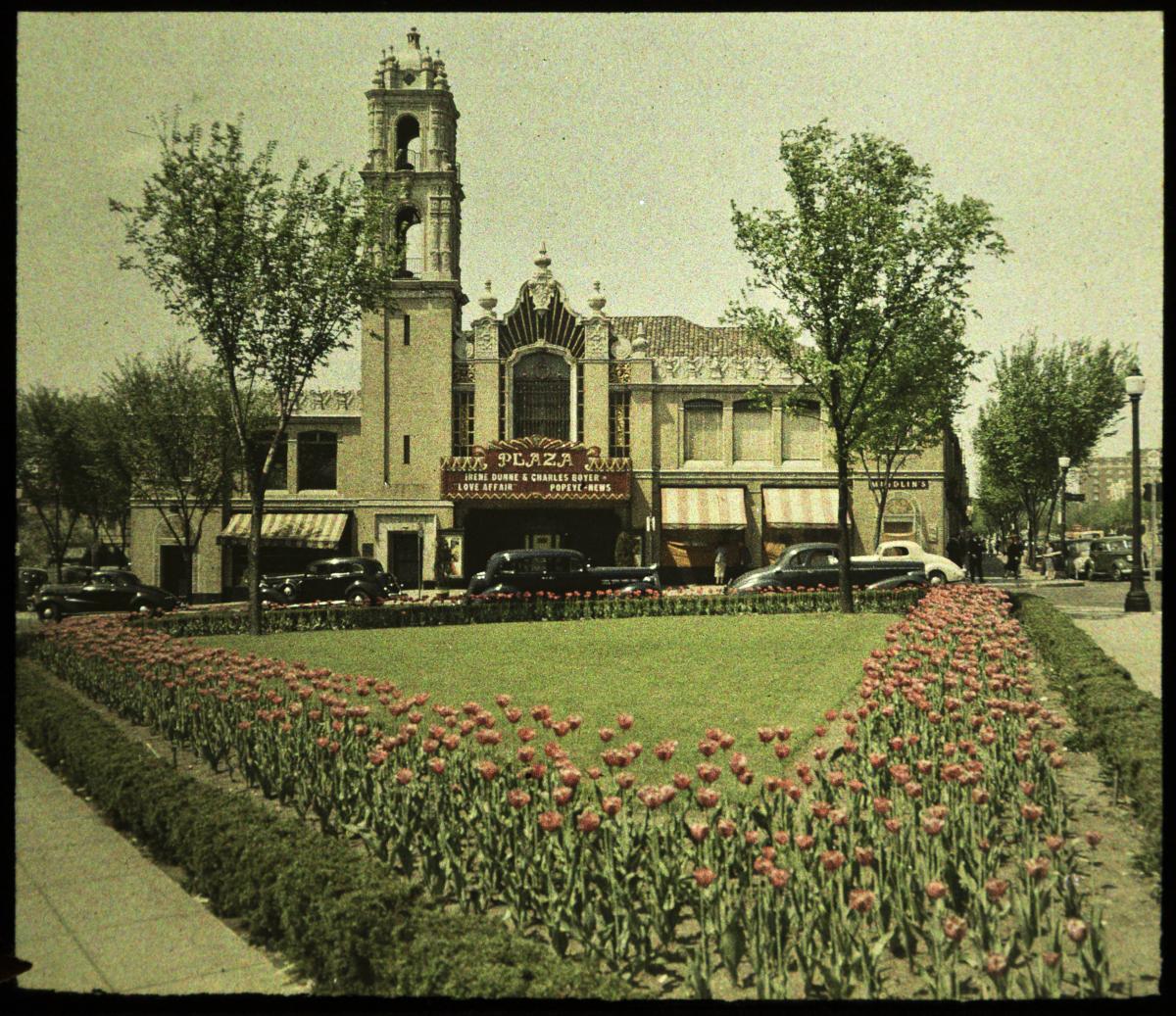

The Country Club Plaza, formally begun in 1922, was planned as a shopping center to cater to suburban Kansas Citians, especially by way of easy automobile access and ample parking. The Plaza was also closer in proximity to the middle and upper class subdivisions than were the downtown shops that were better accessed by streetcar. Nichols carefully regulated the design of each element, including roofs, wrought-iron fixtures, and façades. He stipulated building heights and cornice lines, emulating what he saw as an orderly and uniform effect of European city centers. The distinctive Moorish architectural style of Seville, Spain, seems to have been most influential for the city planner.

Above all, Nichols approached city planning and residential development from an economic perspective. The aesthetic, social, and legal components of his projects all converged to maximize property values, but often at considerable ethical cost. Just as Nichols selected each architectural and landscaping element of his subdivisions to reflect picturesque suburban ideals, he only sold properties to the type of resident that he believed suited his bucolic vision. Deed restrictions were legal contracts dictating factors such as building materials and minimum cost of home construction, but more significantly, forbade ownership by African Americans, Jews, and other minority groups. These legal contracts “ran” with the land and were among the tactics that ensured Nichols’s subdivisions remained exclusionary. Nichols marketed the deed restrictions, also called restrictive covenants, as measures to preserve property values, solidify community, and provide the high quality, exclusive residential environment promised to buyers.

Nichols viewed socioeconomic and racial homogeneity in his properties among the highest priorities for the ventures’ success. Deed restrictions actively perpetuated segregation within his subdivisions. These covenants renewed automatically from homeowner to homeowner and required an elaborate process to repeal; similarly, mandatory homeowners’ associations upheld Nichols’s vision by requiring community members to enforce such codes. Nichols did not invent deed restrictions or homeowners’ associations, but he popularized them as effective tools in city planning and applied these tactics to large, contiguous swaths of Kansas City. By the 1940s, mandatory homeowners’ associations were common throughout the United States.

Nichols was thoroughly engaged in various local and national organizations, such as the National Association for Real Estate Boards, National Association of Home Builders, and the Committee of One Hundred. Nichols never held political office, but his residential developments were the first choice for local civic leaders. Both city manager Henry F. McElroy and Democratic boss Tom Pendergast owned homes in the Country Club District, and Pendergast later owned a mansion on Ward Parkway that was designed by the Nichols Company.

The J.C. Nichols Company was among the first and highest profile organizations to encourage the use of racially restrictive covenants, which ultimately influenced racial population patterns nationally. Nichols was also instrumental in the emerging system of urban planning and regulation of private and use that is central to today’s real estate industry. The scope of Nichols’s influence on Kansas City, and city planning nationally, would be difficult to overstate. His belief that residential developments should be regulated for cost efficiency, transportation accessibility, and stability has endured long after his death.

This essay was developed as part of an Applied Humanities Summer Fellowship, cosponsored by the Hall Center for the Humanities at the University of Kansas.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.